Freddy ‘Tanky’ Turner captained Scotland one hundred years ago, a Liverpudlian by birth who worked in the family printing business and played cricket for Lancashire’s second XI.

Freddy ‘Tanky’ Turner captained Scotland one hundred years ago, a Liverpudlian by birth who worked in the family printing business and played cricket for Lancashire’s second XI.

Percy ‘Toggie’ Kendall had been England‘s scrum-half a few years earlier, a solicitor who captained Cheshire against the original All Blacks only for the war to finish his voluntary work coaching youngsters at Birkenhead Park.

Turner and Kendall would have greeted the advent of 1914 like any other New Year. The Welsh selectors gave David Watts more reason to celebrate than most, its arrival coinciding with the Maesteg coalminer’s first cap, against England at Twickenham.

The new hooker began the championship in a pack that would finish it known as ‘The Terrible Eight,’ a nickname that reflected a tendency to take the law into their hands whenever they felt necessary. The Ireland match in Belfast, the last home international before The Great War, has been described as a running fist fight during which Wales outpointed their opponents 11-3.

A few weeks later against France in Paris, England won the Grand Slam under the charismatic command of Ronnie Poulton-Palmer, a three-quarter whose mesmerising effect on opponents moved one to say: “How can you stop him when his head goes one way, his arms another and his legs keep straight on?”

By the end of that mis-match at Colombes, the England captain reduced the French to such a state with four tries of his own that they didn’t know whether they were coming or going. Like Turner, Kendall and Watts, Poulton-Palmer would never play for his country again.

A year that marks the centenary of the start of “the war to end all wars” puts their fate, along with those of countless millions more, into poignant focus. What happened to four of the 128 international players who made the supreme sacrifice, as enumerated by my colleague Brendan Gallagher in these pages on Remembrance Weekend, is worth recalling lest we forget.

Turner (26) and Kendall (34), ‘Tanky’ and ‘Toggie,’ had much in common. They were born and raised on Merseyside, they commanded men on the Western Front and they fell to a sniper’s bullet within two miles and 11 days of each other in January 1915.

And they have lain side by side ever since in the corner of a Flanders field, buried in Special Memorials 13 and 14 at the churchyard in the Belgian village of Kemel:

Lieutenant Frederick H Turner, 10th (Scottish) Battalion, The King’s Liverpool Regiment, 166th Brigade, 55th Division.

Lieutenant Percy Dale Kendall, 10th (Scottish) Battalion, The King’s Liverpool Regiment, 9th Brigade, 3rd Division.

Turner, whose moniker ‘Tanky’ had nothing to do with his tragically brief military service and everything to do with his scrummaging power on the rugby field, died in the same area of the second battle of Ypres where Corporal Adolf Hitler fought for Germany.

If only the budding megalomaniac had been sacrificed instead, how different the 20th century would have been. Turner’s last moments are recorded in a letter written by a fellow officer and reproduced in the book, Cameos Of The Western Front, by Tony Spagnoly and Ted Smith.

“After breakfast on 10 January 1915, he (Turner) went down to the trench to look at the barbed wire he had put out in front the night before. On the way he looked up twice for a second and each time he was shot at but both shots missed.

“He then got to a place where the parapet was rather low and was talking to a sergeant when a bullet went between their heads. Lieutenant Turner said, ‘by Jove, that has deafened my right ear’.

“The sergeant remarked, ‘and my left one too, sir’. He (Turner) went a shade lower down and had a look at the wire and was shot clean through the middle of the forehead, killing him instantly. They carried him almost three kilometres to the Kemel churchyard.”

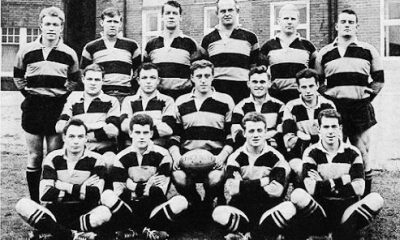

The Scotland-England match at Murrayfield next month marks the 100th anniversary of the last pre-war Calcutta Cup match in Edinburgh, at Inverleith where the visitors edged it 16-15. Of the 30 players that day, 13 would be killed in action.

The Scots lost seven – full-back Billy Wallace, right wing John Will, left wing James Huggan, scrum-half Eric Milroy, second row Andrew Ross, No. 8 Eric Young and the hooker, Turner.

Six English players perished – left wing Arthur Dingle, centre James Watson, scrum-half Francis Oakeley, second row Alfred Maynard, No.8 Robert Pillman and the captain, Poulton-Palmer, killed by a sniper’s bullet at Ploegsteert Wood four months after Turner and Kendall had suffered the same fate.

Watts, the newly-capped Welsh hooker, was killed on the Somme the following year, July 1916 five days after Pillman perished in the same battle. The Maesteg miner, whose body was never recovered, played in a pack of unrelenting ferocity led by, of all people, a clergyman, the Rev Jenkin Alban Davies, from Aberaeron.

Asked if he had ever been offended by some of the more colourful language flying around him, Davies, a chaplain in the Royal Field Artillery who lived to the ripe old age of 90, said: “I always wear a scrum cap.”

The unimaginable carnage of 1916 claimed the lives of four more Welsh internationals, among them Louis Phillips, the Newport fly-half who had won the Wales amateur golf title for the second time in 1912.

Dave Gallaher, captain of the pioneering All Black invincibles of 1905, also lies among the poppies of Flanders not far from where he fell, in a village whose name has long been synonymous with slaughter on an obscene scale: Passchendaele. An Irishman from Ramelton in Co. Donegal who emigrated with his family at the age of five, Gallaher gave his life at the third Battle of Ypres in 1917, one of more than 600,000 soldiers who died over a period of four months.

When the All Blacks return to these shores in November, they will make another pilgrimage to Gallaher’s resting place in the British War Cemetery seven miles west of Ypres at Nine Elms – Plot 3, Row D, Grave No. 8.

They have, of course, been there before, never more poignantly than in 2000 when they planted a rose called Lest We Forget which had been bred on behalf of the Royal New Zealand Returned Services’ Association in memory of those who never returned.

It would be a crying shame if March 21, the centenary of the 1914 Scotland-England match, were to pass without the Unions arranging a journey to a little village in West Flanders to pay homage to ‘Tanky’ and ‘Toggie’ and the rest.

Lest we forget…

British and Irish Lions

Henry Pollock’s rise to stardom continues with 2025 British and Irish Lions selection

British and Irish Lions

Maro Itoje named British and Irish Lions captain for tour of Australia

You must be logged in to post a comment Login