England have found the going tough in Cardiff over years both at the Arms Park and the Millennium Stadium. Indeed at one stage between 1963 and 1991 they went 28 years without a win in the Principality their longest barren spell on the road in Championship history.

England have found the going tough in Cardiff over years both at the Arms Park and the Millennium Stadium. Indeed at one stage between 1963 and 1991 they went 28 years without a win in the Principality their longest barren spell on the road in Championship history.

If not quite a graveyard – historically England win one game in three in Wales – it’s been a venue where humble pie has often been eaten and harsh lessons learned. Particularly the latter because it is also true that some of England’s best seasons have come directly after being shredded in Cardiff and being forced to make radical b ut necessary changes.

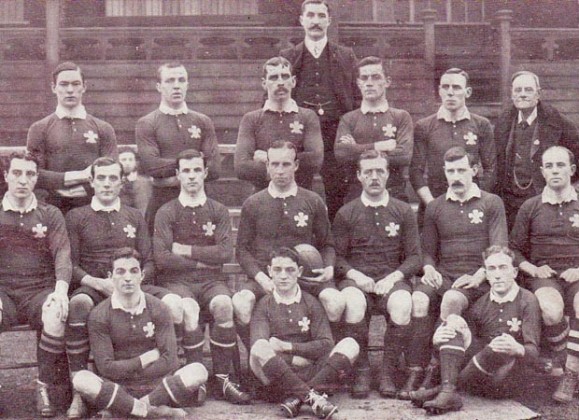

Defeat against Wales was common place early in the 20th century, indeed England went ten years without a win home or away against Wales from 1899 to 1909 but the undoubted low point was a 25-0 walloping in 1905 when they leaked seven tries.

Dick Jones, George Davies and speedster Teddy Morgan were the stand-outs for a rampant Wales and it was scarcely much better two years later when England leaked six tries and lost 22-0. The misery of playing and losing in Cardiff was beginning to seep into the English psyche.

England’s 28-6 pummelling in 1922 was remarkable in that it came slap bang in the middle of a golden age for England rugby. Swings and roundabouts. The previous season England won the Grand Slam and straight after the hammering in Cardiff they won their final three Championship games and then marched to a Grand Slam in 1923. So what went so badly wrong?

Rugby might be a team game but the answer here could be just down to one man – fly-half WJA Davies. The Naval man was – and remains – the great unheralded superstar of England rugby even if he was born in Pembroke and could have been claimed by the Welsh. “Born in Wales but learned and played all my rugby in England,” was his stock reply to all those who asked.

After losing in his debut match against South Africa in 1913 Davies never lost again in an England rugby shirt and was a key member of four Grand Slam winning teams either side of WW1. But for five seasons lost the hostilities he would have collected 40-plus caps not 22.

Davies missed just one game due to injury and that was the debacle against Wales in Cardiff in 1922. Without Davies, who was also their captain, at the helm England were all at sea. With him back in charge they immediately resumed their dominant ways.

Heads rolled after the big defeat. Of course they did. Three players – stand-in captain LG ‘Bruno’ Brown, full-back Barry Cumberlege and Ernest Hammett – Newport-born and a Wales football player and tennis representative – never played for England again. Their summary dismissal caused much regret among Davies, on his return to action, and Wavell Wakefield who was fast becoming one of the leading figures.

As Davies, generous to a fault, wrote in his memoirs: “In my absence the team was captained by LG ‘Bruno’ Brown. No better person could have led the English team and it was an irony of fate, owing to a combination of circumstances that the team played very badly. No finer character than Bruno ever stepped on or off a rugby field.”

Wakefield, meanwhile, was annoyed at the axing of Cumberlege who later became one of the game’s top international referees: “There were many changes after the Welsh fiasco …personally I think it was a great mistake that Cumberlege was dropped for he had much football left in him and did better than anybody else would have done in the most adverse circumstances. I saw him ten days after the match and the whole of one side of his body was still black and blue.”

Fast forward to Wales’ 34-21 win in 1967 and England’s despair was all about Wales’ 18-year-old debutant full-back Keith Jarrett who scored 19 points and a wonder try down the left touchline that still gets replayed regularly.

I use the term ‘full-back’ advisedly, though, it was just about the only time he ever played there.

Jarrett was not your run-of-the-mill rugby player. The son of Glamorgan cricketer and Newport RFC groundsman Howard Jarrett, his grandfather, of Polish descent, was a classical pianist who changed the family surname from Jarewski. A prodigiously talented schoolboy centre and occasional wing at Monmouth he played, under age, for Arbertillery under an alias – Keith Jones – and was smuggled out of the ground after games to avoid a questioning Press. He also played first-class cricket for Glamorgan against India and Pakistan.

He officially left Monmouth at the end of the 1966 but kept playing for their Sevens team – hence his appearance at the Rosslyn Park Sevens – and was called into the Wales squad when another youthful prodigy at full-back Terry Price endured a tough afternoon of missed goalkicks against France. The Big Five cast their eyes around and their gaze fell upon Jarrett.

At the selectors request Jarrett famously had a run-out at full-back for Newport against Newbridge the week before the England game and was so poor his captain David Watkins switched him to centre at half-time to preserve what was left of his confidence.

Come the day, though, and he was to the manner born, nervelessly slotting two penalties and five conversions and racing away for one of the most memorable debut tries on record, an absolute belter when the game was delicately poised at 19-15 midway through the second half. Wales piled on the points after that although England did hit back at the end, Coventry lock John Barton covering himself in glory with two tries.

Jarrett said: “I had to deal with a ball like this once before and fancied it would bounce ‘big’ and stand straight up which is exactly what happened. Because of that anticipation – luck – call it what you will it meant that I took the ball absolutely flat out which gives you a big advantage as an attacker. Keith Savage, the England wing, was the only England player anywhere near but such was my speed and the angle I had on him that I was able to brush him off. The biggest problem was actually staying in play because I was very close to the touchline but I just managed to keep my balance.

“The match and the try was big news but then again it was the last international of the season and I didn’t have to play two weeks later when I might not have played so well. The fuss seemed to last all summer until the next season.”

Jarrett was a sportsman sprinkled with stardust and his was a fairytale start at the top level but his story had no fairytale ending. Two years later, and after a brief Wales career of ten caps, he turned professional with Barrow and did well, but at the age of just 25 and on the eve of joining Wigan he suffered a stroke and was never able to play again.

Two years later England were on the receiving end again, this time going down 30-9 with wing Maurice Richards taking advantage of Barry John’s genius inside him to collect four tries. Richards was another who headed ‘North’ soon after his finest moment for Wales, signing for Salford where he scored over 200 tries in a long career.

Budge Rogers captained England that day in Cardiff and ruefully recalls the occasion: “It was a strange game in many ways, not least because we had played rather well in the first half and were a bit unlucky that the score was only 3-3 at the break. But then they hit a fantastic purple patch and we got absolutely hammered.

“That was a real taste of what was to come in the Seventies. In the backrow that day myself and fellow flanker Bob Taylor were asked to play left and right which I never liked and I found myself out of position or a couple of yards away from where I needed to be most of the time.

“The consequences of that game were huge, both personally and for England rugby. Unsurprisingly I lost my place in the team and in fact it was my last ever capped game for England which was a hard pill to swallow at the age of just 30 and at a time when generally I’d been playing well.

“The bigger picture changed dramatically as well. As a direct result of that defeat in Cardiff the RFU bit the bullet and started modernising. Don White was appointed as England’s first-ever coach and a 30-man England squad announced early in the autumn so that they could train together every other Sunday morning at various grounds in the Midlands.

“The result of all that was a first victory over South Africa in the December. I had tried to institute extra training in the squad 3-4 years earlier but got headed off by the Bob Weighill the RFU secretary. In the end it all came a bit too late for me, alas.”

Big away defeats in Cardiff often seem to have been seminal moments in England’s rugby history. A depressing 27-3 reverse in 1979 just about summed up a decade of underachievement made all the more frustrating by superb Test victories on the road against South Africa and New Zealand.

The paucity of that performance at the Arms Park in 1979 finally galvanised England into action just as it had ten years earlier. Time was running out for the likes of Tony Neary, Roger Uttley, Fran Cotton, Steve Smith, John Horton and Mike Slemen and it was high time, under the uniting captaincy of Bill Beaumont, to achieve something tangible in an England shirt. A year later England were celebrating their first Grand Slam in 23 years.

Two years ago was one of the strangest, as well as biggest defeats England have ever suffered in Cardiff. Stuart Lancaster’s team arrived looking to close out a Grand Slam to add to their victory over New Zealand in the autumn. This was a strong, fit, well-motivated England team and a generation of players ready to write the chapter in the history books. Yet they were unceremoniously dumped on their backsides. How come?

No mystery really, it was an old story as chronicled above. Wales confronted with the white shirts of England on their home patch, raised their game five percent while at the same time England froze and were some way off their best. Leigh Halfpenny kicked his goals, Alex Cuthbert ripped in for two tries and the rest was hysteria.

1 Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment Login

Leave a Reply

Cancel reply

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Latest News

Charlie Elliott: Ben Youngs’ Best Career Moments

Pingback: buy white cherry runtz kush