As we nudge into 2022 it’s time to officially celebrate 150 years of Cambridge University rugby even if recent research suggests the Light Blues actually got underway a year earlier than thought in 1871. No matter, it’s been a hell of a ride and although it still pains Cambridge types a little that Oxford were first out of the blocks in 1870 it would be impossible to overestimate their massive influence on the game generally.

That of course also goes for the Dark Blues but for this year at least it is Cambridge’s turn to take a bow and hog the limelight and a big part of that process revolves around the publication of 150 years of Cambridge University Football Club – the official history of the club.

It’s a sumptuous pot pourri, dip in, liquorice-all-sorts of a book which not only plots the basic narrative but bombards you with facts, information, trivia, gossip, cherished memories, familiar faces and those you have never heard of but frankly should have.

Rob Cole, the esteemed Cardiff freelancer and founder of Westgate Agency, is the man who as editor in chief and star contributor must take the plaudits for masterminding this beautifully-produced tome which shows all his hallmarks.

He always knows the story behind the story, his attention to detail is second to none and that underpins this very special club history. There is no anecdote left untold, no statistic and fact that has not been unearthed and accurately recorded, it is both a great read and the definitive document of a record which is a rare trick to pull off.

In the spirit of full disclosure I must immediately inform you that at Rob’s request I chipped in with one chapter along with a number of other guest contributions including Peter Jackson, also of this parish.

It’s not a book to read in one sitting, there is just too much to absorb so take your time. The great, perpetual, swirl of Cambridge rugby in many ways reflects the history of the game itself and the big names and their stories hit you from every which way. Jonny Hammond, Arthur Rotherham KG McLeod, David Bedell Sivright, Wavell Wakefield, Carl Aarvold, Micky Steele-Bodger, Wilf Wooller, Cliff Jones, John Gwillam, Arthur Smith, Clem Thomas, Ken Scotland, Gordon Waddell, Mike Gibson, Gerald Davies, Gavin Hastings, Rob Andrew, Chris Oti, Alastair Hignell, Mike Hall, Adrian Davies, Eddie Butler, Rob Wainwright et al

I’d better stop there, we are talking about 352 Test players from 17 nations. An all-time Cambridge back row alone would take you until chucking out time to select while a Cambridge Dream Team back division would require an all-night lock in.

“A Cambridge back row would take until chucking out time to select”

Then there is the development of the game itself with various great Cambridge teams and individuals progressing the sport to new levels; the vast history of their rivalry with Oxford and the enormous contribution and sacrifices Cambridge Blues made during World War One and Two – deaths and losses that were replicated at every club in the land.

There was the great amateur-professionalism debate in which Cambridge occasionally stood accused of riding both horses. To be a Cambridge rugby player – or indeed a Cambridge Olympian in the 1920s – was as close to being an elite professional as it was possible to be without being a social outcast in those very different times. More of which anon.

There are the academic high fliers, sportsmen who walk into their chosen college and seemingly knock out a first class honours degree or 2:1 in their spare time and then the grafters like Phil Keith- Roach, who struggled initially at school and had to complete his A level studies while a PE teacher in Croydon to achieve suitable grades. Having done that, but still a rank outsider, he identified a rugby friendly college – Pembroke – and armed with a 40,000 word thesis on scrummaging secured an interview in which the dark arts featured prominently. An hour later he was a Cambridge man and having got the academic ‘bug’ he made off with a 2:1 in archeology and anthropology.

Then there is the great touring tradition – infamous forays into France with Wakefield literally leading the charge on one drunken night – while there were regular trips to the USA, South Africa, Argentina and the Far East. Dozens of national captains to note; scores of Lions tourists, a handful of the game’s most noted broadcasters and scribes; great administrators and talented maverick coaches not least the inimitable Tony Rogers who ruled the roost for 30 years or more. And, of course, the remarkable Steele-Bodger who defied categorisation and was ever present for 70 years one way or another.

There have been memorable unbeaten seasons up to the Varsity match – 1903 and 1961 come to mind although the latter went on to beat Oxford as opposed to lose; famous wins over national sides, notably Australia in 1957, and shining stars who alas died far too young.

Once such was the Buenos Airesborn Barry Homes, a brilliant Blue at full-back in 1947 and 1948 who earned a place in England‘s Five Nations team in 1949. That summer he returned home to Argentina and played in two Test matches for the Pumas against France. In the November he married and six days later he died of typhoid fever in Salta.

Then there was James Monahan, a young giant at tight-head prop who started for Bath as a schoolboy, starred in the 1967 and ‘68 Varsity matches but died suddenly in his bath at home in Wiltshire when on the verge of great things.

On occasions the club have been so strong, notably 1957, that the LX club – effectively their Second XV – beat the Blues team in a full-on game. Rather like that occasion when Wasps seconds beat the club first XV in a heated warm-up game before their first Heineken Cup Final win, the Cambridge First XV then went on to beat the Australian tourists with four of the second XV being promoted to starting duties.

And there is more. At various times – like rugby itself – Cambridge have struggled financially and had to reinvent themselves and the Varsity match while for many decades they assiduously courted the best Scottish and Welsh schools in particular to scoop up the cream of the domestic crop to counter Oxford’s seemingly endless supply of often much-capped, Rhodes scholars from the big three SANZAR nations. Fettes alone have provided 12 Cambridge captains.

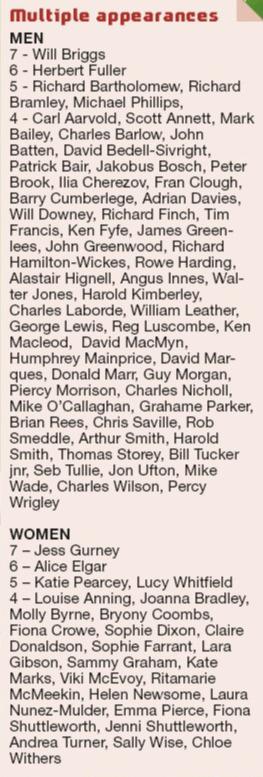

And what about women? Cambridge’s first rugby interaction was when high-spirited suffragettes tried to burn down their Grange Road pavilion, but things have picked up recently with the formation of a side in 1988 and the start of the women’s Varsity match and a blossoming section of the club. At the recent 150th anniversary dinner, a third of those attending were former or current women players.

All this cascade of rugby excellence started, officially, back in 1872 with a defeat at Oxford and although there were glorious periods of Cambridge dominance in the first 100 years or so, the Light Blues didn’t actually draw ahead of the old enemy in terms of games won until 1981, since when they have not been headed. It’s still pretty tight though with 64 wins to 61 and 14 games drawn.

Although for many years viewed as one of the big three Varsity clashes along with cricket and the Boat Race, Cambridge didn’t get around to awarding rugby Blues until 1885, the ninth such sport to be so honoured and well behind billiards and steeplechasing.

Early matches were staged at Parker’s Piece, as was the second Varsity match in 1873, but since then it has always been on the neutral ground save for the unofficial Wartime Varsity matches. Grange Road was purchased for £4,100 in 1896 and has been the club’s spiritual home ever since.

Although Cambridge had excelled many times before the arrival of Wavell Wakefield in 1921 there is no question that few did more to shape the future of the Light Blues and establish the enduring rugby culture.

Wakefield, on a twoyear RAF scholarship, was appalled when the team slipped to a sloppy defeat against Oxford that year. He took it personally and when he was elected skipper for the 1922 season in the January of his first year he set about rebuilding the side and club immediately.

He started by insisting that only those available for the Varsity match in December later that year play during the Lent term fixtures, which might seem obvious to us now, but was revolutionary at the time with Cambridge having a number of prestigious fixtures to fulfill during that period after Christmas.

He encouraged the recently formed London Cambridge team, who organised occasional fixtures in the Lent term, and was delighted when Scottish rugby playing students followed suit and formed their own Cambridge Scottish side. Cast the net wide.

Wakefield also headed up a team of scouts who made a point of watching all the college matches during the Lent term assessing only those who would be returning for the following academic year and concentrating on those who had not already been picked up by the system that season.

College captains were also instructed to send in detailed reports of any particularly bright talent among the Freshmen in their teams that might have escaped attention during the official trial matches. It was very regimented, very RAF.

Using his many contacts, Wakefield enlisted a number of guest coaches for the Blues team although, officially of course, that term was frowned upon while Engineer Captain S Start, one of the officers in charge of Wakefield’s course at Cambridge, was a top referee and took the team and squad through their places in that respect. Knowing the laws and how to use them to your advantage was crucial. Wakefield was always the master of that.

Showing an athlete’s appreciation of peaking, Wakefield drove his side very hard physically in the first half of the term, but then banned his squad from even getting changed into rugby kit in the final ten days leading up to the Varsity match. Instead, he substituted a few light running sessions at Fenner’s to occupy the build-up to the Twickenham showdown.

Wakefield had the reputation of being a hard driving, spartan taskmaster, but it was he who insisted on doing away with the tradition of early morning runs before breakfast which he considered futile and solely the preserve of the monastic half-witted oarsmen, who could be seen pounding the streets before first light. Succeeding generations of rugby players can thank him for their leisurely mornings.