Everybody is famously allowed 15 minutes of fame, but for Northampton wing Andy Hancock that was abbreviated to 15 seconds. That’s pretty much the time, give or take, that elapsed from when Scotland lost possession deep in the England 22 at Twickenham in the last minute of their 1965 encounter to the moment the Northampton wing touched down nearly 100 yards away.

Everybody is famously allowed 15 minutes of fame, but for Northampton wing Andy Hancock that was abbreviated to 15 seconds. That’s pretty much the time, give or take, that elapsed from when Scotland lost possession deep in the England 22 at Twickenham in the last minute of their 1965 encounter to the moment the Northampton wing touched down nearly 100 yards away.

Hancock’s score was certainly one of the greatest individual tries in Test history and, coming right at the death with England trailing 3-0, it was one of the most dramatic and important although in those far off ‘black and white’ days it earned only a draw, not a win. Today five points would have delivered the victory such a virtuoso moment warranted.

But consider this for a moment. That try for the ages, that miraculous moment of genius was the only try Hancock, now 75, was ever to score for England. Indeed he played in only one more Test.

It was also the only time before or since that he can recall scoring from inside his own half at any level of rugby. To cap it all his try coincided with a rare visit to Twickenham from The Queen, not particularly noted as a rugby fan, who like most of the 70,000 had yawned her way through the previous 79 minutes which was frankly pretty tough going.

Andy Hancock was no Usain Bolt, nor was he really a speedster by rugby standards. He was no Ken Jones, JJ Williams, Gerald Davies or Keith Fielding. He was just a very fit and competent club wing, yet out of nowhere came this wonder try exactly 50 years ago.

What strange stars aligned for that to happen? In short, where the bloody hell did that try come from?

After some really good seasons in the early Sixties, England were enduring a dip by the middle of the decade and selection was all over the place, especially in the backs.

It was hugely unsettling for the team but the one positive from that odd dynamic was that almost anybody lacing their boots at senior level in England sniffed a cap and one or two players became very motivated and hungry. And very fit. Hancock was one of those.

“It was my overall fitness that came to the fore that Twickenham, my endurance as much as my speed,” recalls Hancock now exactly 50 years on. “It was such a sapping surface at Twickenham that day, it was treacle. It was a day for a 400-metre runner not an out-an-out speed merchant.

“I had sensed I was near to an England cap at the start of that season and was training like a maniac, three days a week in addition to club training and matches at Northampton.

“I was really going for it in a big way, it was now or never as far as England was concerned and I was absolutely at the peak of condition. I could not have been in better shape. I was no flyer but I was reasonably quick and one of those rugby players who was a yard quicker again in rugby boots with the ball tucked under my arm “The previous month I had been called into the team late on the Friday to make my debut against France at Twickenham the next day. I was at work and my mother phoned to say I was needed at home straightaway because some chap from Twickenham had been on the phone. I went straight back, mother handed me a packed bag with all my kit and a dinner jacket, or at least the poshest jacket I possessed, and five minutes later I was on my way south by train to meet up with the team at their hotel in Richmond.

“I didn’t have time to be nervous. I don’t remember much about the match other than we won 9-6 and I should probably have scored a try chasing a Micky Weston kick but I misjudged it when I went for the touchdown.

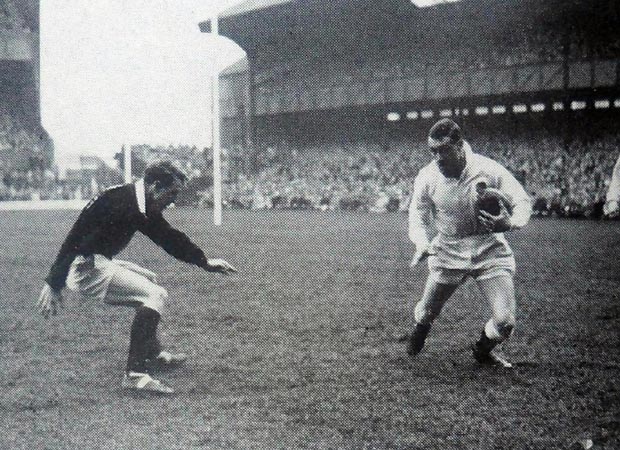

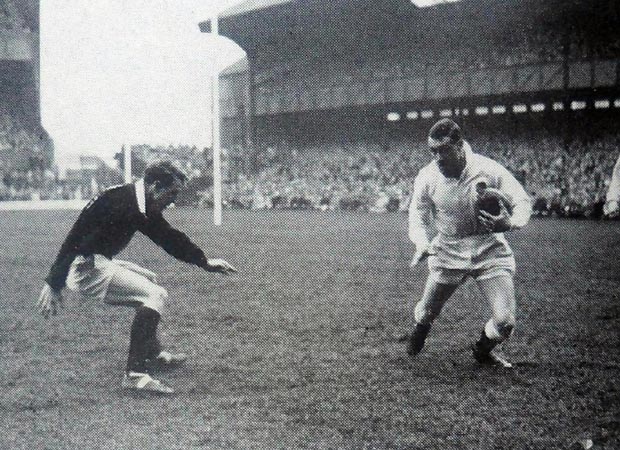

“A month later against Scotland I was the first choice at Twickenham and in many ways I looked on it as my debut proper. It was a well-taken try but a little lucky as well. We, and by that I really mean Micky Weston, caught the Scots out by deciding to run it from so deep after we had turned them over. It was such a dreadful day and pitch, it just wasn’t a day for running rugby. I don’t think it occurred to Scotland for a second that we might try a counter-attack and to be honest it only started out as little experimental foray on our part.

“Ian Laughland was a little unlucky when he slipped as he tried to tackle me for the first time and things started to open up. Budge Rogers was running hard in support and I think he then distracted Stuart Wilson who thought I might be thinking of the inside pass.

“Stuart was a very good player and very quick and on a normal dry day would certainly have taken me to ground but, anyway, he slipped as well and only half tackled me and I was off down the touchline.

“The try-line seemed miles away, it was still more a matter of making as much ground as possible, but I kept going. Ian Laughland was another quick guy – he was a member of that great London Scottish side that used to always win the Middlesex Sevens – and he chased back for a second bite of the cherry right at the end and tackled me around the ankles, but rather to my surprise I was over the line by then.

“It was the strangest thing but my memory is of complete silence through the entire run although I am told the crowd was going mad. It was only a few seconds after I scored the try and I was laying there exhausted that the crowd noise cut in. Throughout the actual try I was in my own world.”

There were those, to a man sitting in the comfort of their stands, who suggested afterwards that, perhaps, Hancock could have run round nearer to the posts to make Don Rutherford’s ‘match winning’ conversion easier. As it happened he pushed it a foot wide. That would be very harsh, though, Hancock was nearly passing out with the effort by the time he was touching down.

Hancock’s is the only score, in terms of its miraculous and unexpected delivery, that compares with Gareth Edwards’ long range effort against Scotland at a muddy Cardiff Arms Park in 1972.

Rather poignantly – as the fortunes of Hancock and England declined – it was repeated every Saturday for the next couple of years in the opening credits of BBC Grandstand, its off the cuff genius mocking England’s plodding endeavours of the time. And then it just disappeared from our consciousness.

“I never scored a try from that distance either before or since. It was a complete one-off and I must admit a source of much pride although I’ve got no reminders in the house except for a team picture of the day, not that I need any reminders.

“You never forget a moment like that. I’ve never seen a still picture of the try ever. I don’t know what happened to the photographers that day, they must have all been down behind the England line expecting another Scotland score I suppose!

“After the game my most urgent thought was that at some stage in my senior career I must score another try like this to prove it wasn’t a fluke.”

Alas that wasn’t to be and the rather harsh truth is that Hancock’s try probably was a fluke in the sense that if enough Test ruby is played over the decades and centuries one or two very great unrepeatable tries will inevitably be scored. Hancock himself, however, could have played 100 Test matches and never come close to such a score again.

Today the scorer of such a try would become an instant celebrity and would be signed up by the biggest club in the land, but back then it barely warranted a pat on the back and by Monday morning it was virtually forgotten. It was also England’s last game of the tournament, they didn’t have another match for ten months when they would open the 1966 Five Nations against Wales. No danger of player burn-out in those days.

What it did mean, though, is that Hancock quickly faded into the background again and by the following season he was in any case beginning to encounter serious injury problems.

“I was held back by injuries during the first half of the following season and then when I finally got back in against France in Paris I suffered a very bad hamstring tear early on,” he said.

“I should have come off but we weren’t allowed replacements in those days and I stayed on the pitch doing untold damage to be honest. Complete madness, really. It took a very long time indeed for the hamstring to heal.

“I had also been asked to make myself available for the 1966 Lions to New Zealand but that went completely out of the window and by the following season I realised I was still nowhere near the fitness I needed and that my England career was over. Three matches. One win, one draw, one defeat, one late call up, one hamstring tear. And one try.

“There was a time when people used to ask me about the try all the time but nowadays I don’t go to matches or rugby gatherings and nobody knows me or remembers the try.

“Playing for England was a wonderful experience and my one regret is that it was such a fleeting part of my career. It was a bit difficult to come to terms with for a while but in the amateur days you just got on with your life and job.

“Happily, when the hamstring finally healed, I enjoyed some of the best rugby days of my entire life as I stepped down a few levels and played with Stafford and would you believe the Chelmsford Undertakers who are the Vets team at Chelmsford rugby club where we had some great fun at Coronation Park.

“I kept going until I was nearly 40 when I managed to rip a tendon off my pelvic bone and it was clearly a message from above to give up. I was on the end of some great team scores for those clubs that in a way gave me just as much pleasure as the try against Scotland but they were witnessed by the proverbial two men and a dog and only those of us concerned knew that they were planned and plotted and what a great deal they meant to us.”

Fifty years on nobody has been in touch from Twickenham – yet anyway – which seems a shame. This England group is keen to draw strength from the past and to honour those who have worn the shirt before them we are told. Personally, I can’t think of a try that better typifies the defiant, never-say-die, backs-to-the-wall attitude that modern day England teams should aspire to.

In the absence of any contemporary photographs the RFU should commission a painting of a determined Hancock setting out on his lone, seemingly doomed sortie with the length of Twickenham stretching before him and make it the last image England view as they troop our of the tunnel which is now festooned with picture of past glories.

2 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment Login

Leave a Reply

Cancel reply

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

English Championship

What the new Championship format could mean for English rugby

Pingback: go to this website

Pingback: niches youtube