WAYNE Barnes may be one of the greatest referees the game has produced, but, if you want to know what gets him out of bed, then look no further than the game between London French and Kilburn Cosmos in November 2015.

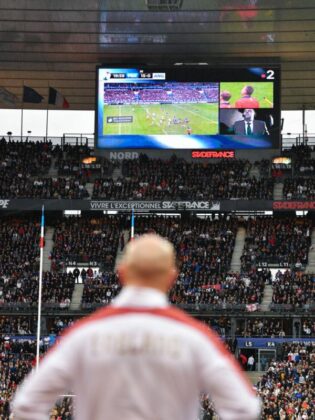

It was a fixture so far below his pay-grade that he could have been forgiven for going home and putting his feet up, but Barnes, who will take charge of his 90th international – which is 40 more than any other English referee – when France face Ireland in Paris in the final match of the 2020 Six Nations, simply cannot get enough rugby.

What strikes you most about the angular, fair-haired Barnes is his sheer enthusiasm for the game, and the people in it, whatever the level. That’s why the London French fixture was like a magnet to the down-to-earth referee who first started to learn his trade as a 15-year-old in the village of Bream in the Forest of Dean, doing three or four matches a weekend, before graduating to become the youngest member of England’s 50-strong national referees panel at the age of 21.

After all, when the first game you take on as a teenage referee is between Bream 3rds and Berry Hill Whoppers, nothing fazes you – and that includes when your European Cup fixture between Racing and Munster is postponed because of the Paris terrorist attacks.

With a free weekend, Barnes phoned the London Society to see if there was a game going – and he was told to make his way to the London French ground in south west London, for their London 3 match against Cosmos.

He recalls: “There were no penalties in the entire 80 minutes, and the players were knackered – but I was presented with a beret and a glass of Chablis as I walked off the pitch. It took me 20 years of refereeing until I got there. It is one of my all-time favourite games.”

Remarkably, it was not a one-off. Barnes managed another penalty-free match in 2017 when he took charge of the 70th anniversary Mickey Steele-Bodger’s XV fixture against Cambridge University.

Much of his success as a referee comes from the empathy, intelligence and common sense that Barnes – who combines his pro rugby officiating with working as a barrister, who now specialises in bribery and corruption – brings to the field.

Returning to his Bream baptism against the Whoppers he says: “It was the old story of 30 players and one referee, and I was the worst referee of the lot. So they told me what to do for 80 minutes, but I enjoyed it – and it went from there.”

Ask him what it is that makes a good referee, and he replies: “The bit of advice that I always give young referees is that you’ve got to get out there and do as many games as you can. You’ve got to learn from your mistakes, and from what it feels like at a scrum when two burly props question your decision.”

A recurring theme with Barnes is that as a referee he wants to add value to the experience of players and spectators. It is a view which has endured despite a severe early storm which might have swamped a less resilient character.

Barnes’ ability saw him progress so rapidly through the refereeing ranks that he was soon promoted through the English Championship to the Premiership, and he made his international debut in the 2006 Pacific Five Nations tournament. It secured him a place on the 2007 Six Nations roster, and then came the quantum leap, at 28, of being selected for the 2007 World Cup referees panel.

It had a sting in the tail when he was given the France v New Zealand quarter-final, which ended with the All Blacks crashing out of the tournament after a 20-18 loss. The match became mired in controversy when Barnes and his assistant referees missed a forward pass leading to Yannick Jauzion’s winning French try.

Barnes became the target of Kiwi wrath, which spilled over into abusive bile on social media, and even included death threats. Barnes reflects that it was one of the hazards of being on a refereeing fast-track.

“In the build-up to the World Cup I had refereed only three Tests, and I was very much the young guy trying to get experience. So, it was a bit of a surprise to be given a quarter-final – and not just any quarter-final, given it was the hosts against the favourites.

“You’re disappointed, because you never want to be mentioned afterwards, but I was, and it probably just drove me to get better. As I said about those early games at the beginning, you learn from your mistakes, and after that game I bloody learnt a lot.”

Barnes says he did not concern himself with the death threats despite becoming the third most hated man in New Zealand, and nor did he duck-out of being sent there on refereeing assignments – including as part of the 2011 World Cup panel.

“My only concern was that there was a urinal of my head put in a bar in Queenstown – but I went back a couple of years ago and now there sits Donald J Trump.

“It’s one of the countries that now hosts me as well as any, I’ve got a couple of cracking Kiwi mates in former refs Glen Jackson and Bryce Lawrence – and the Kiwis are great hosts, who like to talk rugby, and show off their country.

“Of course, I copped a lot of flak at the 2011 World Cup, but it’s all rugby banter – you know, ‘Barnsey, do you know what a forward pass is yet?’. I didn’t do a quarter or a semi, but I did referee Wales v South Africa in the pool stages, and Scotland v Argentina, so I did all right. It was also a New Zealand v France final, so that would have been a brave appointment!”

Ask him if his exclusion from the 2011 knock-out stage was payback for 2007, given that he was in All Black coach Graham Henry’s backyard, and his captain Richie McCaw had been critical of the inexperienced Barnes being given the 2007 quarter, and he shrugs it off. “Who knows? You can only do the games you are selected for.”

Mention of McCaw brings us to the topic of great players whose kudos gives them the ability to influence the outcome of a match, not least through their ability to ‘manage’ referees.

The Barnes response is clear cut, with McCaw, current Wales skipper Alun Wyn Jones, and recently retired Australian flanker David Pocock topping his list. “It’s the ones who know the law, and know when to ask the right question at the right time. Of the current players, if Alun Wyn just says something like, ‘are you sure’, then you think maybe I shouldn’t be. McCaw was always in that bracket, and so was Pocock – he knew the laws about the breakdown, and if he asked you a question he usually had a point.”

He adds: “They picked their moment. Just think about it as a human being. If you are always being told something or constantly being challenged, it’s a cry wolf syndrome. So, if you only get one or two a game you think, ‘he’s got a point’. That’s why those three jump to mind.”

Barnes says there is a different relationship with Premiership players. “We work with them regularly when they are training with England, and referee them a lot more – so it’s slightly more conversational. I tend to like the ones who make me laugh, so Joe Marler brings a smile to your face, even though you’re not sure whether he’s talking to you or himself.

“You want characters in the game – well, I do. Of the old players I think of the likes of Andy Goode, because they wouldn’t so much question your decision as take the piss out of you – and you can have a joke as long as it’s done at the right time and in the right way.”

Continuing to combine his work as a barrister with pro refereeing has helped Barnes to maintain a healthy sense of perspective.

He explains: “When I started as a criminal barrister it meant having to be in court. But in 2009-10 I moved field and started in bribery and corruption, which is a lot less court based, and means I can contribute whether I’m in Tokyo or Twickenham. It’s quite nice learning from both – whether it’s the pressure of a judge staring down at you, or Martin Johnson staring down at you.”

Even though Barnes comes across as good-natured, with numerous references from friends and acquaintances about his talent as an entertaining after-dinner speaker, in great ballrooms or humble club-houses, there is steel in him on the pitch.

This was at its most obvious when Dylan Hartley called him a cheat during the 2013 Premiership final at Twickenham and Barnes red-carding the Northampton captain.

Barnes reflects: “There are certain things in rugby which are a bit like something being dropped on your toe. You say, ‘ouch!’. When someone questions your integrity, it’s an automatic reaction. And that’s what it was – and unfortunately it became the headline. It was just a huge shame it was in such a high profile game, because we want rugby to be painted in a great light, and it wasn’t that day.”

Barnes describes his worst games as those, “when you end up being a headline”. Another match which he does not look back on fondly, for the same reason, is the 100 minute match between France and Wales in the 2017 Six Nations.

The 20 minutes extra of scrum resets, extended by tactical front-row re-substitutions, like that of France’s Rabah Slimani for Uini Atonio, led to charges of sharp practice.

Barnes says that it is wrong to put all the responsibility on referees: “If this is happening it’s up to everybody, including the media, to hold teams to account. Referees say to doctors and physios all the time, ‘is he injured?’. If we are told they are, we have to accept it. I’m a lawyer, not a doctor.”

He adds: “I want it to be like Saracens v Exeter last year, when people were talking about perhaps the best Premiership final we’ve seen, and no-one mentioned Wayne Barnes.”

However, he acknowledges that as long as the scourge of scrum resets is with us, it will spur him on to keep improving as a referee.

“As a fan I don’t want the game to be stopped and slowed, I want the ball to be back in play. I continue to try to learn about the scrum, and that’s why I spend a lot of time with Phil Keith-Roach, because the more I can understand the scrum, the better decisions I make. So, when I say to props, I’d prefer if you didn’t do this, I’ve got the credibility of the former England scrum coach behind me – and that helps.

“Referees need to continue to educate themselves…I’ve never collapsed a scrum myself, but talking to the experts, if you give the players a little bit more time to get comfortable – for instance, adjusting feet and arms on the call to bind – it works, because if you rush that, players get a little bit jittery. That’s why I take a little longer on the engagement sequence. Given an extra second, you get better results.

“Anything which can improve the game, like a more passive engagement, is also worth looking at. So, let’s trial it, and see if it works.”

The quality of Barnes’ officiating saw him given World Rugby’s Referee of the Year award at the end of the 2019 World Cup, and, still only 40, his quest for improvement is undiminished.

For instance, he has adapted to the TMO introduction more constructively than any of his peers, by engaging with the TV official while the ball is in play, to avoid stoppages.

Barnes says: “I’ve always been a big advocate of technology. I think of it as a fan, which is that I want to see the right team win, not because of a mistake, or something that is just impossible to see. How many times is it that you don’t know if the ball has been grounded or not?

“I want those big decisions to be right. So, if there are ways of introducing new technology, I’m always open to that. I’m not saying we should stop the game every two or three minutes to go upstairs to the TMO.

“We’ve got to be good users of that technology, and being able to speak to the TMO as the game is going on can be advantageous in keeping the flow of the game going – and games which do not have that when I am sat there as a fan, are those I don’t enjoy so much.

“I want to add to that spectator experience – and if I can do that by using technology and getting things done quickly, all the better for it.”

The increased scrutiny on referees with more cameras and analysis does not trouble Barnes.

“It comes with the job. There is a saying that ‘pressure is a privilege’. With wanting to be involved with the Lions, and with Grand Slam games, and the Six Nations, I know that it comes with a pressure. But everyone’s got pressure, and you either want to do that job, or you don’t.”

He continues: “However, I don’t put added pressure on myself. I’m not on social media, I don’t type my name into Google, because that’s only going to add to it.”

Barnes says: “I do it because I love refereeing.” He also reveals that stories of his retirement after the World Cup were “totally overstated”. He is still considering his options with his RFU contract due to run out at the end of this season.

He has decided that whatever path he takes refereeing will still be part of it. “When I finish as a professional referee I will definitely be going down to do London Welsh 4ths, or Richmond Heavies, a bus ride from Twickenham where I live, and refereeing for the London Society – and cashing in that lovely tradition of a couple of free pints!”

From where we sit, 40 is too young for Wayne Barnes, the best referee of the pro era, to leave the big stage.

British and Irish Lions

Charlie Elliott: The 17 backs I would select for the British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions

Charlie Elliott: The 21 forwards I would select for the British and Irish Lions squad

You must be logged in to post a comment Login