By Peter Jackson

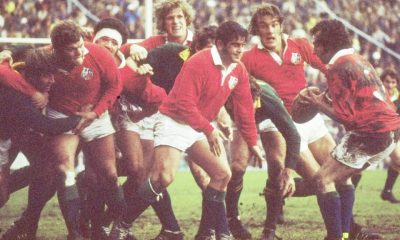

Even now, more than 20 years after his death, Clem Thomas remains as central a figure as ever in the one-sided saga of Wales and New Zealand. Seven decades after unleashing a cross-kick on its 50-yard trajectory into the arms of the Olympic sprinter Ken Jones, one of the game’s great adventurers would be hard pushed to believe that Wales have still not beaten them since that last Saturday before Christmas in the Coronation year of 1953.

Twelve American presidents have sat in the Oval Office since then compared to 13 British Prime Ministers in Downing Street with a fair bet that both numbers will keep rising before Wales get round to ending their run of 29 defeats in 29 attempts.

They managed it 64 years ago despite amateur regulations prohibiting them from assembling before the Friday afternoon. After an hour or so, the players then retreated to their homes scattered across South Wales by road and rail only to reassemble back in Cardiff for lunch at noon the next day.

It saved the WRU money although they acted swiftly to pre-empt any misconceptions of a Scrooge mentality by letting it be known that the players preferred to sleep in their own beds. Thomas would not have slept well in his, at all.

He arrived back at the family farm in Brynamman in an understandably distraught state over a fatal accident on the drive home from the West Country. A woman cyclist was killed and while the police cleared Thomas of any blame, the selectors understandably wondered whether he would be in the right frame of mind.

The chronicle of events behind the tragedy has been told for the first time in Clem, a biography written by his eldest son Chris and newly-published by Iponymous. “Dad never ever spoke to me about it,” Chris tells me. “When he got home that night, Bill Ramsey, then the treasurer of the RFU, rang him and offered to intercede with the WRU on his behalf. They had a good chat and Ramsey told the Welsh selectors: ‘Don’t be so bloody stupid to think about leaving him out. He’s fine.’

“My grandfather sorted it out. He sat Clem down, gave him a couple of strong cups of tea and said: ‘You’ve got to play. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. It won’t come again.’

“It really was because in those days the All Blacks used to come here once every ten years, if you were lucky. He never bragged about the cross-kick. Whenever the subject came on, he always dealt with it in a very self-deprecating way.”

Hemmed in close to the left touchline, Thomas had used the cross-kick to stunning effect in Wales’ last game of the previous Five Nations, the ploy providing the try for centre Gareth Griffiths which did for France at Stade Colombes.

With the All Blacks’ match heading towards an honourable draw at 8-8, Thomas had time to raise the ball aloft in one hand in what some saw as a dummy to Bleddyn Williams, hobbling around after damaging a thigh muscle.

The Kiwis clearly did not interpret it as a theatrical declaration of intent. They were caught so hopelessly flat-footed that when the ball dropped beyond the far upright it bounced perfectly for the zooming Jones to take it at full-throttle and win the game.

A wing forward whose English public school accent belied a handiness to look after himself in the toughest company, Thomas had thereby completed a double along with the Swansea prop ‘Stoker’ Williams without precedent in the British game.

The previous Saturday both had played in the All Whites’ 6-6 draw against the All Blacks. It ended with the irascible Thomas and New Zealand’s full-back Bob Scott scrapping their way towards the tunnel at the St. Helen’s ground.

“There was some bad blood between them,” Chris recalls. “Dad was accused of rabbit-punching Scott on the back of the head. It ended with another of the Swansea back row, Len Blyth, almost literally kicking Clem down the tunnel to get him out of any more trouble.”

Peter Robbins, the England back row forward and a contemporary of Thomas’ at Cambridge University, seized on the family’s butchery business to draw the most telling metaphor of Clem the careering flanker, describing him as ‘the only man I knew who was allowed to practice his trade on the pitch’.

A Test Lion in his own right, Thomas also drove in the Monte Carlo rally, won a downhill race on the piste at St. Moritz and while no doubt on a different sort of piste, once attempted to swim across the Seine at four in the morning.

He owned racehorses, twice stood as an unsuccessful Liberal candidate for Welsh constituencies before reinventing himself as a well-informed journalist for the Observer and Guardian only to die suddenly in 1996 at the age of 67.

As a boy growing up not far from the family farm, Gareth Edwards remembers bumping into him and noticing that he had used his Barbarians‘ tie to hold up his trousers. “Clem kicked down the doors that so many people felt were closed to them,” Edwards says in the foreword to the book. “Then he’d march through confidently and meet the world head-on.”

After 64 years of trying to knock the New Zealand door down, Wales will try again this Saturday.

United Rugby Championship

Vaea Fifita’s commanding presence has Scarlets pushing for URC play-off spot

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions Watch: Caelan Doris confirmed to miss the tour with injury

You must be logged in to post a comment Login