There was a time, believe it or not, when Wales pioneered the science of coaching on a global scale, when the world beat a path to Cardiff Arms Park. There they listened to the gospel preached by a former schoolteacher who claimed to be the amateur game’s first professional coach, the late Ray Williams.

His manual, based on cutting-edge philosophies and new-fangled concepts like ‘squad systems’, so impressed Bob Templeton that the famous Wallaby returned to Australia as Williams’ ‘disciple Down Under.’

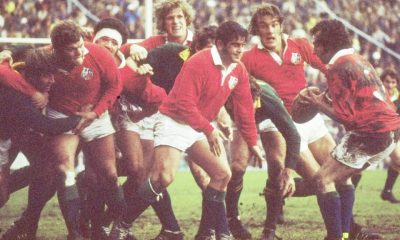

Back then, in the early Seventies, Wales were ahead of the game. As well as the first full-time ‘coaching organiser’ in Williams, they also had the first amateur coach to be accorded superstar status for inspiring the Lions to their first, and only, series win in New Zealand, Carwyn James.

Welsh coaching and coaches were all the rage. Now they seem to be disappearing faster than the yellow-legged mountain frog, an endangered species once found in abundance on higher ground in Nevada and California.

Thirteen seasons ago, Welsh coaches were still holding their own, especially at home where Dai Young (Cardiff Blues), Paul Turner (Newport Gwent Dragons), Lyn Jones (Ospreys) and Phil Davies (Scarlets) ran the regional quartet.

That Welshmen should be in charge of Welsh teams was still taken for granted, if not for much longer. Gareth Jenkins had been put in charge of the national team, his appointment restoring faith in the Welsh way of doing things after the Graham Henry-Steve Hansen years.

Kevin Bowring, the last home-grown Wales coach pre-Henry, had long been installed at Twickenham as the RFU’s elite coach over a period when England won the World Cup. His dismissal after the WRU ignored his detailed plan for overdue structural change had left him ‘feeling a bit of an outcast, as if I’d lost some of my Welshness’.

Elsewhere in England, one head coach flew the Welsh flag in the Premiership on his Kingsley Jones, with some success at Sale. In Scotland at the same time, another graduate from the valleys’ school of coaching, Lyn Howells from Pontypridd, headed operations at Edinburgh. Now the number of Welshmen employed across Europe’s three major leagues as director of rugby or head coach can be counted not just on one hand but one finger. Young is the only one, one out of 40.

The English Premiership still has a few clubs in English hands even if Newcastle‘s relegation under Dean Richards means they are down to four: Rob Baxter at Exeter, Steve Diamond (Sale), Paul Gustard (Harlequins) and Stuart Hooper (Bath).

Irish coaches outnumber the Welsh variety five-to-one: Leo Cullen at Leinster, Jeremy Davidson at Brive, Geordan Murphy at Leicester, Declan Kidney at London Irish and, most decorated of all, Mark McCall at Saracens. It had been six until Allen Clarke paid the inevitable price for losing a few too many games and duly parted company from the Ospreys.

A victim of outrageous odds made all the more so by the folly of starting the Champions Cup without the World Cup cast, the Ulsterman had been gone for almost three days before his employers got round to addressing the subject. Even then it was more of a mumble than a statement in which they told supporters nothing and said they would ‘appreciate your patience’.

Long after Clarke had made his exit from the Liberty, Ospreys’ website carried a lengthy piece from their ex-head coach penned before the 44-3 hammering at Saracens, an all too predictable result for a team woefully underpowered with too many recovering from their Japanese exertions or injuries.

Clarke spoke of a striking image in his office of men mining for coal, a photograph, he said, which ‘symbolised the values that are inherent to the Ospreys and myself…a group of men working in life-threatening conditions, relying on each other, showing what teamwork is..’

He went on : “I have developed a real understanding for the history of the area and how important mining was and still is to the community. It reminds me of the world-famous photograph of men having lunch sitting on a girder during the building of the Rockefeller Centre in New York which Sir Alex Ferguson had hanging on his office wall.

“Sir Alex said the photograph inspired him. The message I was trying to get over to the players was that however hard they think things are for us now, they are nothing compared to what miners dealt with every day of their working life.”

Five days after his premature departure barely halfway through a three-year contract, the Ospreys’ website were still trying to give the impression that he was still around, hence their feature entitled ‘Catch up with Clarkie’.

The protracted lack of an official comment inevitably spawned renewed rumours over the region’s very existence following last winter’s proposed merger with the neighbouring Scarlets. Rob Davies rode to the rescue to keep the club going just as he had kept Swansea City going all those years ago but there has to be limit even to his largesse.

PETER JACKSON

United Rugby Championship

Vaea Fifita’s commanding presence has Scarlets pushing for URC play-off spot

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions Watch: Caelan Doris confirmed to miss the tour with injury

You must be logged in to post a comment Login