Barney Davies, a 24-year-old who retired from the game with concussion issues, is urging a new approach

The stigma around toughness in rugby, particularly the expectation to play through injuries, is deeply ingrained in the sport’s culture. However, recent events like the retirement of Guy Porter highlight a much-needed shift in perspective. Porter’s decision to retire early due to concussion-related issues sends a powerful message that prioritising long-term health over short-term glory is crucial. This decision challenges the outdated notion that enduring pain and injury is synonymous with being a “tough” player.

Similarly, when Exeter wing Immanuel Feyi-Waboso chose to withdraw from a Six Nations game last season due to concussion concerns, it further emphasised the importance of taking head injuries seriously. His actions demonstrate that even at the highest levels of competition, the well-being of players must come first. This responsible approach from prominent players will help shift the culture in rugby, encouraging others to recognise the severe consequences of ignoring concussion symptoms.

The long-term issues resulting from inadequate care around concussions in contact sports are increasingly apparent. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), dementia, and other neurodegenerative diseases have been linked to repeated head injuries, with devastating effects on athletes’ lives. The culture of playing through pain not only jeopardises immediate health but also sets the stage for serious, life-altering conditions down the road. The rugby community must evolve to prioritise player safety, we must create an environment where players feel supported in making the tough but necessary decision to step away from the game when needed, whether that be for a short period of time or full retirement.

By addressing these issues head-on and advocating for change, we can protect future generations of players and ensure that rugby remains a sport of camaraderie and respect, rather than one of avoidable suffering.

I am a 24-year-old retired rugby player dealing with prolonged concussion symptoms and the void left by rugby. I am striving to change the stigma in rugby that is to play through serious injury like concussion, leading to worse injury and long term issues.

Rugby was my obsession growing up, starting the first time I watched England play during trips to Twickenham with my Dad. I played for Dorking RFC throughout my youth and made my 1st XV debut at 18, aiming to take rugby as far as I could. I later played for the Surrey U21’s and senior side, making it to the County Championship finals (Div 2) at Twickenham. After that, I headed to Leeds Beckett University to pursue my dream of playing at the highest level. I broke into the performance squad in my first month and made my 1st team debut against Leeds Tykes in my second year, who were in National 1 at the time. This felt like my “big break,” and I believed my rugby career was taking off. But then everything went wrong.

During a sevens tournament, I took a shoulder to the head. Ignoring the symptoms, I played two more games. I felt hazy for the rest of the day but thought little of it. The following week, during pre-season training, I got another knock to the head. Again, I brushed it off. A few days later, on a night out, I got into an altercation while defending a friend, resulting in three people repeatedly hitting me in the head. I was headbutted, knocking out a tooth and causing a severe concussion. The next day, I felt overly emotional and dazed. Something was clearly wrong.

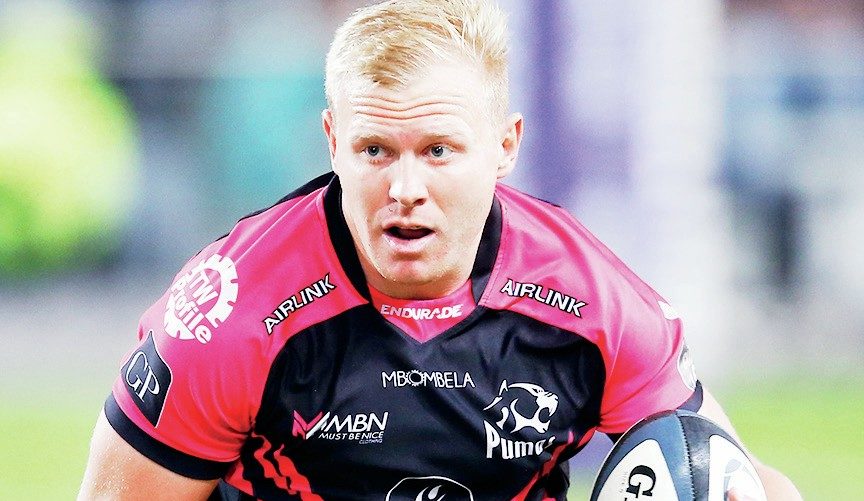

Enjoying life: Barney Davies in his playing days

Enjoying life: Barney Davies in his playing days

I tried to rest and recover, but symptoms persisted whenever I attempted to return to normal activities. When I went back to university, even looking at a screen triggered symptoms, and simple tasks raised my heart rate, which caused further symptoms, leaving me bedbound for days at a time. This continued for over five months as I tried different recovery methods – diet changes, migraine medication, CBD supplements, and more. Frustrated with the advice to rest and wait, I decided to start exercising, forcing myself to do university course work and just getting on with things. I forced my brain to adapt, and three months later, I was back playing. Though not symptom-free, I managed. I played several games for Leeds Beckett, determined to push through to the season’s end and rest properly afterward.

This worked well for me and I felt fully fit going into the new season as the now captain of Leeds Beckett 1st XV which was a huge honour for me, but during pre-season I got another knock to the head from a pretty innocuous tackle but seemed to hit my temple in just the right place. Symptoms were back with the first game of the season just a week away. I of course didn’t mention it to the coaches because that’s the way we are as rugby players and I felt this huge responsibility as captain to continue as I really didn’t want to let anyone down. I played three league games and got two big hits to the head which brought back the worst of my symptoms and I felt as though it was too overwhelming to carry on. This was the last time I played rugby and will most likely be the last time I do.

The next two years were a rollercoaster of depression, anxiety, hopelessness, suicidal thoughts, and a complete loss of identity. I finally admitted to myself that my rugby career was over, though I didn’t tell anyone until nine months later. I felt like I needed to show I still cared and was trying to return to the team. Despite clear CT and MRI scans, symptoms lingered, and I was once again advised to rest. But with symptoms so unbearable, I felt lost and scared. I struggled through my final year of my Business Management degree, trying to complete my dissertation while battling dizziness, nausea, confusion, headaches, visual migraines, and severe depression.

It was at this point where things were so bad that I just felt as though there was no hope for me, my symptoms were only getting worse and I felt that life like this wasn’t worth living. Although I never acted on it, thoughts of suicide crossed my mind several times. However, I didn’t want to give up hope. I’d always been a very happy and positive person, loving life and living it to the fullest. I thought that if I can get 50 per cent better I’d be grateful. I opened up to my family about my issues, they weren’t really aware as they were at home in Surrey and I was up in Leeds still. When I did, they were in shock and obviously very concerned for me, my mother jumping into action and searching the web tirelessly to find help and a solution.

This is when I came across “TheConcussionDoc”, which was the first time I’d found any advice saying that you should start exercising and challenging your brain to get better and over the last 18 months I have managed to very slowly improve.

I have gone through all kinds of treatments including, Hypnotherapy, Emotional Therapy, Aerobic rehab (moderated), Rapid Eye Movement Therapy, Spinology, memory exercises, Vestibular Rehab, Massage Therapy, Dietary tests and changes. This was a journey of trial and error, finding what was triggering symptoms and then looking at the appropriate rehab method to match it.

My recovery journey has been tough as it’s been a long road, but I’m grateful for the progress I’ve made. One of the hardest elements of this whole ordeal was that I’d gone from being this larger-than-life confident rugby player with a friendship circle built around the clubs I played for over the years to suddenly having none of that anymore and feeling lonely and excluded from my friends as I couldn’t train, play and socialise with them anymore. Rugby builds comradery and a sense of belonging to something bigger than yourself, and this was largely taken away from me.

I have now challenged myself with a new purpose which is to stop people making the same mistakes I did. I want to change the game for the better by ridding it of the old fashioned and reckless way of thinking of playing through concussion symptoms and injuries of similar severity for the sake of a Saturday afternoon with your mates. The game is tough and an ability to ignore pain during matches is really important to manage the physicality, but there needs to be a better understanding around the seriousness of playing through injury. Players should be able to make informed and sensible decisions to protect themselves and others so they can continue to play the game they love without fear of long term health implications.

As you can see through my story, I had plenty of opportunity to prevent all the issues I have experienced and certainly could be in a very different position now. Perhaps still playing. I’m not trying to dwell on this, I want to learn from it and help others learn from me so they don’t have to do that themselves.

I see friends take knocks to the head week in week out, but they play on and ignore the warning signs. I can only say so much as it is ultimately their decision, but I think if they knew the extent of the pain that I went through then they may see it differently. I also think if there was more publicity for the potential long term problems; CTE, Dementia, Alzheimer’s and MND/ ALS, then it would also help to change people’s mindset on playing through symptoms. I feel as though I have had a glimpse of some of the issues that people with these illnesses face, having some similar symptoms. The difference is mine went away and the thought of managing these symptoms and worse is absolutely terrifying.

How do I want to do it? I have started an Instagram page – https://www.instagram.com/the_concussion_journey/ – and am looking to start a podcast to prompt the conversation around concussion in rugby and other contact sports. I want to shed some light on other players’ experiences and how they think their lives have been affected by playing through symptoms. I want to get experts talking about the facts around the risks and how they see things changing and ultimately I want to find and communicate more solutions on how to prevent and manage concussions. To be clear, I don’t want the game to change. It is a beautiful sport and one that has brought me some of my best memories, and the physicality is a huge part of it. With this I recognise that an element of concussion is unavoidable, but what we can do is change attitudes so that when these potentially damaging collisions occur that teams and players can react proactively. The short term gain of continuing to play following a significant head knock doesn’t compare with the loss of never being able to play again, trust me I know. So let’s start by changing attitudes and breaking the stigma that exists in the sport that we all love so much.

British and Irish Lions

Charlie Elliott: The 17 backs I would select for the British and Irish Lions

You must be logged in to post a comment Login