Billy Boston now has a life-sized statue of his very own in Wigan, a bronze creation for which the town clubbed together to raise £90,000.

Billy Boston now has a life-sized statue of his very own in Wigan, a bronze creation for which the town clubbed together to raise £90,000.

Its unveiling last week came almost exactly a year after a similar ceremony at Wembley Stadium, outside Gate G where the Welshman can be seen frozen in his pomp in a group statue alongside four other all-time Rugby League greats – Martin Offiah, Alex Murphy, Eric Ashton and Gus Risman.

Boston deserves no less, not that he would ever consider himself worthy of one public monument, never mind two. A man of unfailing courtesy, he has never forgotten where he comes from and where it all began, in what used to be Tiger Bay.

And that begs a question. Why, when Wigan and Wembley have seen fit to immortalise Boston, has the city of Cardiff done nothing by way of granting similar recognition to one of its most famous sons?

Those unconvinced about his worthiness need only acquaint themselves of one fact, that Boston holds a record which will never be broken. Over a period of almost 20 years from the Fifties to the early Seventies, he scored more tries than any other British wing in League or Union – 478 in almost as many games for Wigan, 521 all told.

Boston never wanted to leave the Bay in the first place and his friends have argued, with ample justification, that he would have stayed there had Cardiff Rugby Club not ignored him. It wasn’t as if they hadn’t heard of him because Boston’s teenaged exploits at junior level had been publicised locally.

When he did manage to put in a fleeting appearance at the Arms Park, in September 1951, it was no thanks to those running Cardiff RFC. Instead he lined up for Cardiff & District, a team drawn from the city’s junior clubs, in what used to be the traditional opening fixture.

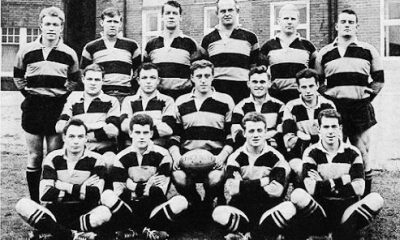

Our photograph, unearthed by rugby historian Howard Evans and published for the first time, shows the 17-year-old W Boston sitting, arms folded, in the middle row. The son of a father from Sierra Leone and a Welsh-Irish mother, he was allowed to go his own way without a word of encouragement.

“As a Cardiff boy I wanted to play for Cardiff but I didn’t achieve it,” he told me. “I never thought I was welcome. There you are…

“They didn’t pick me and I think it was all to do with colour which was why I wasn’t welcome. I wasn’t the only one. There were other terrific young black players in Cardiff around that time. They were all good enough to play professionally. So why weren’t they good enough to play for Wales?”

Three names spring to mind – Clive Sullivan, Colin Dixon and Johnny Freeman. “You couldn’t play for Cardiff in those days if you were black,” Freeman said in the book Triumph and Tragedy. “Nobody ever said as much but that was the way it was. If they ignored Billy, what chance did the rest of us have?”

Despite the snub, Boston still had his heart set on finding an alternative way into the Wales team when Wigan chairman Joe Taylor and vice-chairman Billy Gore knocked on the door of his home at No. 9 Angelina Street in March 1953. Taylor opened his briefcase and spread £1,500 in white five pound notes on a table in the front room.

“I’d never seen so many notes in all my life,” Boston told me. “My mother didn’t bat an eyelid. I looked at her as if to say: ‘How are you going to get me out of this?’

“I took her out of the room and told her: ‘I don’t want to go anywhere. Get rid of them.’

“She said: ‘I’ll get rid of them allright, son. Leave it to me.’

“So my mother went back into the front room where the Wigan directors were waiting. ‘Give me £3,000,’ she says. ‘And he’ll sign right away.’

“I thought that was a clever way of getting rid of them. There was no way they were going to stump up that much. I’d left the room because I wanted to stay in Union and see how far I could go.”

Wigan acceded to Nellie Boston’s demand, doubling their offer on the spot. “They got the contract out and my mother said: ‘I’ve given my word. You sign that. I signed it and then I thought: ‘What have I done…?’”

Like those before and after him, Boston fell victim of the shameful apartheid as imposed by Union during the cold war with League. All too soon he would be barred from the clubhouse at the Arms Park as a petty reprisal for turning professional.

True to form, the man who didn’t want to leave has never been slow to go back, after all these years as arguably the most revered living Wiganer of all. He is one of the few inductees of the Welsh Sports Hall of Fame to attend the annual dinner, a pilgrimage he makes even now in his early Eighties with his wife Joan.

Cardiff as a city ought to have paid him a suitable tribute long ago, akin to those erected for Gareth Edwards and the world flyweight champion ‘Peerless’ Jim Driscoll. They need to do something to show the world that Boston is a prophet with honour in his own land.

Time is not on their side.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login