Clive Rowlands woke up yesterday with the same ache in his lower back, just as he has woken up every Saturday for more than half a century. One late hit from Colin Meads has lasted a lifetime.

Clive Rowlands woke up yesterday with the same ache in his lower back, just as he has woken up every Saturday for more than half a century. One late hit from Colin Meads has lasted a lifetime.

“I get pain every morning,” said Rowlands. “I suppose the natural process of getting older doesn’t help but I don’t have a problem with Colin Meads, not really. I’ve got no hard feelings about it.”

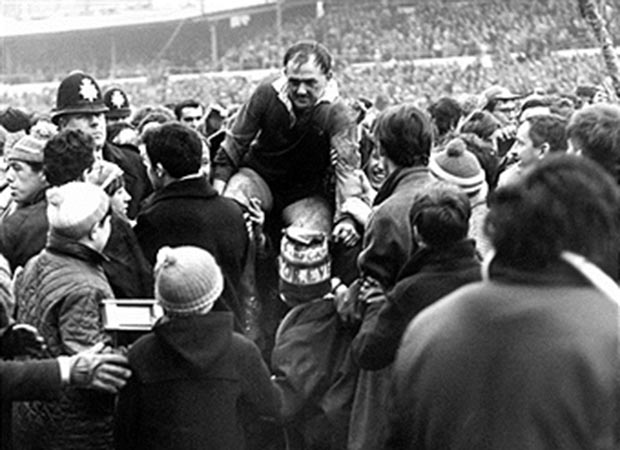

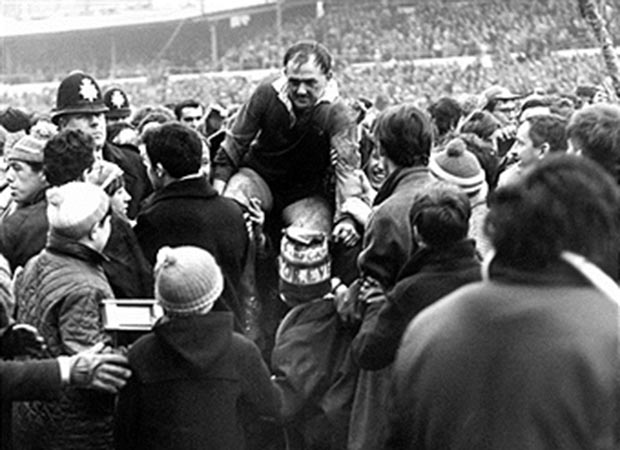

Except, of course, for the sore ones from a back that had to be repaired after Meads ensured the scrum-half’s first exposure to the All Blacks would end prematurely with the Wales

captain being carried off, not aloft on the shoulders of jubilant team-mates but flat out on a stretcher.

What happened on the last Saturday before Christmas in 1963 has been lent a certain relevance if not topicality by an event at Cardiff Arms Park last Wednesday night. Rowlands had returned to the scene of the crime, or as close as he could without being soaked to the skin, to collect a Lifetime Achievement award from the Welsh Rugby Writers’ Association at their annual dinner.

Even now, there is nobody in the world game to match his CV – captain of his country on debut, coach, selector, chairman of selectors, manager, committee member and president. Wales under his management finished on the podium at the 1987 World Cup and two years later the Lions, under the same management, beat Australia.

All that tells only half the story of the man himself. At 79, Rowlands still speaks of the game with all the missionary zeal of a revivalist preacher and recalls the motivational talks of yesteryear as if he’d given them last week which makes him a cross between Evan Roberts and Bill Shankly.

He was, to coin Sir Clive Woodward’s maxim, ‘smarter than the average bear’ – so smart that the Wales team he coached from the late Sixties to mid-Seventies nicknamed him ‘TC’, as in Top Cat, then a popular cartoon television series about an scheming pack of Manhattan alley moggies.

Rowlands set trends almost wherever he went. His merciless bombardment of the touchline at Murrayfield in 1963 forced the game to outlaw direct kicks to touch between the 25s as they were referred to in pre-metric times. His innovative brand of team-talk made him famous before anyone on this side of the Atlantic had heard of Vince Lombardi and the Green Bay Packers.

He may not care to be reminded that in calling a mark against New Zealand and Meads inflicting a more lasting one, Rowlands, pictured below, unwittingly initiated the longest-running trend of all. Wales had never lost to the All Blacks in Cardiff until then and they haven’t beaten them anywhere since.

“They launched an up-and-under and I marked it legally. Unfortunately I’d turned my back so I didn’t see Meads coming through from an offside position. His knee caught me in the back, I was paralysed for a short period and then years later I had an operation for the fusion of a lumbar disc.”

A similar incident today would provoke calls for a red card. Meads’ version of what happened created an impression that he could play fast and loose with the laws knowing most referees would turn a blind eye rather than dare rock the Establishment boat by sending him off.

“I didn’t punch the wee man,” he said. “What happened was that Clive was yakking and kicking the ball, yakking and kicking. Wales had bugger-all backs in those days so they kicked it all day.

“And then our man (Kevin) Briscoe put up an up-and-under. I had a five-yard start, Clive was under it and I got the little bastard. Ran right over the bloody top of him. He put on a good act, 80,000 people booed me and all I did was knee him up the arse. God, the memories are good.”

Not as good as Rowlands’, unique among Welsh coaches in that he really liked the reporters he worked with in his pomp. In his acceptance speech he singled them out one by one, most notably the late Dennis Busher then of the equally late Daily Herald.

“I’ll never forget his kindness on the night I first got selected for Wales. Dennis had a telephone card which meant you could make a call without pumping coins into a black box. Thanks to him I was able to ring my mother and tell her I was in.”

Imagine that happening today. Imagine, too, the captain of Wales being woken up at two o’clock on the morning of a match at Murrayfield by a few friends from back home. That happened to Rowlands in Edinburgh a few months before Meads hit him for six.

Rowlands’ pal, Idris Jones, had driven through the ice and snow of that Arctic winter of ’63 from Upper Cwmtyrch in the Swansea Valley to the Scottish capital. Jones went straight to Rowlands’ room, apologised for the lateness of the hour and assured him ‘we’ve just arrived, safe and sound’.

“That meant something very special to me,” Rowlands said. “Idris always said that whatever the weather, we’d be there to support you and five of them had driven all that way in awful conditions. Far from being annoyed I was delighted to know they’d arrived.”

For all the trophies he has won, there have been times when he felt badly let down, bad enough to resign, albeit temporarily, as WRU president in protest at what he saw as betrayal by colleagues who defied Union policy and accompanied a rebel group of Welsh internationals on their visit to apartheid South Africa in 1989.

There was the equally shameful sight of Welsh players scrapping among themselves in the dining room after their 63-6 hammering by the Wallabies in 1991 and of Rowlands, the appalled manager, trying to impose some law and order.

The regrets, as Frank Sinatra would say, are too few to mention and all rather trivial compared to the triple tragedy of losing your father, one sister and brother by the age of ten followed decades later by the trauma of fighting cancer. Rowlands is still going strong.

Not so much a legend, more a national treasure.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login