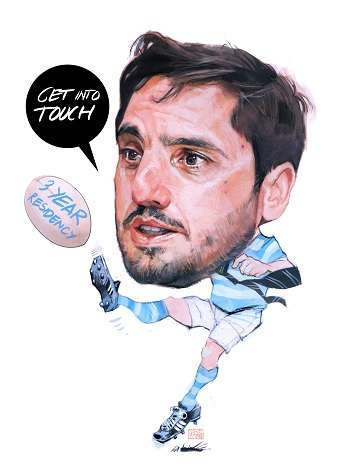

Pichot, whose rise through the ranks of the Argentine Union has not been without controversy, has made a good start by highlighting a flawed residency qualification which will cripple the international game if it is left in place.

I have always argued that three years is far too short a time frame to stop international “marriages of convenience” which, increasingly, have seen promising players from developing Tier 2 nations plundered by the big powers.

We all know that this trafficking in players – especially from the Pacific Island nations – is almost exclusively down to economic factors, and that there is barely a top eight country without a Fijian, Samoan or Tongan in their ranks.

The same, ironically, is now true of one of the world game’s biggest traditional powers, with South Africa’s economic downturn, and government enforcement of transformation policies in sport, seeing their players being adopted by countries around the world.

However, by encouraging a mercenary market at Test level the three-year residency ruling is damaging not only the “exporting” country but also the host nation.

Playing numbers, and the profile of Rugby Union, plummeted in Scotland when the SRU gave the green light to imports from the Southern Hemisphere in the late 1990s. An influx of “kilted kiwis” undermined the domestic structure with promising young Scots finding their path to top honours blocked by imported players – most of whom returned to New Zealand when their Scotland contracts ended.

The flip side is that nations like Fiji, Samoa and Tonga have been hobbled in their attempts to gain a seat at rugby’s top table because they cannot pay their players anything close to the salaries they would get with a Six Nations or Sanzar contract.

Pichot sees the problems, and he wants them tackled by World Rugby extending the residency rule to five years – and he wants it done urgently.

Pichot said of the exisiting residency rule, “I think it’s wrong. Somebody will kill me, but we need to change it. It should be for life. I understand maybe a five-year (qualification period), and I think it will be on the agenda in the next six months.”

He added: “It is very important to keep the identity of your national team. It’s a cultural thing and an inspiration to young kids. When you have on your team all players who haven’t lived in the country that they represent, it’s not great.”

Pichot said there was a moral issue at stake. “There are special cases when people move when they’re ten years old. But going back to when a player is taken, like they are doing now, from an academy in Tonga and putting him to play, say, in an Ireland shirt, it’s not right.”

Pichot also raised the issue of salary differentials. “I would love him to play for Tonga, to make money in Tonga, and live well. When I see the national anthem and people not singing it, it confuses me a little bit.”

It’s encouraging to hear such forthright language from a young World Rugby administrator with a desire to fix a problem that has festered too long.

However, I would urge Pichot to go for a seven-year residency period, because that’s the key to stopping the trafficking in teenage Pacific Islanders by Top 14, Premiership, and Pro 12 talent scouts.

They are much less likely to take a gamble on a 13-year-old than a 16-year-old because they are harder to assess at the younger age. Hole the trade below the waterline by banning any European, Australian or New Zealand academy or school from having any overseas rugby imports who are not 16 or over. Reinforce that with a seven-year residency period – which means they will be 23 before they can win a first cap – and the trafficking will be curbed.

Combine this with World Rugby-controlled funding to Tier 2 nations which means that their international wages are on a footing with those in the Six Nations and Sanzar, and the international poaching problem will shrink rapidly. At the same time, the base of competitive Test nations will grow.

Miscellaneous

The Best Rugby Themed Games

Features

OSCAR WILSON

You must be logged in to post a comment Login