Just before the collision it is essential that you do not shut your eyes for a moment so as not to miss the target. Many have crashed into targets with wide open eyes. They will tell you what fun they had – Albert Axell: Kamikaze.

The words sound like the introduction to a crash-course in how to tackle a larger opponent and revel in the delight of bringing him to his knees. Instead they come straight out of the instruction manual for the deadliest pilots of the Japanese Imperial Air Force of the Second World War, the tokkah-tai-in.

The man who did more than any other to bring the World Cup to Japan would have known those words off by heart and the final exhortation for the glory of Emperor Hirohito:

“Remember when diving into the enemy to shout at the top of your lungs: ‘Hissatsu!’ (Sink without fail). At that moment, all the cherry blossoms at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo will smile brightly at you.”

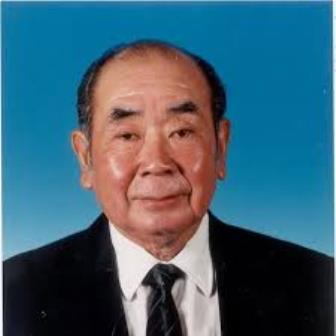

Shigeru ‘Shiggy’ Konno’s self-deprecation description of his wartime role never changed: “I was a failed kamikaze pilot.”

Had he been a successful one, his name would have been enshrined along with more than a thousand contemporaries at the Chiran Peace Museum in the naval port of Kagoshima.

Instead rugby on a global scale will honour his memory at a ceremony here in Tokyo on November 3, his posthumous induction into the Hall of Fame, the sport’s holy of holies, ensuring a memorial far removed from the one the young Shiggy craved during the final months of the war in the Pacific.

“The only reason I am still alive and talking to you today is that I wasn’t a very good pilot,” he said at a hotel in Swansea during the early stages of Japan’s breakthrough UK tour more than 40 years ago. “That’s why my mission was to be the very last.

“Everyone has to fight for his country and I kept asking the commanding officers: ‘Why do you keep sending pilots who are married? Why not send me, a single man?’

“The answer was always the same: ‘We valued our planes more than your ability to hit the target’. So my mission was put back until the first week of September 1945. Fortunately for me, the war ended in August.”

The atom bombs the Americans dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki led to Japan’s surrender at a terrible price. The loss of an estimated 200,000 lives saved Konno’s by sparing him the most fatal of appointments at the controls of a flying bomb.

Post-war he devoted his unflagging energy and leadership skills in pursuit of a more rewarding dream which many of his compatriots dismissed as a lost cause.

One day Shiggy would make Japan a rugby power, playing the game in the grand manner in constant defiance of physical handicaps.

At Twickenham in 1973, for example, his Japan team made a real impression with the pace of their running and the precision of their passing, all achieved despite a pack of lightweights averaging twelve-and-a-half stone a man.

A cultured man of unfailing courtesy who spoke immaculate English, he filled every role with distinction over a period of four decades, as coach, manager, chairman and president. As a long-serving member of the International Rugby Board, the forerunner to World Rugby, he found a global platform for the promotion not just of his country but the whole of Asia.

A true-blue amateur, Konno was realistic enough to accept the inevitability of professionalism.

“Like a lot of us, he kept his finger in the dyke of amateurism for as long as possible,” says Scotland’s former international referee Alan Hosie, a fellow IRB member. “But he knew it was only a matter of time.

“He was a wonderful character. Sometimes at board meetings, he would give the impression of being asleep which was an illusion. You realised very quickly that Shiggy knew about everything and knew everyone.

“His contribution went beyond the game. The fact that the Queen awarded him an OBE in 1985 said everything about what he did for relations between Britain and Japan. And the World Cup has turned out to be a huge commercial success.”

Konno died at the age of 84 in April 2007, some two years before Japan cashed in on his monumental creation by winning the right to host the tournament.

How he would have loved to have seen the earth-shattering victory over the Springboks in Brighton four years ago and the electrifying manner of Japan’s more recent conquest of Ireland.

The size deficiency has been addressed by the advent of a forward quartet from far beyond the Land of the Rising Sun – New Zealanders Luke Thompson and Michael Leitch, the South African Pieter ‘Lappies’ Labuschagne and James Moore, a Queenslander from Brisbane.

International Rugby

Henry Slade pulls out of England’s tour of Argentina and the USA through injury

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions told: Beware Australian dirty tricks

International Rugby

George Ford joins 100 club in England victory over Argentina

You must be logged in to post a comment Login