The alarm bells started ringing loudly, for me anyway, in a dusty classroom at Loughborough University last May. It was just before England jetted off on their demanding summer tour of New Zealand, but I had travelled to Loughborough to prepare a preview feature on the England U20 team, which was heading in the same direction to defend their Junior World Championship.

The alarm bells started ringing loudly, for me anyway, in a dusty classroom at Loughborough University last May. It was just before England jetted off on their demanding summer tour of New Zealand, but I had travelled to Loughborough to prepare a preview feature on the England U20 team, which was heading in the same direction to defend their Junior World Championship.

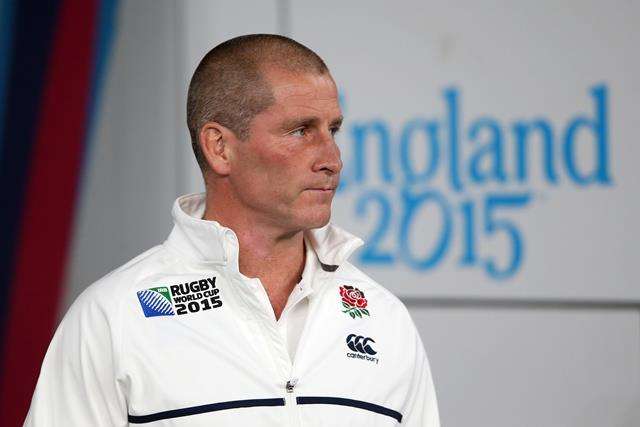

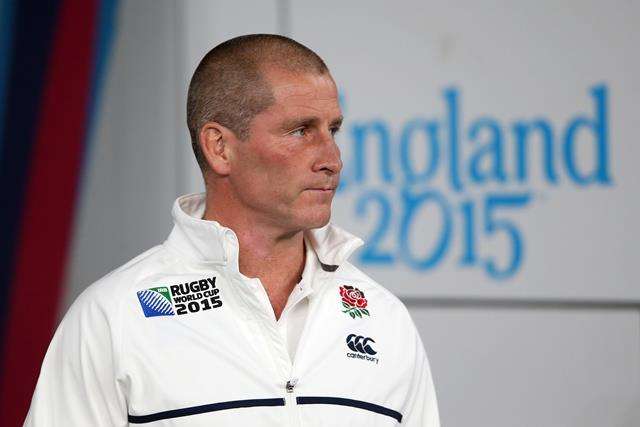

To my surprise, Lancaster was there spending a day with the young tyros and seemed to be enjoying himself massively. In fact, it was the last time I saw him relaxed and smiling. Being a thoroughly decent chap he agreed to do an interview and, as we adjourned to the classroom, he informed me that in the last week or so he had also spent similar time with the England Seven as they prepared for the London Sevens and the England Women‘s squad ahead of their World Cup campaign.

Hold it right there! Lancaster’s England were jetting off to Auckland in a week’s time with a denuded squad for the first Test because the RFU would neither stand up to the Premiership clubs nor the NZRU, and he was concentrating his efforts on England U20, the Women and the Sevens squad? Fiddling while Rome burned.

Coaching England is one of the biggest jobs in world rugby. It’s why you get paid £400,000 a year plus bonuses. Winning the next game and then the game after that should occupy your every waking thought. Your total focus has to be on the here and now, fighting those battles you need to win today, not tomorrow.

Yet here was the England coach, on the eve of a three-Test tour of New Zealand and the most important stage of their evolution rather obviously returning to his comfort zone, the world he knew best.

When faced with something we are not comfortable with and feel might be beyond us, the strong temptation is to busy ourselves doing something else – something comforting – at which we excel. Very well paid elite sports coaches, however, must resist that.

Lancaster was a recent RFU Academy manager, his passion is player development and that is where his skills are best employed. At Loughborough, Lancaster reeled off the talent coming through at U17 and U18 levels like a proud parent.

Lancaster was a recent RFU Academy manager, his passion is player development and that is where his skills are best employed. At Loughborough, Lancaster reeled off the talent coming through at U17 and U18 levels like a proud parent.

Subsequently, it became painful hearing him talk constantly about 2019 and the great young players coming through and the need for all of them to earn a certain number of caps. He was ignoring, and at best sidestepping, his responsibilities to deliver now and at times his approach undermined those whose best shot ever at a World Cup would be a home tournament in 2015.

The RFU had ridiculously and ruinously added a nebulous elite player development role to his job description. No one man could undertake those two roles and certainly not Lancaster, who is no visionary and whose rugby achievements are modest.

The England coach cannot be getting involved in all this periphery business. All he needs to know is that there is a conveyor belt of top players coming through.

Lancaster’s confidence and competence ebbed painfully away when he needed it the most. The New Zealand tour was a massive lost opportunity. All the big basic selections – and cullings – needed to be done there so England’s core 23 had an autumn and Six Nations campaign to gel and develop. The knock-on effect of not doing that was the selectorial confusion of this summer

He wantonly refused to give Danny Cipriani a single minute starting time at fly-half; Freddie Burns came and went; Manu Tuilagi was played on the wing in New Zealand but Anthony Watson couldn’t make the Test team; the need to at least try an openside like Matt Kvesic was not acknowledged; he refused to annoy his employers and go into bat for the likes of Steffon Armitage or even a Toby Flood; he got hideously seduced by the notion that Sam Burgess could suddenly become a world-beating rugby player; George Ford was discarded when England most needed his class. And so on…

The Burgess affair was Lancaster’s nadir and will haunt him forever. This honest man who had preached trust, loyalty, togetherness as a team, culture, reverence for the shirt on all occasions and those heroes who have worn it through the decades suddenly seemed to bin all of that for what amounted to a vanity project.

Luther Burrell, Kyle Eastmond and others had earned the right to be treated equally and given a fair trial but became little more than roadkill in the drive to select ‘Slammin Sam’ – who was so poor for England Saxons in January that the project should have been terminated there and then.

The man who set so much store by the development pathway, the England system – U20 training camps at Loughborough – turned his back on everything he believed in. It was wildly out of character and mystified many in and outside the camp. Even now, as the dust settles, we are left shaking our heads.

United Rugby Championship

Vaea Fifita’s commanding presence has Scarlets pushing for URC play-off spot

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions Watch: Caelan Doris confirmed to miss the tour with injury

You must be logged in to post a comment Login