Brendan Gallagher continues his series looking at rugby’s great schools

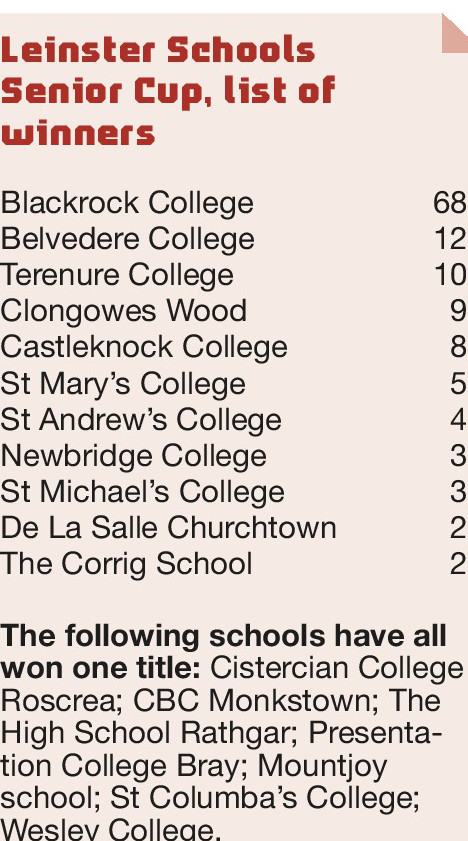

BELVEDERE College, like all Leinster schools, have always operated in the shadow of mighty Blackrock College on the rugby field but the Dublin school does specialise in producing the occasional truly great player and/or ripe rugby character.

This is the school that gave us Thomas Crean VC, Olympic gold medallist Noel Purcell, Irish legend Eugen Davey, Grand Slam captain Karl Mullen, Sir Anthony O’Reilly, Ollie Campbell, Cian Healy – indeed they have produced 32 Ireland internationals to date. Players from Belvo – as the school is universally known – tend to make a splash one way or another.

In a Leinster Schools Cup dominated to an extraordinary degree by Blackrock – whose 69 titles are more than all the other schools combined – Belvedere with 12 titles and Terenure College with ten are the only schools who have managed to seriously contest the issue over the years.

Most gloriously there was a rare double in 2005 when Belvedere’s senior side, spearheaded by fly-half Ian Keatley, won the U18 title and their Juniors also took the U15 Cup.

Starring for the juniors that day against Terenure College was future Ireland and Lions prop Cian Healy although it was future Leinster and Rotherham wing Michael Keating who scored their two tries. That U15 year group went on to provide the basis of the team that also won the U18 title in 2008 while there was a notable era of success in 2016 and 2017 when they won two senior titles on the bounce.

The success in 2016 was much deserved for a strong era, after Belvo teams had lost two successive junior cup finals and one senior cup final in the previous three years, the latter against Cistercian College Roscrea in 2015.

It was against the same opponents 12 months later that Belvo, with the versatile Hugh O’Sullivan – now one of the young tigers at Leinster rugby – pulling the strings, outscored their opponents five tries to one en route to a comfortable 31-7 win at the RDS.

Sullivan was one of the main men again 12 months later when the going was much tougher against Blackrock, but Belvo had the bit between their teeth – it was a rare opportunity to put one over the old enemy – and they ran out 10-3 winners in a tight affair.

Quite a bit further back came the Ollie Campbell era with one of Ireland’s greatest ever flyhalves starring – at full-back and centre – in back-to-back finals, helping them to a 14-11 win over Presentation College in 1971 and then a 20-10 victory over Terenure College. Even earlier there were a clutch of titles for Belvo in 1923 and 1924 followed by isolated wins in 1938, 1946, 1951 and 1968. But that’s the sum of it to place against Blackrock’s 69 titles.

Two early notables, although not contemporaries at the school, were forwards Thomas Crean and Andrew Clinch who played for Ireland together and enjoyed notable success in South Africa in 1896 when they were part of a formidable Ireland contingent and played in all four Tests.

The remarkable Crean, who learned his rugby at Belvedere before moving to Clongowes wood, achieved fame on and off the field and like many young sportsmen excelled at everything including swimming which for many decades was considered Belvedere’s premier sport.

It was his swimming ability that first brought him public acclaim when in September 1891 he led a number of other students in rescuing a drowning man – Wim Ahern – off the coast at Blackrock. At the age of 18 he was awarded the Royal Humane Society medal for his prompt actions.

As a forward he was renowned for his strength and pace and stood out like a colossus in the Ireland team that took the Triple Crown in 1896 and then provided the rump of the Lions tour party to South Africa. With the Lions English captain Jonny Hammond suffering a serious injury early on tour, Crean took over the leadership in two of the four Tests and contributed massively to the 3-1 series win.

He loved it in South Africa, settled in Johannesburg, played for the Wanderers clubs there and set up a medical practice in the city before joining the Imperial Light Horse two years later when the Boer War broke out.

Crean was 28 when he was awarded the Victoria Cross. On Dec 18, 1901, during the action at Tygerkloof Spruit. Although wounded himself, he continued to attend to the wounded in the firing line, under heavy fire at only 150-yards range. He did not stop until hit a second time, when he was seriously wounded and left for dead although he was later discovered still alive and rushed to a field hospital.

On returning to Britain in 1906 he set up a practice in Mayfair but of course joined up at the outbreak of WWl when he commanded the 44th Field Ambulance section of the British Expeditionary Force. Again he attended to the sick with great diligence and valour, twice being mentioned in despatches and also being awarded the DSO.

The Great War, though, took a toll on his mental and physical health. He did briefly reappear as a public figure when, in his capacity as the course doctor at Ascot, he jumped onto the circuit to perform an emergency trepanning operation – with a hammer and chisel – to save the life of a jockey. Thereafter though he declined steadily and started drinking heavily as his business declined. He also developed chronic diabetes and died a broken man in 1923.

A dashing figure in his prime, his son Pat was cut from the same cloth and was Errol Flynn’s stuntman throughout his Hollywood career.

Noel Purcell was another remarkable one-off who as well as playing for Ireland represented two countries – Great Britain and Ireland – at the Olympics. At school, in the best Belvo tradition, he was outstanding at swimming and waterpolo while he also excelled in boxing and captained the First XV although it wasn’t a vintage year and they made no great impression on the Leinster Schools Cup.

His sporting career other than a lifelong devotion to swimming spluttered after leaving school as his studies to become a solicitor took over, followed by the massive disruption of World War 1.

Having survived that, although he was injured on the western front, he competed with renewed zest in peacetime as he approached 30.

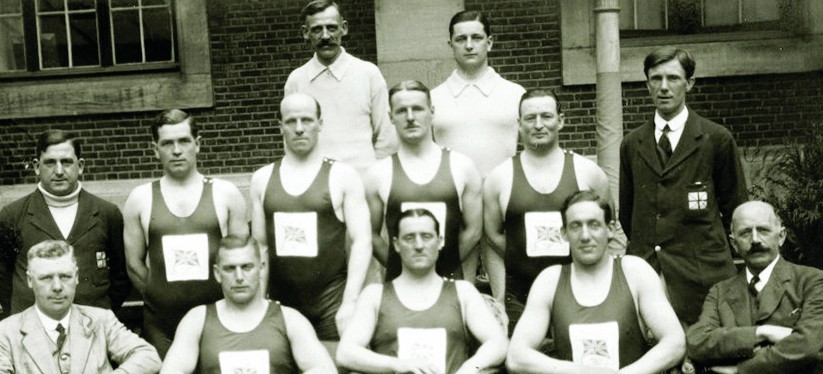

First he forced his way into the GB water polo side for the 1920 Olympics. Initially the idea was to pick the England team en masse but after protests a trial match was organised between England and the Rest of Britain which then included Ire- land, Scotland and Wales. The Rest, with Purcell to the fore, won 6-0 and the squad was radically altered.

For the good as it turned out, with Great Britain and Purcell taking a surprise gold medal, beating Belgium 3-2 in the final. The key to success had been a remarkable 7-2 win over tournament favourites USA in the semi-final.

Back in shape Purcell took up rugby again with a vengeance and in no time found himself an ever-present for Ireland at flanker in the 1921 Five Nations. At the age of 31 and with family responsibilities he decided that was enough on the rugby front but in 1924 returned to Olympic action in the pool, captaining the Ireland squad that got through to the quarter-final.

A few years later, having put on a bit of timber, he became a referee and took charge of the 1927

Five Nations game between England and Scotland only to be admonished by The Times for his failure to keep up with play and “refereeing casually and from a great distance”.

Eugene Davey was another huge name in Belvedere circles between the wars, making his first impact in 1919 when he captained the U15 side to the Leinster Junior Cup although to his chagrin Belvo could not get any kind of run going when he captained the First XV two years later.

During his international career, between 1925 and 1934, Davey was virtually ever present and won 34 caps which was a huge number in the days when Tests were largely restricted to the Five Nations and, after France‘s expulsion, the Four Nations. His most notable achievement came in 1930 when he scored three tries in eight minutes during Ireland’s 14-11 win over Scotland at Murrayfield.

As for Karl Mullen, he started his schools career at prop before moving to hooker and appeared in the team that lost the senior cup final to Castleknock in 1944.

Although he was never a captain at school, that soon changed as he made his way through the ranks.

In 1946 he was one of six Belvedere old boys to play in a victory international against England – Jack Belton, Des Thorpe, Brendan Quinn and brothers Kevin and Gerry were the others – and two years later he led Ireland to their first Grand Slam.

There was a Triple Crown in 1949 and then he skippered the Lions on a memorable tour of New Zealand and Australia in 1950.