PETER JACKSON tells the colourful story of one of the greatest coaches of the amateur era, the inimitable Ray Prosser who died last weekend at the age of 93.

Monday, January 20, 1975 – training night at Pontypool RFC in readiness for the next match: home to Glamorgan Wanderers on Saturday.

Graham Price rolls up along with everyone else, unmoved at the praise showering over him since the climactic end to his Test debut in Paris a little more than 48 hours earlier. If there is an extra spring in his step it is because the coach whose opinion be values more than any other will surely let him have the benefit of his opinion on the opening round of the Five Nations.

Ray Prosser barks the orders and the players go through the usual punishing Monday night routine. Still no word from Pontypool’s demanding coach, no acknowledgement as yet of what the whole of Wales has been talking about all weekend, the sight of a tighthead prop galloping almost the length of the field in the last minute of an international and scoring in the corner.

The players know nobody knows the game quite like ‘Pross’. And nobody knows that better than the hooker who had been on the Lions tour the previous year, Bobby Windsor, and the flanker who would run the Lions pack on the next tour in two years time, Terry Cobner.

Prosser, Pontypool born and bred, had been a Test Lion when both were in short trousers. Meanwhile, another local boy, one who would play a staggering twelve consecutive Tests for the Lions over three tours, waits to say what his mentor thinks of his performance in Paris.

A Wales team containing six new caps floated home the previous day after beating France by the length of the Champs Elysees, 25-10. The rugby world is agog at the result and, in particular, the sight of one of the Test novices, Price, covering some 70 metres at the Parc des Princes to score the last try.

Prosser ends the session, decreeing that it’s ‘time for a cup of tea and a bite to eat.’ Walking off Pontypool Park, he approaches the club’s newest international. At last, the big moment has arrived.

“Pricey,” he says. “That prop you played against on Saturday wasn’t up to much.”

“What makes you think that?”

“Because if he’d been any ******* good, you wouldn’t have been able to run that far at the end of the game.”

Privately, Prosser was thrilled but, like many of his generation born during The Roaring Twenties, he never allowed himself to indulge in extravagance of any kind. His way of ensuring Price’s feet remained on tierra firma was not unlike Sir Alf Ramsey’s retort to Geoff Hurst the day after England won the FIFA World Cup in 1966.

After the debrief, Hurst, still the only footballer to score a hat-trick in a World Cup final, headed for home with a parting shot which sounded to the manager more like a statement than a question: ‘See you for the next match, Alf.’

To which Ramsey is said to have responded with the straightest of faces: “If selected, Geoffrey. If selected.”

Unlike Sir Alf, Prosser never had elocution lessons. Like Ramsey, he had an aversion to the limelight. The bigger the win, an almost weekly event during the mid-Eighties when ‘Pooler’ beat just about everyone bar the Grand Slam Wallabies, the harder it became to find Prosser anywhere near the celebrations.

He would walk through the park from the rugby ground to the clubhouse and make himself scarce, all the more rapidly if there was any glory on offer. He would disappear into a quiet corner downstairs with old friends, preferring to buy his own beer rather than help himself to the free stuff on tap for the players.

Bobby Windsor, in the mid-Seventies arguably the best hooker in the game and certainly the most ruthless, recalls that time. “As players we went upstairs for our grub and free beer,” he said in his acclaimed book The Iron Duke.” ‘Pross’ never did. He always stayed downstairs. Many’s the time we begged him to come upstairs and have a drink with us.

“He’d always find an excuse not to and I can see now that he was being clever, that he felt he couldn’t get too close to the players, that his bollockings would carry more weight if he stood back a bit and kept his distance.”

Ray Prosser, who built the renowned assembly line of hard-nosed forwards known the world over as the Viet-Gwent, has died in his 94th year.Flags at every rugby club in Wales ought to be lowered to half-mast in honour of his colossal stature.Deepest sympathy to family and friends. https://t.co/YdSVCVSvTX

— Peter Jackson (@JackoRugby) November 22, 2020

Like Ramsey, Prosser took an unfashionable club from rock bottom to unscaled peaks of winning consistency. He would have loved the fact that they managed the difficult trick of being almost as unfashionable at the top as they had been at the bottom.

He drove a bulldozer for a living and the early struggles following his return as head coach by popular demand in 1969 left him feeling that the bulldozer got some of its own back most Saturdays. In season 1970-71, Pontypool lost 32 of their 45 matches.

For three seasons in the mid-1980’s, Prosser’s Pontypool played 136 matches, winning 120, almost 90 per cent. Anyone looking down his nose at the results and sneering about ten-man rugby would be reacquainted with the facts: a hat-trick of Welsh titles and tries by the hundreds. In four seasons, David Bishop, Chris Huish, Goff Davies and Bleddyn Taylor ran in more than 300 between them.

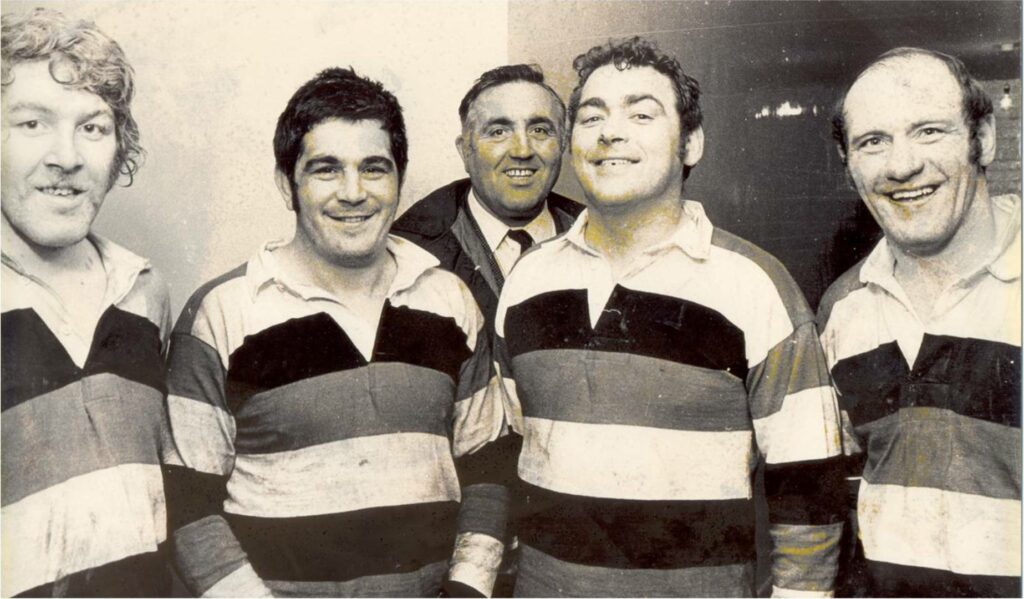

By then Prosser had given Wales and the Lions the Pontypool Front Row (Price, Bobby Windsor, Charlie Faulkner) and forged a father-son relationship with the ultimate symbol of the ‘Viet-Gwent’ – Terry Cobner.

His description of the triple champions as ‘just a good, wormanlike side’ fitted perfectly into Prosser’s no-frills mentality. His philosophy, that all rugby matches are won and lost up front, never changed.

Wales capped him in 1956. Three years later, with the Lions in New Zealand, his worthy reputation for being as tough as old boots underwent a brutal examination while local referees turned their blind eyes.

According to Windsor, Prosser would ‘joke about going into the scrum in that last Test arse first, so they could kick him there for a change instead of in the mouth.”

Not surprisingly, Prosser never had any room for softies. “He knew more about the technicalities of forward play than anyone I ever met: the positions of your feet, positions of your body, when to bind, when not to bind,” Windsor said.

“He’d always give you a few options so that if the opposition did this, then you did that. If it didn’t work, then you switched to Plan B or Plan C and one of them would always work. You were never stuck.”

In building one of the great club teams of the amateur era, Prosser did so by refusing to break the habit of a lifetime. Anyone asking for money got short shrift, as Windsor discovered before leaving Cross Keys for Pontypool.

When Windsor inquired as to how much he would be paid, Prosser gave him a dirty look and a response to match: “We pay f*** all. If you’re really lucky, we’ll give you a game and that’s all we’ll be giving you.”

The way Prosser saw it, playing for Pontypool was something money could not buy. And Windsor was streetwise enough to recognise the priceless value of working with a coach who would turn a good player into a great one.

PETER JACKSON

Latest News

Super Rugby Americas: Round Ten Review

British and Irish Lions

British and Irish Lions: Biggest winners and losers from Andy Farrell’s selection

You must be logged in to post a comment Login