Of all the international rugby players in all the world, one still stands out from the rest more than 20 years after his death – Bill Shankland of Warrington RLFC.

There are several reasons why, even in the most revered company, he remains a man apart. Who else was a good enough swimmer to compete against multiple Olympic gold medallist Johnny ‘Tarzan’ Weissmuller; good enough to have been in the same cricket team as Don Bradman and a middleweight boxer able in his Eighties to flatten a pair of would-be muggers in downtown Poole?

His sons tell how, as a life-saver on Bondi beach, their father rescued several swimmers from sharks in scenes that might have inspired Jaws! by punching the great whites on the nose.

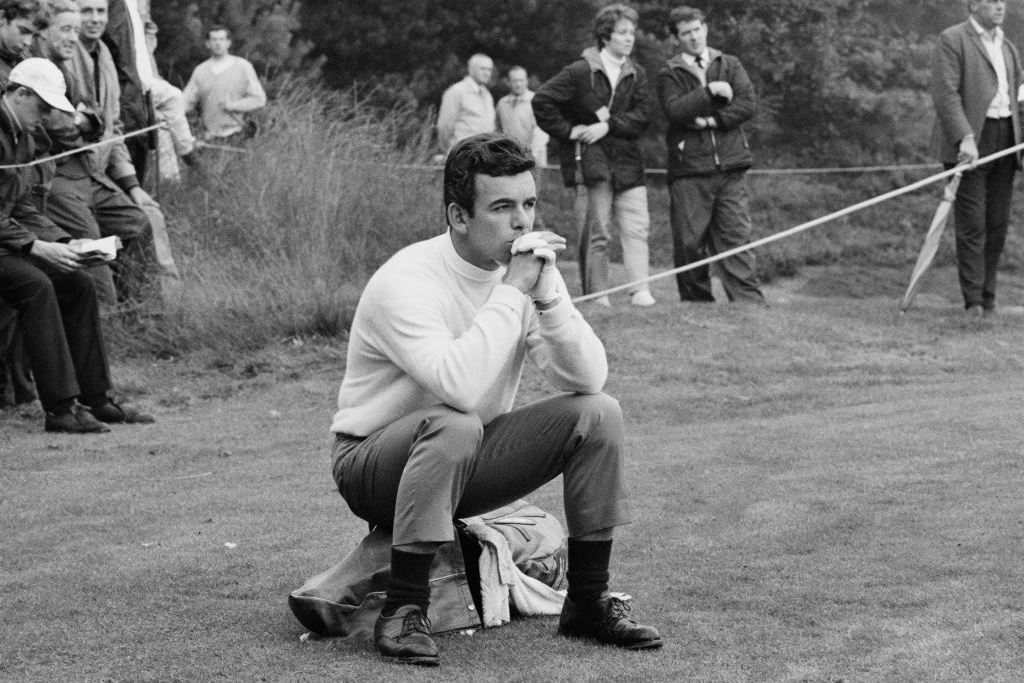

Compared to that, Shankland’s transformation from a budding Wallaby fly-half into a League Test centre with the Kangaroos sounds almost mundane. His greatest claim to fame as the all-rounder to beat them all had nothing to do with swimming, cricket, boxing, life-saving or rugby, but as a golfer.

Even at the height of his rugby career, Shankland’s ability to bring the most intimidating golf courses to their knees had been noted in the highest circles of high society. Lining up with Warrington for the 1933 Challenge Cup final against Huddersfield, the first at Wembley, the Prince of Wales stopped when Shankland was presented to him.

“How’s your golf?” the future King Edward VIII of abdication notoriety asked.

“Fine, sir,” said Shankland. “How’s yours?”

Shankland’s was so fine that he finished third in the last Open championship before the Second World War and tied fourth in the first one after it eight years later, at Hoylake where he led the tournament with three holes left only to land in a pot bunker at the par-five 16th.

Getting out did enough damage to prevent Shankland becoming the first Aussie Open champion, before Peter Thomson and Kel Nagle and long before anyone had heard of Greg Norman, The Great White Shark. Maybe that was just as well given Shankland’s track record for dealing with the species.

His bunker trouble allowed Fred Daly to take the Claret Jug to Northern Ireland for the first time. Shankland gave the Open another serious go four years later at Royal Portrush, finishing tied sixth behind the champion, Max Faulkner.

“Bill was a big, tough bloke who played Rugby League for Warrington,” Faulkner said years later. “My wife Joan and I never forgot the fact that he was the only pro who wrote a letter of sympathy to us when our daughter, Hilary, contracted polio.”

Shankland had given seven of his best years to Warrington and lost six more to the world war. He competed at his last Open in 1956 at the age of 39 and if he had run out of time as a player, he had plenty left to do the next best thing and teach a ‘cocky’ English teenager how to win it.

As the professional at Potters Bar Golf Club, Shankland took on an assistant at £6-a-week, ‘a cheeky devil’ from Scunthorpe. The US Open at Winged Foot next month marks the 50th anniversary of Tony Jacklin’s success at Hazeltine the year after he won the Open at Royal Lytham.

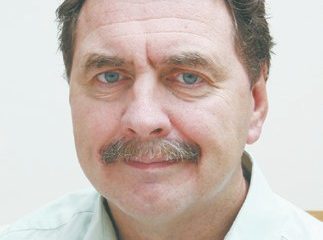

“I watched him hit that final drive dead straight down the 18th,” says Bill junior, at 87 the eldest of Shankland’s three sons and once a three-handicap county golfer. “Tony’s swing had Dad written all over it. I know Dad transformed his swing and made it much more compact because I watched him do it.

“He had a strong work ethic, father did. His attitude was: ‘Stop whingeing and get on with it.’ If it hadn’t been for the war, I reckon he would have won the Open. Tony never seemed to give Dad much credit.”

There wasn’t much love lost between teacher and pupil. “There were times when life was heart-breaking,” Jacklin has said of his early years. “Long hours with ‘Shanko’ seldom satisfied with what I was doing.”

While Jacklin likened it to ‘doing my National Service but I wouldn’t like to go through it again’, he has conceded that he couldn’t have had ‘a better grounding’ and that Shankland imbued him with a winning mentality.

“Dad was without doubt one of the greatest golf teachers of his time,” says his middle son, Florida-based Craig, truly a chip off the old block given his induction to the US Golf Hall of Fame in New York as a teaching pro.

As well as being a professional in his own right, youngest son Dale also wrote the autobiographies of Johnny Miller and Judy Rankin. For all their success States-side, nowhere is the name Shankland more revered than at Warrington.

He died there in September 1998 from a heart attack the day after his last appearance at Wilderspool at the age of 91, leading the cavalcade of old players to mark the club’s centenary.

“We went out to the middle of the pitch and the crowd went wild,” says Bill, junior. “I held his hand up and he gave them a wave.”

In his pomp, one of Shankland’s tricks had been to place the caps from beer bottles between his fingers and squeeze them until they bent. “I was lucky with my sport,” the old man once said. “I could do anything. I was an athletic chap.”

He could say that again…

British and Irish Lions

Henry Pollock’s rise to stardom continues with 2025 British and Irish Lions selection

British and Irish Lions

Maro Itoje named British and Irish Lions captain for tour of Australia

You must be logged in to post a comment Login