ENGLAND and Australia can both raise their bats at Twickenham on Saturday when they bring up the half century and play each other for the 50th time at Test level, a sporting rivalry that operates within a generally good natured, locking of horns between the two nations.

England, and this surprised me, have played the Aussies more than any team outside of Europe – they’ve met the Kiwis on 41 occasions and the Boks 42. Although very close statistically – the Aussies lead 25-23 with one draw – over the decades it’s been a contest dominated by first one team and then the other. Just when it starts getting a little predictable the tide tends to turn dramatically.

England are currently on a run of five straight wins since their traumatic World Cup defeat in 2015 and have won seven of the last eight since 2012, while between 1982 and 2000 England won just two of their 13 fixtures. England didn’t win on Australia soil until June 2003 when they went with the cold, premediated aim of breaking that depressing run before RWC2003.

“Any Aussie will tell you that New Zealand is THE game for the Wallabies but England always ranks a strong second behind that Bledisloe Cup rivalry,” says Michael Lynagh who enjoyed six wins in eight appearances against England. “We have been playing each other for a long time now and its always been very competitive.

“Put it this way, the defeat against Wales recently will hurt for a short while but believe me it will be quickly forgotten if Australia could nick a win on Saturday.

“And that’s why you would never count Australia out even if in all honesty they looked a bit stale in Cardiff and in need of a rest. They were struggling to get into fourth gear against Wales, let alone fifth, but everybody in the squad know how a win over England at Twickenham plays out back home and the motivation levels will rise accordingly.”

Lynagh adds: “While we are on this subject can I make one plea before this week’s match? Can the sporting world stop calling any clash between Australia and England, in any sport, the Ashes. The Ashes belongs totally to the cricketing world, it’s totally unique to them, and the rest of us need to stop gate-crashing that.”

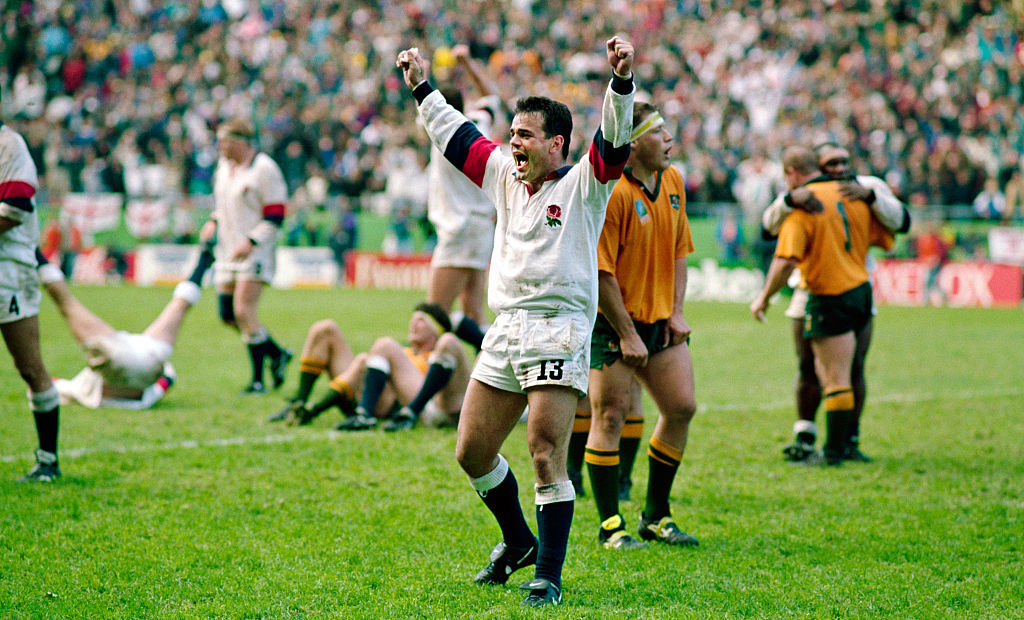

Champion: Michael Lynagh kicked Australia to World Cup glory in 1991 (photo: PA Images)

Historically the Aussies, on their 1908-9 tour, were the last superpower Southern Hemisphere nation to visit these shores with both the New Zealand Natives (Maori) and the All Blacks making the trip long before them while the Springboks had arrived in full force in 1906. Mind you, the Australians made an immediate impact beating England at Blackheath and taking the first Olympic gold medal when they defeated Cornwall at the White City Stadium.

Rugby moved slowly in those days and the teams met only three times in the next 49 years – there were two world wars to contend with during that period.

Initially it was a fixture of memorable moments rather than great games. Peter Jackson scored a remarkable try in the Twickenham mud in 1958 but how many of you can remember the score? The Battle of Ballymore in 1975 was brutal and bloody but again what was the score line that day? Erica Rowe made the front page with her half-time streak in 1982 but the rugby made little or no impression.

It was the World Cup that finally brought out the best in the simmering rivalry, starting in 1987 when England produced their best performance in an otherwise disappointing campaign when losing 19-6 in Sydney, an Aussie win that included one of the dodgiest tries of all time from David Campese with a knock-on you could see in Row Z.

By 1991 England were flexing their muscles and putting plenty of stick about and with their streetwise pack to the fore they reached the final against an all-court Aussie side who had seen off favourites New Zealand in the semi-final. At which point the debate starts. Why did England start flinging the ball about with abandon in the first half of the final? And did it cost them the game?

“Plenty has been written about our so-called change of tactics for the final so here’s my version,” says Will Carling. “We had toured Australia in the summer, lost 40-15, and basically our pack got hammered up front and they also produced a better kicking game on the day and we had meetings about this a couple of times in the week and discussed tactics. It was decided we had to open up a bit, try and stretch Australia, and this notion that we just woke up on Saturday morning and decided to change tactics is a complete nonsense.

“Two things worked against us on the day. We did try and put tempo into the game and we had the players – but we were inaccurate and didn’t make the final pass tell. The tactics didn’t quite come off. If we made a mistake at all it was not to realise that our pack had progressed since the summer and were now shaping up against the Australians better. We might have tweaked our tactics on the hoof but bottom line it made no difference. They were better than us.

“Australia weren’t at more than 80 per cent and they still beat us fair and square. I have no issues whatsoever with their win and no real regrets about the 1991 World Cup, not like I did from 1995 when I felt we were a much better side than what we actually put out there on the field.”

Lynagh concurs: “Before the game we thought England would probably use their forward power to try and control the game but we kept an open mind so when they produced a Plan B and started running and moving the ball it wasn’t a shock. We just battened down the hatches and defended like we had done against New Zealand. The surprise was possibly that England didn’t revert to Plan A a bit quicker!”

Just four years later England had their revenge with a late Rob Andrew dropped goal clinching a notable quarter-final win in Cape Town although, as Carling alludes to, the joy of that victory was short-lived with a right royal thrashing by New Zealand at the same venue a week later.

Redemption: Will Carling celebrates beating knocking out reigning champions Australia in the quarter-finals of the 1995 Rugby World Cup (photo: David Rogers/Allsport/Getty Images)

The ultimate revenge, however, came in 2003 with that World Cup win in Australia against the Wallabies and there was also a huge feelgood factor to England’s unexpected quarter-final win in Marseilles in 2007 when the England forwards and the front row in particular crushed the life out of their opponents.

Much of that though is countered by the excellence of the Australians 33-13 Pool win in 2015, one of the most depressing moments in modern day English rugby history. It felt like England had been knocked out of their own World Cup without firing a shot.

It also a featured a commanding performance from Bernard Foley at ten and it has been a surprise to see his starting place called into question this season. Elsewhere there is much to chew on. Matches against Australia marked both the start of Clive Woodward’s reign – a 15-15 draw at Twickenham – and the end, a 51-15 shellacking at Brisbane in 2004 with England out on their feet after too much rugby and, yes, maybe a little too much post-World Cup partying.

In fact matches against Australia generally were huge for Woodward. On the tour from hell in 1998 it was that record breaking 76-0 win in Brisbane which demonstrated just how far a weakened England were off the pace although, at the same time, a couple of gems for the future were unearthed.

There were two more defeats against the Aussies after that all-time low point before England got on a five-match winning run culminating with the World Cup win although Woodward himself always believes their 25-14 win in Melbourne a few months earlier was their best performance.

In more recent times the English highlights have been Chris Ashton’s wonder try at Twickenham in 2010, with assists from Ben Youngs and Courtney Lawes, and that remarkable 3-0 series win two years ago which signalled England were back after the disappointment of RWC2015.

BRENDAN GALLAGHER

English Championship

What the new Championship format could mean for English rugby

You must be logged in to post a comment Login