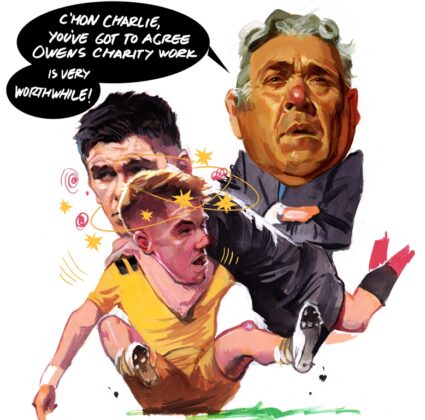

OWEN Farrell’s five-match ban for a head high swinging arm tackle, which rendered the 18-year-old Wasps fly-half Charlie Atkinson unconscious before he hit the artificial turf at Allianz Park last weekend, has put the England captain in the firing line.

Farrell’s tackle was a shocker, not just because he had plenty of time to make a much lower tackle, but also because this is an era in which the dangers of concussion have never been broadcast so loudly. Yet, the Saracens fly-half appeared to be oblivious of the requirement to hit the ball-carrier well below the shoulder line.

While Farrell is a proven matchwinner at the highest level, the incident has fuelled a debate over whether the England captain could become as much of a liability as an asset, which will not go away any time soon.

It demonstrated that Farrell, who is in the prime of his career at 28, is still prone to rushes of blood to the head when he is frustrated – as he clearly was during a match in which a full strength Saracens side was outplayed by a young Wasps B team.

It raises questions about his judgement and temperament, and comes just after a critical observation of his demeanour by Siya Kolisi, the South African 2019 World Cup winning captain. Kolisi said that after the England bus arrived half an hour late at the ground before the final in Yokohama, Farrell’s head appeared to be in such a spin at the coin-toss that he was convinced it would be South Africa‘s day.

When I asked Eddie Jones about this at a Press conference a few days before Farrell’s head-shot on Atkinson, the England coach indicated that it was South African mind games of the ‘winners are grinners’ variety, and indicated that he had full confidence in his choice of skipper.

Jones said: “What qualifies Kolisi to make the comment is that he won and Owen lost. Everyone is always cleverer after you win. I think Owen did a great job in the World Cup and the Six Nations. If he is fit and available for selection there is a very good chance he will be captain.”

What was concerning about the tackle on Atkinson is that there were no mitigating factors. The only adjustment that Farrell made came after he pole-axed the Wasps youngster. He accepted culpability instantly, offering no verbal plea when shown the red card by referee Christophe Ridley, and then waited on the touchline for the stricken Atkinson to be revived before apologising to him as he made his way to an HIA assessment.

It was an adjustment which was as well-judged as the tackle before it was indefensibly ill-judged. Although Farrell will have been aware that his chances of representing Saracens in their away European Cup quarter-final against Leinster in Dublin were cooked, his actions after being sent off suggested he already had mitigation in mind given the potential threat to him representing England in the final round of the Six Nations, and the Eight Nations thereafter.

Farrell has great strengths, having developed into one of the best pressure goal-kickers the pro game has produced. He is also as an outstanding playmaker and distributor, but the part of his skills-base that does not come close to the same high standards is his tackling.

The England captain’s tackle technique and timing are exposed too often for comfort, as is his penchant, following his formative years in Rugby League, of targeting the ball-carrier with a rising shoulder to the chest in a straight-on tackle to dislodge the ball. He often uses a swinging arm to do the same when making a cover tackle, as Atkinson discovered to his cost.

This week Will Greenwood, who had his own defensive difficulties as a player, described Farrell’s tackling as, “a work in progress”.

While it is true that the greatest players never stop learning and improving, Farrell has so far completely failed to eradicate his default position, which is to make the chest-high ‘hits’ he learned as a youngster in League, usually without gripping with his arms. The hazard is that these shoulder strikes frequently ride up to make contact with the opponent’s neck or head.

It is imperative he replaces it with a much lower trajectory tackle between waist and knee in which arm-grip and leg-drive are the key components, because from now on Farrell is a marked man who will attract greater scrutiny from referees.

Following Farrell’s controversial head high/no-arms collisions in the 2018 autumn series against South Africa and Australia, there was a sense, both at home and overseas, of him getting out of jail.

Farrell’s uncensored escape after a last-minute rising shoulder strike on Springbok centre Andre Esterhuizen meant England hung on for a 12-11 win at Twickenham. Another unpunished no-arms shoulder strike on Australian lock, Izack Rodda, which prevented a Wallaby try which would have given them a half-time lead, saw salt rubbed into southern hemisphere wounds – especially as Farrell then created a try for Elliot Daly which saw England romp to victory.

Since then, Farrell has become something of a target himself, with dangerous high hits on him at the 2019 World Cup earning Argentina lock Tomas Lavanini and USA flanker John Quill red cards, indicating that there is a desire to pay him out in his own coin.

However, being a sometime victim did not stop widespread outrage on online forums about the leniency of the five-match ban served on the England captain by an RFU disciplinary panel.

What had no place in the disciplinary process was the idea put forward by the panel that Farrell’s charitable work somehow has a material influence in mitigating the red-mist recklessness of his challenge on Atkinson. It has nothing at all to do with his actions on the pitch.

The same applies to the glowing character references the panel heard from Jones and Saracens DoR Mark McCall, given that both coaches have a vested interest in Farrell receiving the shortest possible ban.

The mood in South Africa suggests Farrell is already in the process of being demonised in the build-up to a 2021 Lions tour.

The giant former Springbok enforcer Bakkies Botha did not take long to pipe up online, mentioning a nine-week ban he served for a head-butt to the back of Jimmy Cowan’s head after the All Black scrum-half had held him back by the jersey.

The South African lock, who fittingly owns a butchery business these days, said: “If he had a 4 on his back and his surname is Botha he would get a ban for just after the Lions tour next year. If it was about timing my timing was out on Jimmy Cowan as well.”

RFU disciplinary panels cannot be seen to have one set of rules for high-profile figures like the England captain, and another when a bloke from the Pacific Islands makes a high hit with a swinging arm.

They may find that a 50 per cent reduction in tariff is not a strong enough stand, and that it boomer- angs back on them – and on Farrell.

NICK CAIN