By Brendan Gallagher

RUGBY can be a game of inches in so many senses, not least 50 years ago today when Danny Hearn moved in to tackle burly New Zealand centre Ian McRae at Welford Road. As play moved on Hearn lay eerily motionless, his life forever changed.

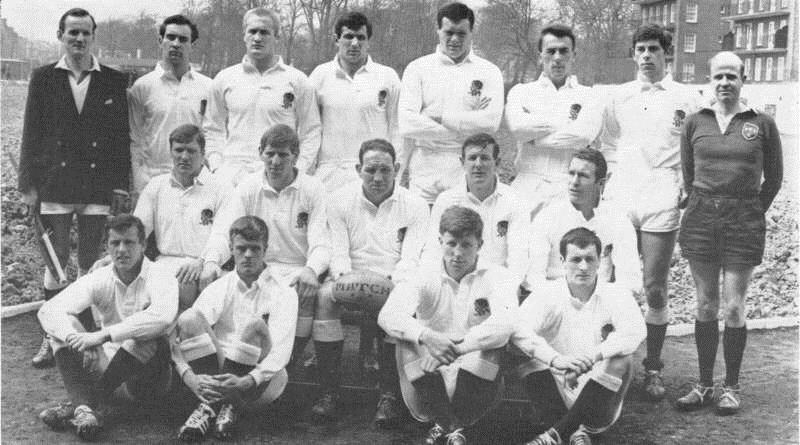

Hearn was playing for the Midlands & Home Counties and after the game the England selectors were to announce the England team to play the All Blacks the following Saturday. McRae was famed for his crash ball runs – he was one of the earliest and best exponents of the tactic – and despite his slender build Hearn was considered the most tenacious and fearless tackler in the English game. Their tête-à-tête was going to be pivotal to the match and after just four minutes came their first ‘clash’.

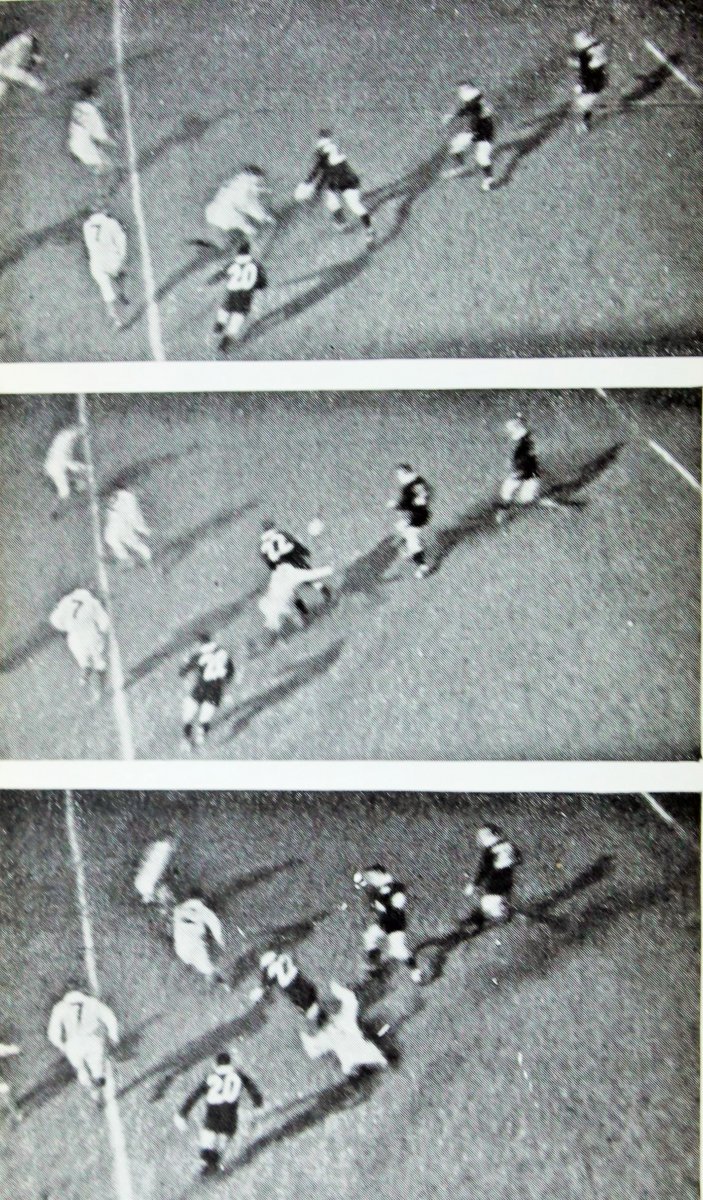

When you look at the tape and stills it was perhaps three inches away from being the perfect tackle, this was no reckless adrenalin-fuelled challenge. McCrae, as expected, charged hard but Hearn lay in wait and tracked him from the left, looking to pin his opponent with a fierce low tackle from the side, not front on.

The Bedford centre chose his moment carefully but misjudged his approach by a fraction. Instead of getting his head behind McRae’s backside as he wrapped his arms around the Kiwi, he hit McRae’s hip bone full on.

Another couple of inches to the right and his head would have hit McRae’s rump and slid safely round to the back. Instead the impact of the collision broke Hearn’s neck and in an instant dramatically changed the course of his life.

Hearn’s injury – seen live on TV and much discussed in the media for months after – left him a quadriplegic and was one of the first such injuries to enter the consciousness of the general sporting public. His remarkable recovery – or at least his uncanny ability to adapt and cope – was also an inspiration for those enduring the same fate, but at the same time his travails put into sharp perspective how ill prepared Britain was as a nation to help those suffering such catastrophic injuries.

Hearn was both thankful and extremely critical of Stoke Mandeville where he spent ten months at the start of his rehabilitation process. The low point, as he recalled in his book Crash Tackle was every Wednesday which he termed Circus Day, when all the inmates at the zoo had to perform in front of a host of doctors and experts assessing their degree of paralysis and recovery. Crude stuff, embarrassing, confidence sapping, heartbreaking. Happily the landscape has changed considerably with the medical authorities realising that empathy as well as discipline is required and Hearn was a key figure in that, although he waves away such suggestions.

Life-changing: Danny Hearn pictured at Stoke Mandeville Hospital where he learned to walk with the assistance of crutches

Fifty years on Hearn is living in contented retirement in Skibbereen in glorious Bantry Bay, cared for mainly by his devoted wife Jean. After retiring as a teacher at Haileybury in 2000 he moved to Ireland where he had inherited a small property from his grandmother. He is half Irish anyway – one grandfather was the Bishop of Cork – and back in the day he once received invitations to play in both the Ireland and England finals trials in the same week. It was an agonising choice and although he opted for England there is a strong hint of the sharp witted and pugnacious Celt about Hearn.

Life is good and fulfilled. He can just about walk the 20 yards or so to his car outside and when the weather is fine he and Jean enthusiastically explore the endless beauty of West Cork. On other days he will enjoy a bit of craic with Tom Kiernan and other Munster luminaries while he is fascinated and transfixed with Skibbereen’s local heroes, the O’Donovan brothers – Paul and Gary – the current world double sculls rowing champions.

On a fine day he will watch the lads put in the hard yards out in the Bay and is transported again into the world of elite competitive sport. “The O’Donovans are the greatest sports story I have ever witnessed. They have nothing compared with others, their boathouse is a shack, yet they take on the world and have done it all themselves. Don’t write about me, write about them.”

Hearn is always upbeat, it’s his default setting, but don’t be deceived. He needs constant assistance and care – don’t go thinking disabilities like his just fade with age – and, at 77, there are potentially other health issues as well.

“I’ve been very lucky and count my blessings, but without wishing to sound like a martyr, it’s still bloody hard work. You are always walking uphill into the wind so to speak. The effort is takes to live rather than exist never eases. When you go past 70 there is going to be a steady decline anyway whether you are coping with a disability or not. I am very conscious of having days when my energy is waning. That’s when I need to push myself even harder.

“I’m still very reliant on Jean from the moment she gets me up in the morning to when we go to bed. She is now 73 which of course makes it more difficult for her as well. We get some help in most days to lessen the load just a little. Jean badly needs a break as well occasionally, even if it’s just for a couple of hours.

“Aside from Jean’s devotion and the support of many wonderful friends avoiding serious illness has been my biggest stroke off fortune. Touch wood. To be seriously ill with flu, an infection or God forbid something worse on top of a serious disability, must be very stressful and draining. You must be vigilant and almost obsessive about your general health. You must keep on top of things.

“I am lucky in that I have always had a positive approach to life. Straight after the injury the doctors at Stoke Mandeville never speculated on the severity of my injuries and it never occurred to me that I wouldn’t recover – which looking back was a good thing. It’s possibly just as well I wasn’t made aware of the full prognosis.

“I was still full of thoughts of making a full recovery, even playing sport again, continuing where I left off and it was quite a long way down the line before I realised or accepted the reality of the situation.

“Again I was incredibly lucky with the support I received from Haileybury. The headmaster Bill Stewart was one of my first visitors at Stoke Mandeville when I was laying there staring at the ceiling and said there and then that my job would be waiting for me no matter how long it took. That was a huge morale booster.

Smiling through adversity: Danny Hearn with his wife Jean at their home in Skibbereen

“When I did finally get back to Haileybury the lads took over and were wonderful. Never underestimate the kids, sorry pupils, because they have a fine sensitivity in these matters. They seemed to just know when I needed to go to the library, or down to the touchline, or needed to rush back up to the school. They were there at all times volunteering to push me and help in anyway. They anticipated my needs and as any disabled person will tell you the most soul-destroying situation is when you have to constantly ask.”

Hearn’s glass seems defiantly half full but there is also a flintiness and dogged persona that has served him well. There was always plenty of grunt behind the smile. As a schoolboy rugby player he was determined but not outstanding and recalls not being able to make the U16 first team at Cheltenham as he progressed through the school before switching from scrum-half to centre and playing in an outstanding first XV in his final year.

At Trinity College Dublin he only secured a regular spot in their powerful first XV – they were at least the match for Oxford and Cambridge at the time in fact probably stronger – in his third year while at Oxford he insists it was an injury that paved the way for his Blue where he contributed fully to a famous shock win over a star-studded Cambridge side. By his own account it was injuries and good fortune that paved his way into the England team.

Even ignoring for a moment Hearn’s innate modesty, his persistence, stickability and bloody mindedness were always there. He was quite pugnacious too, a Boxing Blue who never backed down. A stayer, a man of steel. If a psychologist was drawing up a personality profile of an individual who would be likely to cope with such a life- changing challenge you fancy Hearn would feature highly.

One of the most enduring friendships of Hearn’s life has been with Ian McRae himself. They met again when Hearn visited New Zealand three years after his accident to talk about it around the country and have been thick as thieves ever since. Hearn has stayed with him in New Zealand and vice versa, and when McRae was president of the NZRU back in 2013 he invited Hearn to be his and the All Blacks guests for a few days leading into their Test with Ireland. To see and to feel what a modern day international side is all about.

“What a privilege. When you see them face to face en masse they look so young but then again I’m now getting very old. Above all else it was their discipline and politeness which was extraordinary and which I so rarely see written about. Yet it is at the heart of their genius and pre-eminence.

“One morning they wanted to train quite early and were required to meet in the hotel lobby at 8.30am, maybe even a bit earlier, and I heard Steve Hansen spell it out the night before that there was to be no excessive noise to disturb the other guests who were paying good money for their stay.

“And they were quiet as mice, tiptoeing around like it was Christmas Eve. Anybody who has ever been associated with a high-spirited rugby team will appreciate how deeply impressive that is. They were a great bunch and they are, for goodness sake, still the best team in the world by a distance. Mind you they nearly came unstuck that weekend against Ireland. What a match that was, one of the best I’ve ever seen.”

Given the current debate in the game over the increased physicality, mounting injury list and calls for tackling to be eliminated from the school game it would seem timely to hear from somebody whose view is perhaps more pertinent than most.

“Of course, there has to be tackling and physical contact in rugby at school level, there is no point playing the game without it. That’s a choice you make when you decide to play rugby. Heavy physical contact is part of the game.

“But I will sound a loud warning bell. There is a real problem here which rugby needs to address properly. The game has not finished evolving, there are changes needed. The human race is getting bigger, stronger and faster and that includes schoolboys and now school girls. When I played international rugby I was 5ft 11 inches and 12 stone 4lb. I probably wouldn’t even get a game in the centre at schoolboy level these days. I might scrape a game at scrum-half.

“We are talking about a different game played by different athletes to that which many of us remember not so very long ago. We must be vigilant and clear thinking in drafting – and implementing the laws – so that high tackles, these dangerous tip tackles and these so-called clear outs are eradicated from the game. Not just penalised. That’s not enough. The ruck and breakdown area needs to be more controlled. Rugby has become a much more brutal game to watch – at all levels – it’s gone too much that way.

“There will always be random accidents – some serious – in any physical contact sport and rugby is not alone in that as we know. But the authorities must absolutely stamp out any stuff that has no part in the game and we must constantly coach best practice and method when it comes to tackling and going into contact.”

By any criteria Hearn has led an extraordinary life although not, after his tackle, the life of his choosing. He doesn’t seem to ‘do’ anger but are there any regrets or at least musings about the road not taken? Surely there must be private ‘what if’ moments.

Hearn had made his England breakthrough in 1965 and was almost certain to play against New Zealand at Twickenham the following week and a Lions tour to South Africa in 1968 was a distinct possibility, although he dismisses such a suggestion as a ‘ridiculous notion’. An individual who always loved the outdoors and travel, all sorts of avenues were opening up for him. And then his world was turned upside down.

“I have absolutely no rugby regrets whatsoever,” he insists. “And you are way too generous in your assessment of my abilities. I wasn’t a great rugby player by any stretch, in fact I was an ordinary player. I was quite a tough little so and so but the truth is I just took my opportunities when they came. Today I believe the term is ‘overachieving’.

“No, my only real ‘regret’ is that I was not able to fulfil my ambition of becoming a headmaster. Teaching was always my vocation and joy.

“I would very much have liked to have run a big school like Haileybury. Of course, I might not have been considered remotely suitable or qualified regardless of my disability but there is no question that it effectively ruled me out any way. It’s an all-embracing job, you need to be on call all the time, to be in two places at once, turn on a sixpence, to attend conferences in London or abroad and such. You need to be mobile physically and able to react quickly and after the accident I could be neither.

“But apart from that no regrets. With much help and understanding I did in any case go on to enjoy a wonderful teaching career at Haileybury where apart from the academic side I was fortunate enough to have a couple of outstanding fifteens to work with, one starring Peter Warfield and the other David Cooke.

“To be blessed with two such year groups is not a luxury many school coaches enjoy. I have also been able to travel extensively, particularly to New Zealand which I love as a country and where I spent one long spell on a scholarship helping a research project into injuries resulting in quadriplegia. And I’ve taught in South Africa.

“I don’t feel I’ve missed out in anyway and of course there is that strange but marvellous positive aspect to all this. You somehow act as the catalyst and brings out the very best in some already outstanding people. Out of tragedy – well very trying circumstances let’s not overstate things – can come a huge amount of good. It’s quite remarkable.

“I have been reading and hearing about Matt Hampson and the terrific work he and his friends have done to establish their foundation and build an all-purpose rehabilitation and training facility and hub – meeting place as I understand it – for those who have suffered disabling injuries. I find that very moving and inspiring. My travelling days are nearly done but I would love to meet Matt one day. Both of our lives changed rather dramatically one afternoon at Welford Road. Please pass on my congratulations and huge admiration to him.”

British and Irish Lions

From Leicester reject to a British and Irish Lion: Tommy Freeman’s stellar rise

Latest News

Steve Diamond: Franchise league a good idea

International Rugby

Touring Japan with Wales is my goal says Dan Edwards

You must be logged in to post a comment Login