THE MAN TRULY IN THE KNOW

OWEN Farrell‘s maternal grandfather had only just begun creating the ultimate Anglo-Irish dynasty when word from the other side of the Rubicon stopped both codes in their tracks.

In the spring of 1972, Barry John, Union’s prototype superstar then at the zenith of a stratospheric career, revealed his immediate retirement. The news that the most celebrated fly-half of his generation had been driven into premature retirement by the penalties of fame startled followers on both sides of rugby‘s Great Divide.

What impact it had on Keiron O’Loughlin, fresh from finishing his second season at Wigan, is not known, beyond sparing him exposure to an opponent whose elusive quality suggested that he might have been made of mercury.

If the Welshman’s sudden retirement passed O’Loughlin by, the same could not have been said of his employers. His home-town club and arch-rivals St Helens made suitably hefty bids, each aware of their quarry’s jobless status after he had given up a teaching job to tour South Africa with the 1968 Lions.

Luckily for Cardiff, Wales and the Lions, John stayed put but not for that long. Instead of going north at the age of 23, he was gone at 27 of his own free will, relieved to be out of the limelight rather than go on wrestling with the celebrity lifestyle that had been foisted upon him.

Nobody talked about the subject half a century ago in respect of successful sportsmen or women but, put in modern parlance, Barry John had quit for the good of his mental health. O’Loughlin would have been suitably dumbfounded had he been told that one day his grandson would cite the same reason for making himself unavailable to England.

John and Farrell could hardly have been more different, in background, personality and, most strikingly of all, as fly-halves: one revelling in the art of finding space, the other in physical contact.

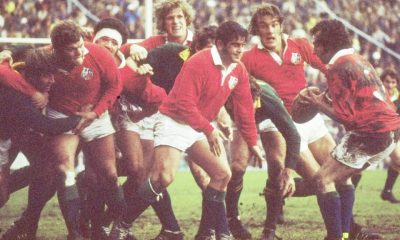

Each had been through a very different emotional wringer, one which brought them to the same shattering conclusion, that they’d had enough, in John’s case for good. The sight of him ghosting through serried ranks of All Blacks for the Lions in the summer of 1971 hot on the heels of helping Wales win a Grand Slam made him a global superstar.

Ever accessible to the multitude of adoring fans, even the most personable of young men found the public adulation too much. The tipping-point came shortly after the late Eamonn Andrews and the This Is Your Life crew ambushed him at the end of an England-Wales match at Twickenham.

John had travelled north to lend lustre to an event in Rhyl. “I opened the extension of a bank and after I’d been introduced, this little girl came forward and curtsied,” he said in Lions of Wales. “Everyone thought it was wonderful. They were clapping like mad.

“That was when it came home to me that this was all getting out of hand. If I needed something to show me that it had all gone way over the top, that was it.

“That is in no way meant as a criticism of the little girl but it embarrassed me. It means that some people had put me on such a pedestal that it was as if I was from another world. I decided I would retire at the end of that season. I’d had a gutsfull.”

In the finest showbiz tradition, he left the grand stage with the crowd in raptures. None of the 35,000 who paid to be at the Arms Park on April 26, 1972 to watch a pride of Lions in action for Barry John’s XV against Carwyn James’ XV in aid of Urdd Gobaith Cymru, the Welsh League of Youth, had a clue that they would never see him in action again.

He had confided in two trusted compatriots just before kick-off – Gareth Edwards and Gerald Davies. Both had been sworn to secrecy pending final negotiations for the revelation duly splashed all over a Sunday newspaper a few weeks later.

Those too young to have seen him in the flesh can be forgiven for not appreciating that the game had lost its Pied Piper. The late Cliff Morgan, a fly-half out of the same outrageous mould, summed it up best: “You’d have paid an extra £10 at the gate if you’d known Barry John was going to be playing that day. I loved to watch him.”

Even now, after all these years, his early retirement is still debated by his contemporaries and those who paid to watch him and marvel at what they saw.

Of course there were commercial reasons, not least a well-paid job as the star signing for The Daily Express in what was still Fleet Street and with it a platform in every corner of Britain and Ireland.

“I felt I had at least a couple more years at the top,” he once said. “But only if I could be me. The celebrity thing was getting in the way of that.”

Barry will be 79 in a month’s time. Keiron O’Loughlin turned 70 earlier this year. His son Sean retired recently after a career monumental even by Wigan standards, his daughter Colleen is married to the coach-of-the-year Andy Farrell. How England will cope without their son, heaven only knows…

You must be logged in to post a comment Login