PETER JACKSON

THE MAN TRULY IN THE KNOW

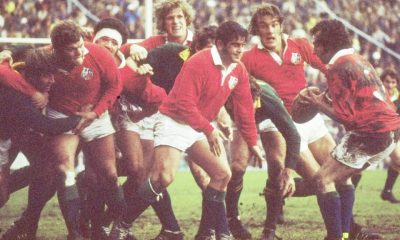

Stewart McKinney’s name will forever be enshrined in the Lions pantheon alongside the few whose invincibility in South Africa can never be matched let alone superseded.

Just as the ferocious Ulsterman and his 29 team-mates left an indelible mark on the sport as well as the Springboks of 1974, so the game has left an equally indelible mark on him in the cruel form of an incurable condition. It has prompted McKinney to take a decision for the long-term good of the game.

“My brain will be donated to Queen’s University to help the work of their research team,” he says. “Why not? Sure it’ll be no use to me once I’m gone.

“I’ve no intention of giving it away for a while yet. My wish would be that it helps future players with whatever problems they may encounter.”

There is a Dungannon dimension to his decision. Lucy Turkington, a member of the Ulster women’s team who learnt her rugby skills at McKinney’s Dungannon RFC, is studying brain damage at Queen’s.

McKinney, whose bringing to rough justice of the Eastern Province player responsible for rabbit-punching Gareth Edwards passed into Lions folklore long ago, has been hit by something not even he can defeat, dizziness.

“Some days it’s worse than others,” says Ireland‘s wing forward from the Seventies now slightly more than halfway through his own seventies. “I got four whiplash injuries through playing rugby and they affected the artery to the brain.

“We played France in a friendly except they can’t have told Alain Esteve of Beziers. I was standing in a lineout and he came up at a hundred miles an hour and smashed into me.

“My head went back and I didn’t know where I was. That was my first whiplash injury. The second was against the All Blacks. The third was caused by a late tackle in the Omagh Sevens and the last one was with Dungannon.

“An accumulation of the whiplashes caused fractures in my neck. Remember, there were no substitutes in our day. You’d be examined by a doctor and sometime he would be the doctor of the opposing team.

“The big problem I have now is with dizziness. I’m dizzy every day. Some days I’m very dizzy. It’s been like this now for many years.

“I had a wonderful, wonderful time playing rugby. I’d never say a word against the game”

“There’s absolutely nothing they can do about it. When it’s very bad, I have to sit down. I had a brain haemorrhage five years ago which was massive. I’m lucky to be alive. It affected the sight in my left eye. I’ll never drive a car again but I’m over 65 and I have my bus pass. These things happen.”

McKinney will not be joining the long list of players taking legal action against their respective national Rugby Unions and the sport’s governing body, World Rugby.

“I had the best years of my life playing rugby. I had a wonderful, wonderful time. I do not hold it against rugby and I never will. I’d never say a word against the game.”

Despite his health issues, McKinney made it to the Irish Embassy in London a few days ago for an occasion to mark the 50th anniversary of England’s appearance in Dublin despite Scotland and Wales staying away for security reasons.

McKinney made it thanks to the helping hands proffered by those with whom he stood shoulder to shoulder back in the day: Willie-John McBride, Mike Gibson, Dick Milliken, Tom Grace, Kevin Mayes, Johnny Moloney, Tony Ensor, Pat Whelan and Seamus Dennison.

They acknowledged their enduring appreciation of England ensuring that the fixture went ahead. The Red Rose’s Embassy line-up, among them Steve Smith, Chris Ralston and Tony Neary, had been shortened by the unavoidable absence of, among others, Roger Uttley, Peter Dixon and Fran Cotton.

“If England hadn’t turned up that day, it would have been a huge setback for rugby in Ireland,” says McKinney. “The debt we owe them was stressed time after time during our reunion at the Embassy.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login