What is bitterly disappointing for any England fan is that the roof caving in on Saracens will have serious ramifications for the English game, at both international and club level.

The decision announced on Saturday evening by PRL to relegate the double-winning European and English champions for salary cap infractions carries with it the likelihood of their squad being disbanded, with many of their international stars scattered around England, Europe – and perhaps even further afield – on loan deals.

The suggestion is that Saracens are £2m above the cap for the current season, and a hardening of attitudes among other Premiership club owners/chairmen this week prompted PRL to bring forward the relegation announcement which was expected tomorrow.

This will turn the remainder of the Premiership season into a semi-competitive procession, because the clubs will no longer have the incentive to play for their places in the league.

It will put the future of Saracens – who provided nine players to England’s 2019 World Cup squad, and five to the 2017 Lions – England captain Owen Farrell and Test stars Maro Itoje, Jamie George, Mako Vunipola and George Kruis – in serious jeopardy.

The prospect of playing on Championship grounds next season could push other England internationals as well as their talented academy players, to move elsewhere.

There is no denying the defending European champions have contributed mightily to the parlous state they now find themselves in by being ‘reckless’ in their cap transgressions.

However, what should also be remembered is that the salary cap system is deeply flawed.

Saracens have already paid a huge price for their three seasons of misdemeanours with a £5.36m fine when the salary cap disciplinary panel convened by PRL, and headed by Lord Dyson, handed down its ruling in the middle of November.

Their aggrieved rival Premiership clubs have had a pound of flesh, with the fine being divided between them, giving each almost £500,000.

The waters have been muddied by the refusal of the shadowy Premiership Rugby Investor Group, comprised of the owners and chairmen of the other 11 Premiership clubs, to make public Dyson’s ruling.

Instead, they chose to keep most of the detail out of the public domain by publishing a skeleton summary of barely 150 words. With the issue kept private, grievances on both sides were allowed to fester.

The timeline is significant because Saracens were disputing that their co-investments were pushing them above the cap until the November ruling. By that time, the Saracens player contracts for this 2019-20 salary cap season, which runs from July to June, were already in place – but, pressure for the club to prove they were within the £7m cap this season, understandably started to mount immediately after the Dyson ruling.

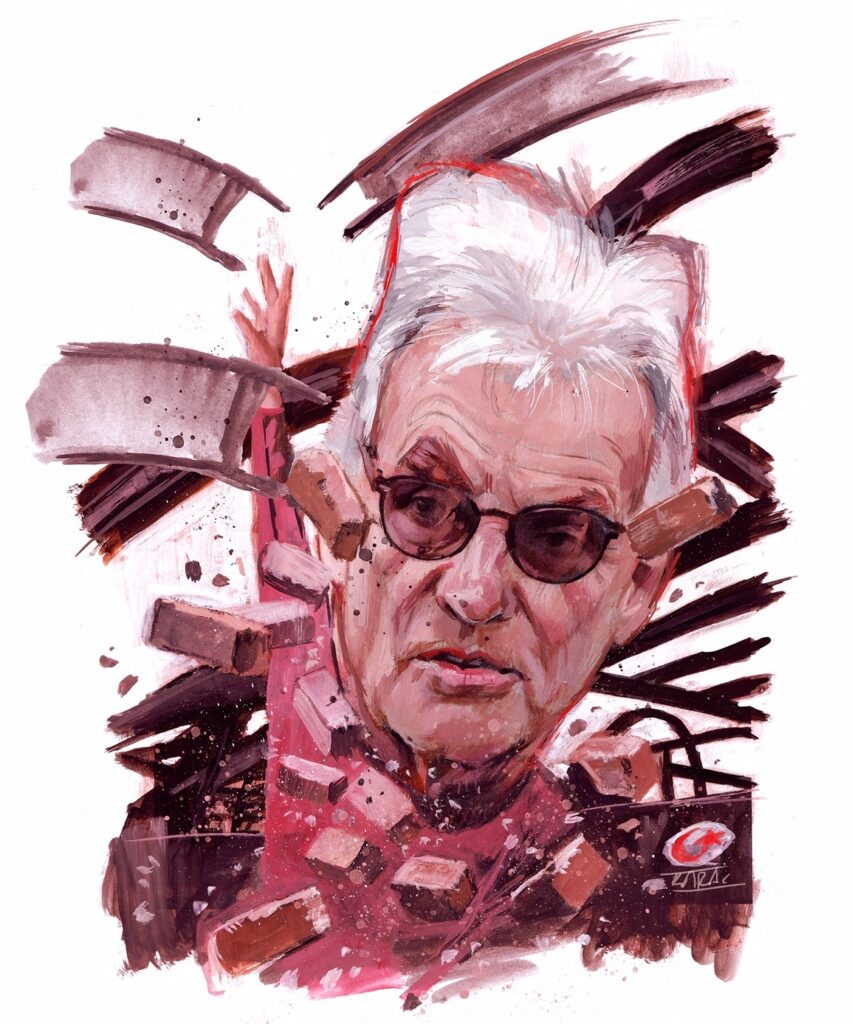

It intensified when Saracens owner Nigel Wray, having refused to appeal against the ruling, bowed to Investor Group pressure to resign as chairman, transferred his shareholding to members of his family, and brought back Ed Griffiths as chief executive.

The controversial Griffiths had been implicated in a salary cap dispute in 2015, when Saracens and two other Premiership clubs were accused of breaching the voluntary agreement.

This 2015 furore led to a collective decision by the Investor Group to make the salary cap a more binding agreement with much more stringent sanctions.

What has resulted is an increasingly acrimonious dispute with some clubs taking umbrage at Saracens still seeing the £7m cap as an elastic guideline rather than a red line.

This is a sorry tale of mutual exasperation and antagonism, and deep-rooted administrative failings on the part of both PRL and Saracens.

Insiders close to the Premiership clubs Investor Group are incensed because, as one told me, “Saracens have fought and fought, wriggled and wriggled, to block the investigation of the current squad.”

There is also anger at the lack of contrition from Saracens, and a strong sense that the return of Griffiths is deeply contentious. A leading Premiership club figure described his reappointment as “like sticking pins in people’s eyes”.

Griffiths must make a £2m squad salary cut for Saracens to be compliant. Not only do many rival clubs have no more spending room under the cap, but the compensation Saracens pay to any player released is added to the salary cap they are already breaching.

Saracens feel they are victims of an inadequate cap system. Wray, whose co-investments with leading players have a significant element of providing them with business opportunities after rugby, has often voiced his strong opposition to a cap allowance which penalises clubs producing international players.

He has pointed out the serious shortcomings of a Premiership ‘smoothing’ mechanism whereby Saracens – who have more international call-ups than any other Premiership club – get only £80,000 of the £180,000 compensation agreed with the RFU for each England player.

If Saracens got the remaining £100,000 each for the seven to ten players they release regularly for international duty, it would have more than covered the £650,000 breach of the cap they were initially found guilty of for 2016-17 and 2017-18.

My instinct is that the action taken by the Investor Group against Saracens is at the extremity where justice ceases to be served because the punishment is so severe it bears no relation to the crime.

Saracens are guilty of significant salary cap transgressions, and they have paid a financial penalty which would have sent some of their Premiership rivals under.

To keep punishing Saracens, especially when the salary cap system is badly deficient, appears vindictive and self-serving.

Instead of relegation they should have have been given a clear deadline two months ago, which ought to have been in the public domain rather than hidden from view, in which to make cuts.

The Premiership clubs should be careful what they wish for, because the collapse of England’s most illustrious club could leave wreckage strewn across the country’s rugby landscape for years to come.

It might also leave them facing a charge in the court of public opinion of administrative vandalism.

Latest News

Super Rugby Americas: Round Ten Review

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions: Biggest winners and losers from Andy Farrell’s selection

You must be logged in to post a comment Login