Yet, Premiership Rugby chief executive Mark McCafferty felt he had to give a vociferous defence of the Premiership player development programme. His assertion that all is well because around 70 per cent of the Premiership players are England qualified, is not necessarily as good as it sounds. For a start that means almost a third of all players playing in our best league are not qualified to play for this country, plus, more importantly, he doesn’t clarify what percentage are in the crucial positions of half backs and front rows.

Then there is the fact that ‘England qualified’ doesn’t mean that the players are English or have been brought through the academy system. Under World Rugby rules, players from anywhere in the world who haven’t played international rugby will qualify to play for England after just three years and with the increasing number of foreign players coming to these shores to ply their trade as professional rugby players, the opportunities for home grown talent are limited.

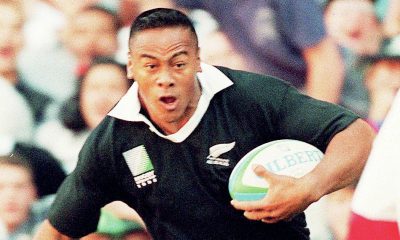

A perfect example is Wasps Nathan Hughes, born in Lautoka, Fiji, who learned his rugby in Auckland before coming to England. He chose not to represent his home country at the World Cup and is now qualified to play for England.

Nathan isn’t the first player to do this and he certainly won’t be the last and there is a distinct possibility that increases in the wage cap will encourage many more young players to make the journey north. In the past, it was mainly the Southsea Islanders who came to seek their fortune but that is all about to change as South Africa bring in quotas for all teams, which will leave a large number of young players with no choice but to leave the country if they wish to pursue their dream.

Many will be young enough to join club academies and unless World Rugby change policies, they will qualify to play for England. And even if they don’t reach the dizzy heights of international rugby, they will play in the Premiership.

McCafferty is right when he says that there is enough young talent coming through, even if it’s not all English, but are they getting enough playing opportunities or, as seems the case, are they either just sitting on the bench or playing for the ‘A’ league team?

Whatever McCafferty says, it is impossible for a senior England coach to give the necessary game time to enough young players for them to develop into senior international players.

The clubs ‘farm’ out young players to Championship clubs so they can achieve game time and develop into premiership players. As the Premiership keep reminding us, the gulf in playing standards between the Premiership and the Championship is vast – meaning that any player development will also be at a lower standard thus reducing the chances of players reaching their true potential, or at the very least, stifling individual development. The stagnation in personal development remains until the Premiership club allows the player to make the transition from Championship to regular Premiership first team.

As so few young players get regular first team exposure, it will always be a gamble for an international coach to pick even the biggest stars of the England Under 20s Junior World Champions team of 2014.

The news that Welsh rugby at grass-root and semi-professional level has an endemic steroid abuse problem will raise concerns on this side of the Severn Bridge. While you would expect the professional game to have a problem as players try to get that ‘edge’ that will get them a contract, the rewards at grass roots would hardly seem worth the cost.

There has always been a culture of payment for play at all levels in Wales, even in the amateur days and that will still be the case now. But the demands for bigger, stronger, faster players is not just limited to the professional elite.

As the senior players have got bigger so have those at grassroots, simply because many of the players are those that failed to make the grade and were discarded by the Welsh equivalent of academies. So few players actually make it to a professional contact I am surprised that the numbers of steroid abuse cases are not higher. The temptation for young players to take something to help them make the grade in professional rugby is immense.

The problem is, having taken something to help once and not got caught there is a temptation to do it again if your performance drops and with so few test in the grassroots game, the chances of being caught are virtually zero.

WRU chief executive Martyn Phillips says the problem in Wales is a social one but somehow I doubt it. If players use drugs and get away with it, it doesn’t take long for the use of steroids to become a part of training culture, a culture that could easily cross the bridge.

In England there are even more disappointed youngsters who fail to make the grade and even more clubs willing to pay for a chance to go up the leagues.

If the RFU don’t take what has happened in Wales seriously, it could happen here.

British and Irish Lions

Unconvincing British and Irish Lions labour to patchy victory over ACT Brumbies

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions: Elliot Daly Silenced the Doubters; Now It’s Time for Owen Farrell

You must be logged in to post a comment Login