It’s all a bit rock’n’roll for Bakkies Botha at present. Farewell gigs in Cape Town, Tokyo and, most recently, at the Olympic Stadium in London, while by popular demand an extra date is likely to be added at Twickenham in November when there are plans to reunite him with Victor Matfield for the Barbarians game against Argentina.

It’s all a bit rock’n’roll for Bakkies Botha at present. Farewell gigs in Cape Town, Tokyo and, most recently, at the Olympic Stadium in London, while by popular demand an extra date is likely to be added at Twickenham in November when there are plans to reunite him with Victor Matfield for the Barbarians game against Argentina.

As ‘retirements’ go it’s been pretty full on but, after that final swansong with his old second- row mucker, Botha will execute well laid plans to disappear off the face of the sporting earth – which is some conjuring trick when you are 6ft 7in and 20st and instantly recognised around the rugby globe.

His game farm up on glorious Waterberg mountain in the Limpopo region of Northern Transvaal awaits his full attention, along with his family, and he has sworn off any involvement with rugby other than supporting his son’s high school team.

No media, no coaching or management, no commitments – nothing other than shouting on schoolboy touchlines and the occasional leisurely trip down to Pretoria or Johannesburg to watch the Boks as a fan in the stands.

“Many retired players have this urge to ‘give back’ to the game but the people I need to ‘give back’ to are my family and friends. There is so much travelling and the involvement in professional rugby is so total that it takes you away from your loved ones way too much. At the end of my career the debt I owe is to them.

“Of course, I will help out occasionally with my son’s team like any father would, but I will never be going back to a

situation where there is an expectation, or need, for me to attend training every week, to travel to matches every weekend, accompany teams on tours, living out of hotels and so on.

“Very quickly you could fall back into the same lifestyle.

“Those days are over. Rugby ruled my life for a very long period of time but Rugby isn’t everything guys, it’s just part of life. There are many other things I want to do and experience. Rugby will not define me as a person.

“In my opinion there are too many rugby players at the moment that if you take rugby out of them, have no identity or life. As one of the old brigade that really worries me. We must always take care to cherish and nurture the individual as well.”

Botha’s wise words – delivered with a friendly smile and Buddha like serenity – come in the form of well-intentioned, almost paternal, advice from an old

warrior who has lived his entire career at the sharp end of the sport and, for the most part had a ball, especially his three and bit seasons with Toulon.

He was no angel, far from it, and took no prisoners along the way. More than once he overstepped the line of what is acceptable with bans for butting, punching and inappropriate contact with an opponent’s eyes but he ‘copped’ plenty of bad stuff himself without whinging.

You could also argue that ‘enforcers’ like Botha in the long run stop more fights and flare-ups than ever they start by the deterrent of their mere presence.

He has also had his vocal supporters among opponents and “victims” not least Lions prop Adam Jones who suffered a dislocated shoulder in the second Test in Pretoria when Botha cleared him out at a ruck.

Botha was banned for a month – but the Welshman defended his opponent stoutly.

“Botha shouldn’t have been banned for it, nowhere near it,” said Jones at the time. “I don’t have any complaints. He just cleared me out of the ruck and I got caught. Everyone counter-rucks nowadays and, if anything, I was in the wrong place.

“He just hit me and I was unlucky. So I was surprised to see he got banned. I know we didn’t cite him so I don’t know why the independent commissioner did. It was just a fair ruck from a hard player.”

Despite the bans and a certain infamy Botha has became something of a cult hero with his down-

to-earth approach and obvious uncomplaining enjoyment of the rough and tumble, winning fans and admirers around the world.

There has always been a very real connection between Botha and ordinary club player sitting in the bar on a Saturday night nursing his wounds and swapping tales from the battlefront with colleagues and opponents.

Not moving to France sooner is the biggest – in fact only – regret of his career and that disappointment has nothing to do with money per se because as a World Cup winner and Blue Bulls legend he wasn’t exactly a pauper down in South Africa. In the Top 14 he found both the challenge and style of rugby that brought out the best in him.

Not moving to France sooner is the biggest – in fact only – regret of his career and that disappointment has nothing to do with money per se because as a World Cup winner and Blue Bulls legend he wasn’t exactly a pauper down in South Africa. In the Top 14 he found both the challenge and style of rugby that brought out the best in him.

“The physicality and the pace of the game in the Top 14 fitted me like a glove. It’s much slower than in South Africa and in Super Rugby and, let’s face it, I’ve never been known for my pace. In France I could consistently get to where I needed to be to make an impact on the game.

“There is a huge myth about the kind of weather, ground conditions and rugby you get in France and the Top 14. You actually get a lot of cold, wet weather with muddy tracks and harsh conditions. You’ve got Clermont, Oyonnax, Brive and Grenoble in the hills and mountains and then the coast where it can get very wet and windy – Biarritz that was, Bayonne, La Rochelle, Bordeaux.

“For maybe 30 per cent of the season – at the start and then from the middle of April onwards – the weather is great and there can be a quicker style of rugby but for the rest of the time it’s really hard going, quite heavy tracks, and that suited me perfectly. The rugby is tough – brutal often – and the forwards tend to be older and heavier than anywhere else.

“At 32 when I arrived I felt on the youthful side again and there were guys in opposition packs weighing in at 135kg. So I felt younger and lighter than for a long time!

“That sort of athlete can’t survive long in Super Rugby but in the Top 14 has a role to play. The refs are pretty relaxed as well and for nearly four years I absolutely loved it and cherish the memories from my time in France.

“There is another misconception that the Top 14 is all about old timers moving to France to ‘cash in’. The pay down there is good but what you have also got to consider is that experienced, durable, consistent players – especially up front but not always so – are exactly the kind of individuals who thrive in the Top 14. They are the players most clubs want to sign. It’s a sort of chicken and egg situation.

“France and Toulon were a real proving ground for me. I arrived in quite difficult circumstances. I had gone to the 2011 World Cup with an Achilles niggle and it had flared up badly and forced me to go home early. By the time I got to Toulon I still needed two months rehab and the club weren’t happy.

“Then there was all the talk about us ‘big-name’ internationals – mercenaries – arriving to collect pension cheques and, remember, at this time we had not won a Top 14 final or European Cup. The big signings at Toulon were expected to deliver.

“Former World Cup winner or not my reputation counted for nothing, I started again from nothing and that was the best thing that ever happened to me. I needed to prove myself once more and I became very fit again and hungry for success.

“First I had to earn my place in the team against other good locks and then I had to start delivering week-in week-out. There were good chunks of time in Toulon where I played possibly the best rugby of my career.

“The other big factor for me in France was I arrived thinking that my Springboks career was over. I had effectively said my goodbyes in New Zealand when I made a little speech to the guys about the honour of wearing the jersey just before I flew home to start getting my Achilles sorted.

“After that I was heading for France and at the time there was no understanding that you could play overseas and still represent South Africa.

“Once I had settled and began to play well I started to wonder if that really was it with South Africa. At the very least I would like to have quit Test rugby on my terms, not just see my international career suddenly cut short. As a religious man I prayed to God and asked him, please just give me one more Test in the green and gold and unbelievably he gave me nine more Tests.

“The day the phone rang and it was Heyneke Meyer asking me if I was ready to play for South Africa again was one of the best of my life.

“So I got to play nine more times for my country and who am I to ask for more, that’s why I had complete inner peace when I decided to stand down last November after the game against England at Twickenham. I might well have got through to this year’s World Cup although South Africa have some great young locks on the scene now but that’s not the point.

“I had asked that I be in control of when I end my career and been granted that privilege. So I retired with a smile, on a high, and knowing deep down that I was still good enough to play for the team. That is the perfect scenario.

“I’m happy with my decision and for the first time since I was young I can just enjoy a World Cup as a fan. I will be just coming over here with some friends to support South Africa. I had a little taste of that recently when I went to Ellis Park to watch the Boks against the All Blacks purely as a fan. I couldn’t believe what a great occasion it was, the passion in the stands and all the fun of the build-up and then the post-match stuff. As a player you very much get to live inside a bubble being the professional athlete and sometimes you just forget what a great day out it is and what a great time people are having.”

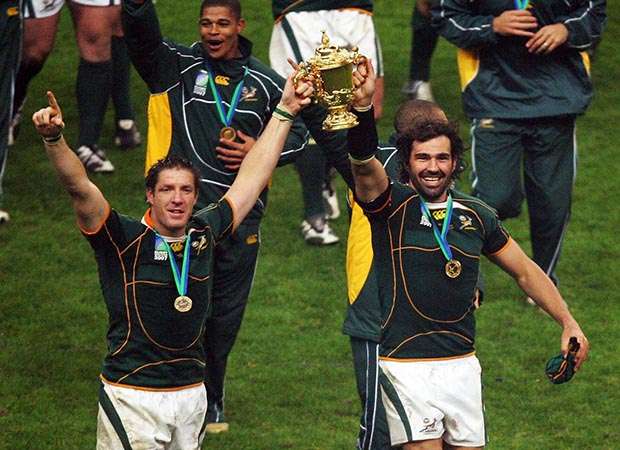

Botha achieved everything in the game domestically and internationally, in fact, a case could be made out for him being the most successful player in history. Three Super Rugby titles, three European Cups, three Currie Cups, a Top 14 Championship, two Tri-Nations titles, a Lions series win (2009) and a World Cup (2007).

But it hasn’t always been plain sailing. Far from it. The World Cup for example has seen just as much heartache as joy. Ever-present during their successful 2007 campaign he has also known the bitter taste of failure in 2003 and 2011.

“We got it all badly wrong in 2003 and it wasn’t a happy time, from Kamp Staalgraad all the way through to our quarter-final defeat against New Zealand. Our entire World Cup campaign in Australia was so centred on beat-

ing England in the pool game that when that didn’t happen, when we got well beaten in Perth, the balloon just burst. We had nothing left really for New Zealand in Melbourne and lost badly there.

“Luckily I was young and still ambitious and used the disappointment as a motivation and was a much wiser and better player by 2007. Those of us who went on from 2003 all learned a lot from 2003 and it put us in good stead.

“But 2007 was an amazing journey with Jake White and the other guys. We clicked just like England clicked in 2003. That is what I believe makes a World Cup winning team. So many senior players hitting their peak collectively, so many leaders in every area. Everybody knew their job and did it and there was great unity within the squad.

“But then in 2011 it went wrong for me with my Achilles injury. Every sportsman knows how difficult and frustrating that can be. I didn’t think we were far away in 2011. We lost a quarter-final against Australia that we should probably have won so we don’t know what might have happened, but there were no teams to fear at that World Cup.

“This year is quite open. France seem to have turned a corner and if Saint-Andre can bring in consistency of selection they will challenge hard. I know talking to the players that is what they crave most.

“England will mount a good campaign but if I use my heart and my head I find it difficult to look beyond New Zealand and South Africa. They could meet in the semi-final which will make it even more interesting.”

British and Irish Lions

Charlie Elliott: The 17 backs I would select for the British and Irish Lions

You must be logged in to post a comment Login