The referral system, whereby a referee can ask the TMO to review footage and adjudicate on whether tries have been scored, or foul play committed, is riven with inconsistency. As a result, powerful voices have been raised against it, with the Saracens chief executive Ed Griffiths among the most vociferous.

Griffiths has argued that the £800,000 spent so far on the system by the Premiership is a waste of time and money. Griffiths articulates the views of many rugby fans when he says: “The flow of the game is ruined, the spectator is irritated and often bewildered as to who has made the decision, and we have undermined the authority of the ref – and all for what?”

Griffiths’ view is that the referee is still best placed to make judgements on the field because so much of the television replays still require him to make a judgement call. However, he says that instead of it being simply his decision, he is now open to influence from television producers and commentators.

The Saracens man has his own axes to grind given that two TMO decisions went against his club in last season’s cliffhanger Premiership final against Northampton and cost them the title. The first came when Owen Farrell was denied a try by the referee (JP Doyle) after the TMO had awarded it, and the second when the Saints were awarded a last-minute Alex Waller try, which was given by the TMO but not, initially, by the referee.

It is hard to disagree with Griffiths’ conclusions, not least because barely a weekend of professional rugby goes by without there being disputed calls which undermine the officiating system.

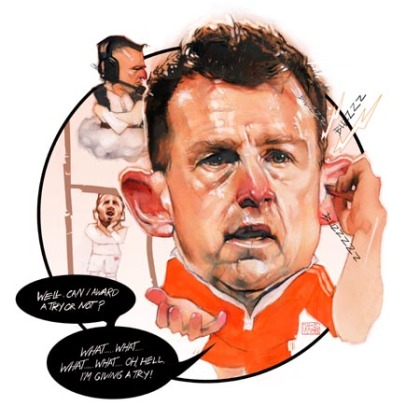

Last weekend the Kiwi referee Glen Jackson was in the TMO spotlight when he was in charge of Ireland‘s Test against Australia in Dublin.

As Australia hauled themselves back into the game before the interval they scored a disputed touchdown through fly-half Brendan Foley. The incident in question was whether the scoring pass to him from scrum-half Nick Phipps had gone forward, which to the naked eye appeared to be highly likely.

As Jackson struggled with the inadequate communications system between himself and the TMO – having to clap his hand over one ear in order to get some clarity through the crackling static on the one fitted with an earpiece – the lack of professionalism was laid bare.

The same applied in the England v New Zealand game when Nigel Owens came under fire for a series of controversial TMO calls. It started when he awarded Aaron Cruden a debatable try without referring it to the TMO. Dissatisfaction in the crowd intensified towards the end of the second half when he gave a try to Charlie Faumuina, and was then involved in a desperate post-facto debate with the TMO in which neither could hear the other above the crowd noise and static.

Television companies do not invest the money required to make the TMO system as failsafe as it can be. To do so requires a big spend on cameras, cameramen and technicians, because it is they who ultimately provide the multiple camera angles required for the TMO to eradicate doubt.

The American broadcasters covering NFL deem it worthwhile to make that investment, whereas their rugby counterparts in the UK, and elsewhere, do not – or at least, not at the moment.

By the same token rugby administrators within the IRB, the Home Unions, and the Southern Hemisphere, have to recognise that the whole system requires standardising as well as serious investment.

This means the same number of cameras, and camera angles, at each ground for each match. It also means state-of-the-art communications so that decisions are reached with the same speed, efficiency and clarity as exists in American Football. It means importing a system like Hawkeye in cricket to ensure that the goaline has been crossed by a player and the ball touched down.

There is also the question of ensuring that host broadcasters and TV producers do not wield undue influence on the TMO, or disciplinary procedures, by withholding footage, or being biased in selection of live or post-match replays.

The pitfalls are clear, with the All Black coach Steve Hansen complaining that repeated big screen replays of Dane Coles, kicking out with his foot during the match against England, influenced his hooker being sin-binned.

Another question mark was that over the crucial try awarded to the South Africa centre, Jacque Fourie, during the epic 2009 series clincher against the Lions in Pretoria. I have always been perplexed at the lack of a camera angle down the touchline that Fourie crossed, and therefore the inability for anyone to know whether he touched down legitimately or was tackled into touch before he grounded the ball.

The remedy is to appoint an independent television producer to ensure justice in terms of access to footage. However, getting someone to watch the watchers starts to make the system look overblown.

The problem is that there are disputes over TMO calls after almost every match and if it is not addressed by the IRB/World Rugby then the 2015 World Cup stands a good chance of descending into farce and damaging the image of the sport.

The only conclusion is that either the TMO process is properly resourced by broadcasters and the IRB, using existing technology and new innovations to give

television officials the best chance there is at arriving at the correct decisions, or the process is a pointless half-way house. If it is the latter it undermines referees and TMOs by making them look indecisive and, often, incompetent.

Conclusion? Either do it properly or bin-off the TMO before the World Cup.

*This article was first published in The Rugby Paper on November 30.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login