Over the years camp followers have suffered from severe sunburn, hypothermia and trench foot watching the HSBC Rosslyn Park School Sevens but that all comes with the territory at a unique and special rugby gathering which celebrates its 75th anniversary this week.

Over the years camp followers have suffered from severe sunburn, hypothermia and trench foot watching the HSBC Rosslyn Park School Sevens but that all comes with the territory at a unique and special rugby gathering which celebrates its 75th anniversary this week.

The rugby is always engrossing – sometimes truly spectacular – and combines perfectly with a de-mob happy nostalgic end-of-season feeling. Professional rugby may have become an 11-month of the year business but for the schools this is their last hurrah until September.

If you prowl the touchlines long enough, particularly on the main show pitches at the Richardson Evans Memorial Field just off the A3 you will encounter a plethora of Premiership directors of rugby and academy coaches – and a fair few from the Championship to boot – as they mingle and try to look as uninterested as possible. The little dictaphones and notebooks they occasionally retrieve from the cavernous pockets always give them away, that and those dainty opera type binoculars which even enable you to watch some matches from the bar.

The Sevens is an absolute godsend for talent scouts, a massive gathering and quasi clearing house of all the best youngsters in the land at various stages of their development in a sporting environment where strengths and weaknesses are magnified. Afterwards, in the cheery beer tent, the club representatives can quietly tap up the parents and school coaches of those who have caught their eye. All very civilised.

A considerable array of seismic talent has starred at the Rosslyn Park Sevens – from Gareth Edwards, Terry Price, Keith Jarrett, Will Carling, Rory Underwood, Lawrence Dallaglio, Iain Balshaw – but also a massive number of the stalwarts who make up the wider club game in England and Wales especially. It is an early rite of passage for virtually any player of any ability or ambition. Since the start of the Millennium nearly 80,000 players have appeared at the Rosslyn Park Sevens and the majority of those are still active in some capacity.

Their common ground and shared experience is the Rosslyn Park Sevens.

For many it is also their first experience of that extraordinary phenomenon known as the “Rugby Tour”. Pile into the school mini-bus at some ungodly pre-dawn hour, six-hour motorway drive without comfort break, uncomfortable beds and toilets smelling of chlorine at some school dormitory in southwest London, two days knackering rugby, scuffed knees, scabby elbows and painful black eye followed by cold showers.

Then life starts looking up – some crafty ales in the beer tent and then a few more at that obliging local near your billet followed by a singsong. Another bleary-eyed start the following morning and its back up the motorway with many tales to tell, some of them even true.

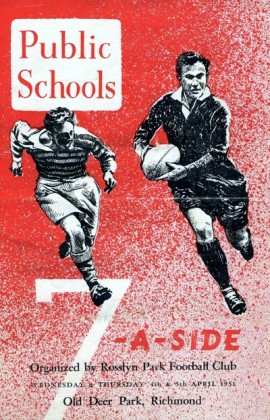

It all started in 1939 as a modest privately run Sevens competition for 20 public schools with St George’s Harpenden beating Clifton 10-8 at the Exiles Club at Orleans Park near Twickenham.

This year there will be 389 schools entering 650 teams in six competitions with 1,275 matches scheduled over five days. Its claim to be the biggest annual rugby competition in the world – 7,000-plus participants – has never been threatened and increasingly it has become a triumph of logistics as much as anything else.

Journalistically, before the digital computer age, phoning in the result of every game was an Everest to be scaled although relays of tea and buns provided by Geoff Dodds, competition controller, eased the pain a tad. After 5pm, which he judged a reasonable hour for young men to start drinking, Geoff would also start sending beers into the broom cupboard which doubled as a press office.

For decades the entire five-day extravaganza was heroically stitched together on a shoestring by the husband and wife team of Peter and Rose Tanner with scores of club members taking a week’s holiday off to offer their services along with the massed ranks of the London Society of Referees.

Nowadays the Rosslyn Park management board, backed by the largesse of HSBC, oversees the tournament but the back-up team is essentially the same. Having moved from what is effectively now London Welsh’s in 1957, for many years the main finals were held at Rosslyn Park’s ground but increasingly eight hours of knock-out matches on the solitary 1st XV pitch in the Open Championship on the last Friday of the tournament left said pitch in a sorry state for Park’s following senior club fixture.

Now all the main finals are held down at the Richardson Evans Memorial Playing Fields where the main tented village is also situated and provides the social hub-bub.

That St George’s side in 1939, incidentally, included two particularly interesting characters. Their speed merchant was Dennis Watts who later became the British triple jump champion and indeed the GB national athletics coach while their fiery hardman flanker, whose tackling won the day in the semi-final against favourites Cheltenham, was a youngster called Michael Heron whose career and life took the most unexpected turn.

Come World War Two he became a conscientious objector and drove ambulances in the Blitz – one of the most dangerous jobs of all – and after hostilities he became a Benedictine monk, disappearing from public life in 1954, taking Holy Orders at Christ the King Monastery, in Cockfosters.

In 1999, 60 years to the day from his big rugby moment, Heron was persuaded to finally return to Park for the morning: “Dennis was a our real star,” he told me. “Cheltenham had a wing TGH Jackson – the ‘Cheltenham flyer’ – who was reckoned to be the fastest schoolboy player in the land but Dennis comfortably saw him off in the semi-final and he also scored our two tries in the final. We were a bit lucky in that we played in the first semi-final and were more rested, but we were a small school up against the big boys really.

“I didn’t have a religious thought in my head in those days, in fact I refused to be confirmed – I always thought it was God’s way of getting back to me when he called me to the Church!”

Talking of sprinters a certain Gareth Edwards first made the rugby world sit up and take note at Rosslyn Park in 1966. Edwards had been spotted initially by Millfield as an athlete and indeed later in 1966 he broke the British Schools record for the 220-yards hurdles, recording 22.5secs in a race including future Commonwealth Games 400m hurdles champion Alan Pascoe. Edwards could really shift.

Under its founder and headmaster Jack “Boss” Meyer, Millfield become rugby-mad and Edwards’ true genius found expression and before long he had won Welsh schoolboy caps. Come 1966, though, and Millfield still had not won Rosslyn Park and, worse still, Edwards had badly damaged an ankle playing football and missed all the first term of rugby. Twice a week Meyers’ wife Joyce, another rugby fanatic, drove him for treatment in Bristol and as he recovered it was her who put him on the spot.

The Sevens that year clashed with the England-Wales Schools international at Twickenham. Which was it to be? Edwards, for the only time in his life, put Wales on the backburner and went on to dominate the competition with his clever, slow slow, quick tactics. Nobody could touch him when he hit the afterburners and with Edwards at the helm Millfield reached the final and then beat Whitgift 21-0.

“That tournament and that final in particular is still one of my fondest rugby memories,” recalls Edwards. “I can still remember the speed and the pace of everything, you really had to up your game. Rugby under Boss Meyer was a religion, just like Wales I suppose, and he and Joyce really wanted to the School to win that tournament.”

The Welsh Schools were on fire for much of the Sixties. Llanelli GS, with a mesmeric wing Terry Davies doing most the damage, won three Open titles at one stage while a strapping Monmouth back called Keith Jarrett made a big impression in 1967 although his team did not take the title. Three weeks later he scored 19 points in a sensational Wales senior debut against England at Cardiff Arms Park.

Up until 1970 there was just the Open and Prep School tournaments but that year saw a major change with the Festival tournament introduced for teams that play rugby for just one term while the Open was predominantly the domain of the two term schools and generally considered the tougher event although Wellington College might dispute that having dominated the Festival in recent years – nine wins since 1999 – and transformed the shorter version of the game almost into an art form.

Millfield have consistently proved the team to beat in the Open competition but the single greatest achievement in the Sevens history remains that of Ampleforth in 1989 when they claimed a unique double taking both the Open and the Festival, winning 16 matches in total during four days of heavy ground underfoot – four hours of flat-out Sevens.

Nobody can actually remember why Ampleforth were, unusually, allowed to play in both competitions that year although the truth is probably that the rules did not actually prohibit such an audaciously ambitious raid. The 1989 tournament was the making of one Lawrence Dallaglio, a lower sixth student who up to that point had been only an occasional member of the 1st XV. Dallaglio was drafted in for his pace and athleticism and those four days at Rosslyn Park ignited his competitive juices.

He loved the one-on-one combat that Sevens often involves and as Ampleforth’s marathon week continued he emerged as the fittest of the fit in a talented squad that included another three players – Guy Easterby, Paddy Bingham and Richard Booth who went on to play a good standard of senior rugby.

“It was a bit of an eye-opener,” says Dallaglio who was listed as Dalzaglio in the official winners’ pictures. “Sevens was a big thing for Ampleforth and we went down a couple of days before and stayed in a dormitory down at Crystal Palace where we trained a bit over the weekend before the tournament started.

“We also went to a Nigel Benn fight at the Royal Albert Hall which was pretty brutal and then came the two tournaments, first the Festival and the Open. It was a marathon and there were some close calls, I remember a particularly tough game against Neath College en route to the Open Final.”

Other developments along the way has been the introduction of a Girls tournament in 1994 and the arrival of teams from all corners of the world as more and more wanted to sample the unique atmosphere for themselves.

Most notable was probably Future Hope School from Calcutta, founded by Tim Grandage to rehabilitate orphans found sleeping rough on or around the 26 platforms of Howrah Railway station in central Calcutta.

Grandage, from Rugby School appropriately enough, used a devotion to rugby as his main tool in getting the lads fit and promoting teamwork and they made their debut in the Colts tournament in 2002 when Sir Clive Woodward absented himself from England duties to come along and coach them for the morning.

They did not win, in fact they took a couple of thumpings, but afterwards they poured a few ales down their throats and rightly considered themselves fully paid-up members of the rugby brotherhood. They had played at the Rosslyn Park Sevens and got the bruises to prove it.