Coaches or captains? Who should get the glory, who should take the blame and, who should be the visible face of the team? These are interesting and challenging questions, the answers to which Clive Woodward and Nick Cain disagreed on last week.

Coaches or captains? Who should get the glory, who should take the blame and, who should be the visible face of the team? These are interesting and challenging questions, the answers to which Clive Woodward and Nick Cain disagreed on last week.

Nick’s point that the game on the field should not be unduly influenced by coaches off the field is something that I believe all people (including Woodward) would agree with, but I am not sure that that is what Woodward was asking for.

In talking about ‘beefing up’ the role of the head coach when it comes to media and off-field coaching, even during a match, I don’t think that Woodward was looking for a new role for coaches, or even making a dramatic change to what happens now in rugby or cricket.

Selection is also an area where all would be in agreement in that, although the manager/head coach may take advice from those around him, ultimately he must be the one who makes the final choice.

Where I think that Nick has a point is the continual messaging that takes place through the water carriers and the ever increasing number of people allowed on to the field of play during the game.

It is highly probable that many of the messages will come from the plethora of specialist coaches that now surround the team without much, or any direct, input from the head coach who may be quite happy to allow the game to be played out under the direction of his designated captain and leaders within the team.

Rugby, like most team sports is a dynamic, fast-moving game with many different facets where tactics are a constantly changing feast, particularly in the areas that now require specialist coaching.

Team management has moved on from the days where a manager/head coach, coach, doctor and a physiotherapist were all that was required to run the team, to the level that we have now where there are almost as many off the field as on it!

Each of those specialist jobs may be seen as essential (although I have my doubts) and each will want to make sure that the team understand and follow their instructions (if only to guarantee their job security).

Unlike the head coach, whose task is virtually done when the team take to the field, (he will still have some decisions to make regarding substitutions, though it’s likely those decision will be made in consultation with the specialist coaches and the technology personnel), the specialist coaches work has just begun.

Picking a team is relatively easy once you know what players are available and that will more or less dictate the style of game you play.

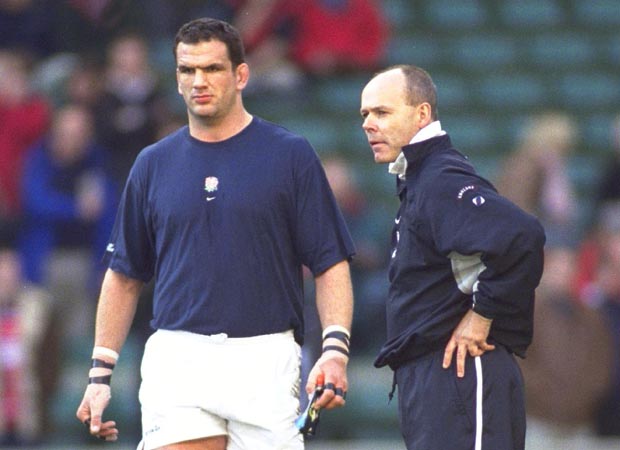

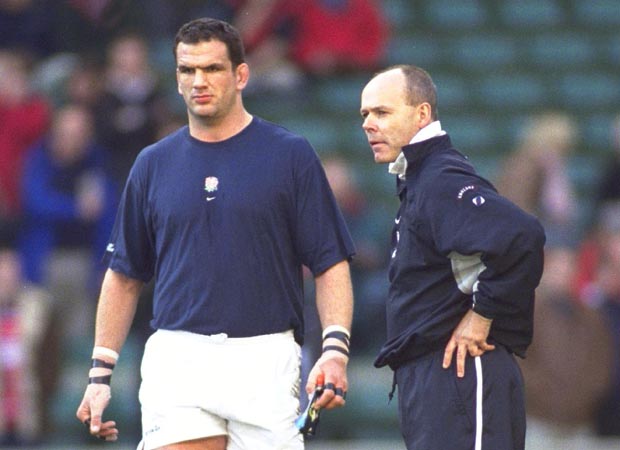

For instance, the 2003 World Cup final side had a dominant pack and the best goal-kicker in the world at the time. Inevitably, the game plan would involve pressuring opponents up front into conceding penalties for Jonny Wilkinson to kick or using a forward platform to create space for a drop-goal attempt.

Once the team had the lead, the opposition would have to take chances, allowing the backs the opportunity to capitalise on pressure induced mistakes.

Selection was relatively easy as long as all the key players (Martin Johnson, Lawrence Dallaglio, Richard Hill, Will Greenwood and Wilkinson) were fit – but for specialist defence coach Phil Larder, it was only when the game had started that he could see if his plan was working or needed adjustment, which it did and resulted in moving Jason Robinson from wing to full-back and full-back Josh Lewsey to wing.

The specialist coaches work on a particular area of the game and those areas, whether defence, attack, scrummage or kicking will be scrutinised by the opposition in an attempt to find weaknesses.

That means the specialist coach must always ‘up his game’ making adjustments to team tactics according to what the opposition do once the game has started.

This is a fairly modern phenomenon and has happened only since the advent of specialist coaches whereas before, players would use their experience to decide when a change in tactics was necessary.

It’s in the area of dealing with the media where I feel both are wrong because, like it or not, whoever is chosen to represent the face of the team at media briefings, the players and particularly the captain, will be the centre of reports, positive or negative, when it comes to the games.

The gladiatorial nature of sport demands that those competing take the limelight, so even if you are the best coach in the world once the team/sportsman take to the field you become irrelevant.

Responsibility or blame, rather like selection, always lies with the head coach eventually. Initially, it falls on the players and some will be made to, as the judge would say, ‘carry the can’ should the team lose, as the coaches seek to ‘pass the buck’. But if failure persists, the head coach will suffer ridicule (who can forget Taylor the turnip head) and is then replaced.

Interestingly, sometimes the majority of the squad stay intact despite a change in head coach, and can with greater experience, become a winning side but little or no credit will be given to the head coach who first picked the players.

As for glory, well again like selection, ultimately it is the head coach who gets it. Alf Ramsey and Clive Woodward received knighthoods almost overnight for their teams winning the World Cup in their respective sports but the players from 1966 had to wait years before receiving any form of official recognition.

In reality, head coaches make most of the decisions off the field and the most important one is selection, which, if he gets it right will leave a lot of leaders on the field to help a chosen figurehead (the captain) that everyone outside the team seem to need.

*This article was first published in The Rugby Paper on August 10.

British and Irish Lions

Charlie Elliott: The 17 backs I would select for the British and Irish Lions

You must be logged in to post a comment Login