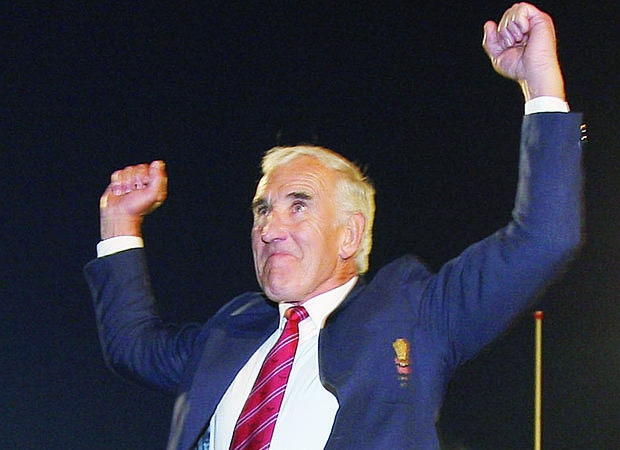

More than 40 years have come and gone since the day the pubs ran dry in Llanelli and Delme Thomas still stands alone, a defiant figure in the lop-sided history of Wales and New Zealand.

More than 40 years have come and gone since the day the pubs ran dry in Llanelli and Delme Thomas still stands alone, a defiant figure in the lop-sided history of Wales and New Zealand.

Four decades on, he is still the last captain of a winning Welsh team against the All Blacks which makes him not just an enduring symbol of the Scarlets‘ finest hour but also a constant reminder of recurring Welsh failure.

There is always a chance, no matter how remote, of Sam Warburton replacing him on Saturday night at what will be the 34th attempt by a Welsh team to beat one from New Zealand since the tricks and treats of Hallowe’en at Stradey Park in 1972.

That the previous 33 since then have all gone the same way hardly gives any genuine cause to imagine next Saturday’s will be any different. Maybe the technicians running the Wales camp should ignore the scientific approach and give their players a pre-match drink of sherry and two raw eggs.

Thomas, an electricity board linesman who would be back at work climbing telegraph poles as normal the morning after, knocked back his favourite matchday tipple just before he went to work on the All Blacks. Two of the younger players who idolised him, Ray Gravell and Gareth Jenkins, did likewise.

How Llanelli beat Ian Kirkpatrick’s team all those years ago has long since passed into folklore, the meticulous preparation of their cerebral coach, Carwyn James, and Thomas’ famous speech when he said he would willingly trade everything he had achieved with Wales and the Lions for victory that day “on our own ground in front of our own people”.

It flooded the team room at the Ashburnham Hotel with such emotion that a young Phil Bennett found himself reduced to tears. All that has been lionised in words and song by poets and troubadours.

What has not been documented is Thomas’ private struggle against depression, at least not until now. He gives chapter and verse in Delme, The Autobiography with Alun Gibbard, newly-published by Y Lolfa.

Thomas, happily hale and hearty again at 72, is in no doubt that his illness can be traced back to the day he hung up his boots in 1974 and tried to begin a new life away from the Scarlet brotherhood.

“It may well be a cliché but you did become a family,” he says. “Leaving that family proved to be a traumatic experience. It affected my health. It affected my whole personality.

“Something had been taken away and it left a huge gap in my life. I wasn’t ready for it and it hit me really hard. By the early 1980s I’d got to the point where I’d lost interest in life completely. I didn’t want to see anyone or go anywhere.

“I suffered a nervous breakdown. I was admitted to hospital and stayed there for weeks because my feelings had sunk so low.

“One thing that’s clear to me now looking back at such a difficult period in my life is the fact that I didn’t want to admit that I was in the state I was in. And I don’t mean that I just didn’t want to admit it to other people. I didn’t want to admit it to myself either.

“It was extremely difficult to concede to yourself that you were suffering because, quite simply, it would be considered a weakness. When I ended up in hospital, I hated the fact that I’d been admitted for such a reason – a mental one, not a physical one.

“I refused to accept that I was in the psychiatric ward of a hospital. It would have been far easier for me to come to terms with being a patient on one of the other wards, the ones where patients had illnesses that other people were far readier to accept.

“I can see quite clearly now that the biggest mistake people make with any sickness of the mind or emotions, is refusing to accept that you have it in the first place.

“So what was pressing down on me so heavily that it stopped me facing up to how I really felt? What was someone who’d been involved so successfully in the world of rugby doing lying in a hospital bed, in a psychiatric ward.

“I wasn’t much of a British Lion in there, was I? I felt I’d let my family down. I’d failed as far as they were concerned. I’d failed as a father and a husband. The pressure was unbearable.”

Thomas reveals how a chapel minister, the Reverend Glyndwr Walker, helped him along the long road to recovery. “There are still some days when I feel low in spirits,” he says. “But I’ve learned how to deal with that now. The only mark left by my illness is that I don’t like walking into a room full of strangers on my own. That wasn’t the case before.”

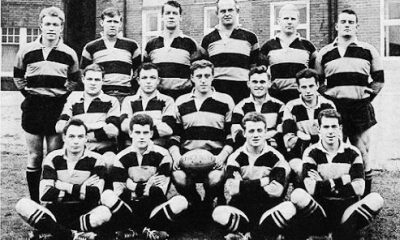

A Lion before Wales got round to capping him, Thomas toured New Zealand twice, in 1966 and 1971. Colin Meads gave him a traditional welcome in the shape of a big right hand which left his young challenger from faraway Bancyfelin requiring dental treatment.

Thomas bided his time. Five years later, he played in three of the four most famous Lions’ Tests of all, including the last one at Eden Park which brought Meads’ monumental career to a losing end. Delme had counted him out.

*This article was first published in The Rugby Paper on November 16.

2 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment Login

Leave a Reply

Cancel reply

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Latest News

Super Rugby Americas: Round Ten Review

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions: Biggest winners and losers from Andy Farrell’s selection

Pingback: auto swiper

Pingback: พรมรถ