October 4 is the 100th anniversary of the death of Dave Gallaher, killed in action on the first morning of the Battle of Passchendaele.

October 4 is the 100th anniversary of the death of Dave Gallaher, killed in action on the first morning of the Battle of Passchendaele.

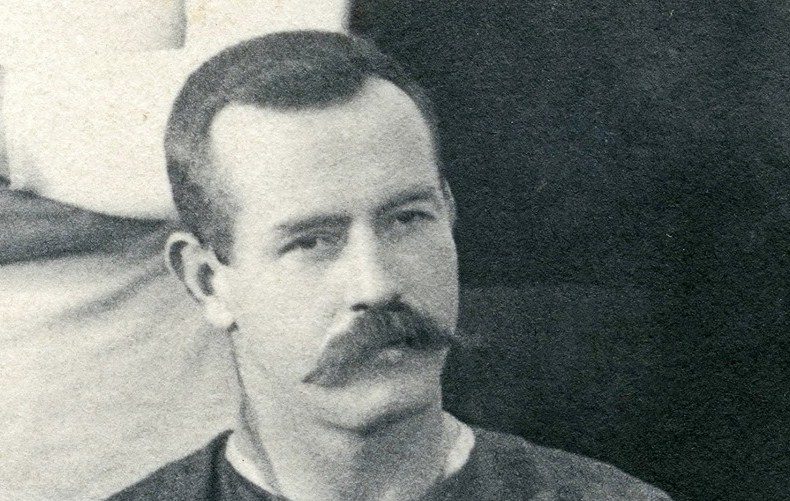

Brendan Gallagher assesses the Irish-born soldier and rugby player widely recognised as the founding father of the All Blacks and explains why his influence is still felt so strongly today.

Dave Gallaher so obviously forged the All Blacks template that trying to divine what made the man tick is time well spent. As well as being an outstanding and innovative rugby player Gallaher was an uncompromising ‘hard case’ of military bearing who wouldn’t put up with any nonsense as he demonstrated on the long boat journey from Auckland to Plymouth. Indeed, I rather suspect that trip half way round the world was the making of the 1905 New Zealand tour party and therefore the All Blacks. We need to investigate further.

The tour to Britain was a massively ambitious, expensive, prestigious and exciting project but initially there was mutiny afoot within the squad. In the ‘final trial’ for selection the North Island had caused a major shock by hammering the fancied South Island 28-0 which caused a hurried rethink and late influx of North Island players into the tour squad. That included Gallaher who hadn’t been among those originally sounded out for the eight-month tour back in January when inquiries about availability had been discreetly made.

There had been suggestions that at 29 – considered old at the time for an amateur sportsmen – Gallaher might be too long in the tooth for the arduous trip ahead. He had also spent two years away from New Zealand fighting in the Boer War and although he had returned in time to win his first cap against Australia and then play in one Test against the 1904 Lions it seemed he might even be poised to announce his retirement. Much later it emerged that Gallaher was in fact already 31 in 1905 having ‘lost’ two years from his age to ensure there were no hold ups when volunteering to serve in South Africa.

The North Island’s win over the South changed everything. Not only was he called up by the tour party he was then announced as captain. Those in the South were immediately up in arms at the number and influence of the North Island contingent, especially the predominance of Aucklanders and it all got very fractious. By way of a compromise, the Union appointed Otago’s Jimmy Duncan – who had retired from playing only 18 months previously – as New Zealand’s coach despite the selectors being adamant they didn’t want a coach and would have much preferred an extra player.

In the event Duncan travelled but was largely side-lined with the coaching very much the domain of Gallaher and his best mate Billy Stead, who possessed one of the sharpest rugby brains in history.

Despite smiles for the Press and well wishers as they left, tensions were running high and there was insurrection afoot on the SS Rimutaka as tour manager George Dixon recorded in his dairy: “Eight days into the voyage a crisis arose when Gallaher announced at a team meeting that he was resigning the team captaincy immediately. Stead also declared that he was standing down as vice captain. Gallaher, speaking to the assembly, said that it had become apparent following the team’s departure from Auckland that the players wished to appoint their own captain.

“I intervened, advising the gathering that the appointment made by the New Zealand Rugby Union had to stand, that they could not be varied at the whim of a group of players. I felt that the position was awkward. Frank Glasgow, after weighing the comments from all sides, put forward a motion that “this meeting heartily endorses the appointments made by the New Zealand management committee. I decided to accept the motion which, mercifully for the good of demanding tour was carried with 17 of the 29 persons present supporting it.”

Glasgow, it should be added, was a well-respected flanker who had played for both the North Island and the South and represented Wellington and Southland.

Gallaher had called the malcontents’ bluff, a classic pre-emptive strike. And then, having had his captaincy reconfirmed by the democratic process he cracked the whip like never before. Did he ever. And of course he knew from his Army days that when you are going into ‘enemy’ territory idle hands make devil’s work. From now on he would be on their case 24-7.

In those early days of touring most teams – cricket and rugby – went to seed on the long sea voyage through over indulgence and lack of exercise. Gallaher was having none of it. This was no bloody jolly, as had appeared the case on early Lions tours to the Antipodes. New Zealand were on a mission.

Every day on board would start with a workout at 7.45am followed by a short break for breakfast before running, sprinting and agility training on deck from 8.45 to 10am. Then came scrummaging practice for the forwards, skills for the backs, and there would be another similar session at 3pm every other day. Most afternoons were spent in the ship’s well-appointed gym where boxing was the main occupation along with Sandow developers – a collection of barbells pioneered by the renowned German bodybuilder Eugene Sandow.

The New Zealand captain also organised a shift pattern for all his team, four at a time, to spend two hours down the stoke hole and coal bunkers putting in some hard-manual labour which was hot work in the tropics. By the time they reached Plymouth, New Zealand were in prime shape. An early example of train hard, play easy.

At team meetings in the saloon bar every night he rammed home the message – how could a small nation like New Zealand hope to compete against the motherland if they were bickering and fighting among themselves? Hard training, discipline, efficiency, courage and teamwork – Gallaher demanded everything from his men that he had already displayed himself in the guerrilla warfare exchanges on the High Veldt. The New Zealand modus operandi was in place and has never changed.

Gallaher employed science and strategy as well. Along with Stead and Billy Wallace, another trusted lieutenant, they put into place what we would readily recognise these days as a gameplan. Hookers were to throw the ball in at the line-out which was an innovation and the forwards arriving for a scrum would take up predetermined positions rather than the ‘first up first down’ method that were the norm.

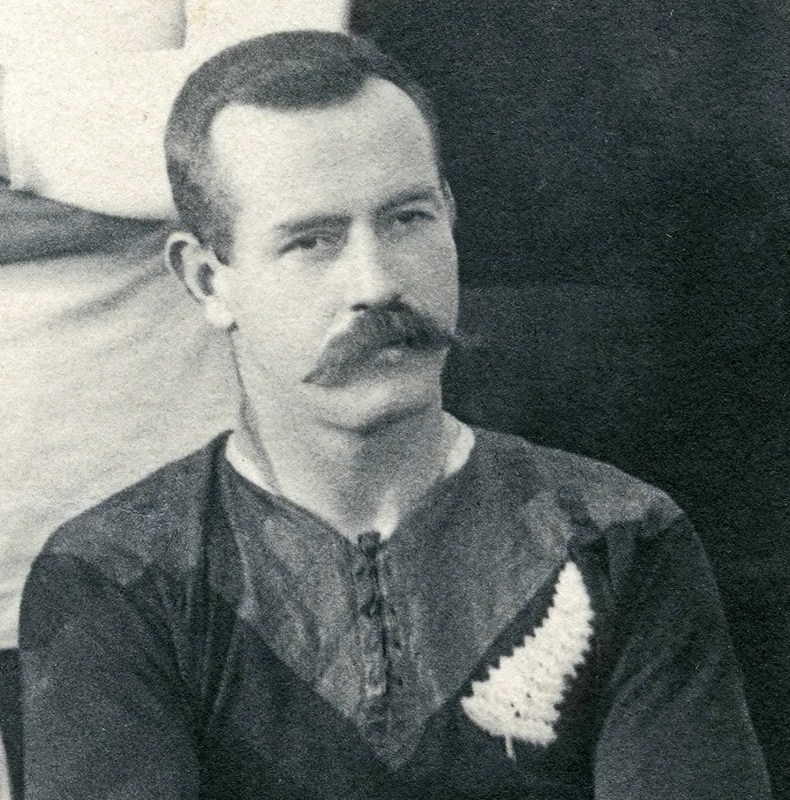

There were to be well drilled set-piece plays and calls in the backs, the use of dummy passes was extensive and most radical of all, Gallaher himself redefined the art of back row play by standing off and breaking from the scrum and getting among the opposition scrimmage to prevent release. The British Press christened him the ‘Rover’ – rugby’s first sighting of the modern-day flanker.

New Zealand started with a clatter, a whopping 55-4 win at the Exeter County ground against Devon who were a power in the land and who were to easily win the County Championship later that season. The local Exeter Express and Echo immediately dubbed New Zealand the All Blacks on account of their striking all-black kit which alas rather discounts the more romantic notion put forward by Wallace when he wrote home. Wallace claimed the nickname came from a report later in the tour in a London paper that insisted New Zealand played as if they were all backs and a sub had changed it to All Blacks

The Devon match was the start of a triumphant march through Britain and Ireland – not to mention a hastily arranged Test in France and two exhibition matches against British Columbia in San Francisco – which saw the All Blacks win 34 of their 35 games on tour with just the solitary narrow loss, in controversial circumstances, against Wales in Cardiff. In total they scored 976 points and conceded just 59.

Gallaher played in 26 of those games and missed just one of the five Tests, being injured for the game against Ireland in Dublin. Although his team were much praised and feted for their sensational brand of rugby, his abrasive style and controversial Rover role, ensured that Gallaher himself received a good deal of criticism.

Perhaps he just became the target for a disgruntled British Press struggling to cope with New Zealand’s superiority but it was water off a duck’s back. Gallaher was the first in a long line of All Blacks skippers who couldn’t be goaded or distracted from the task in hand. The fact that he was taciturn in the extreme at Press conferences probably also irritated the media.

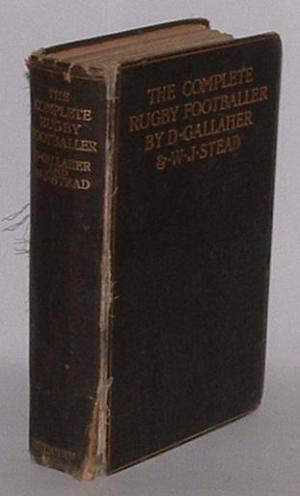

As the tour wound up, Gallaher and Stead used the voyage home to write The Complete Rugby Footballer, a 300-page master class in rugby. As the Auckland Star put it: “Eventually Gallaher’s greatness as a player and captain became so generally recognised that one of the big paper proprietaries approached him to write a book on the rugby game. Sufficient inducement was offered to overcome his reluctance to attack this unwanted enterprise, and he and the vice-captain J W Stead collaborated in a work which was printed and is the most exhaustive and finest written exposition of the rugby game that has yet been printed.”

On returning to a rapturous welcome, Gallaher retired and in no time at all married Nellie Francis, sister of his fellow All Black Arthur ‘Bolla’ Francis. He soon became an Auckland selector and quasi coach and served as an All Blacks selector and father figure from 1907-14 during which time they played 50 matches, won 44, drew two and lost just four. He also joined the ancient order of Druids, a small little know masonic type organisation with branches around the world. A young Winston Churchill was probably its best-known member.

Gallaher’s place in New Zealand rugby’s pantheon was already assured before World War 1 broke out but the circumstances of his death only added to his reputation. Too old to enlist, he reluctantly accepted, to start with, that he would have to sit this one out but his attitude hardened when a younger brother Douglas was killed in action at Laventie on June 3, 1916. A third brother Henry was to die on the Western Front in April 1918. Two other brothers Charles and Laurence survived hostilities.

News off Douglas’ death changed everything and Gallaher, a man of some influence, pulled whatever strings needed pulling and again set sail in the SS Rumitaka, but this time he was headed for Britain and a training camp on Salisbury Plain before deployment on the Western Front.

First he fought at Ypres, the notorious battlefield where so many perished, and after being briefly relieved after that bloodbath his men began intensive training for the Passchendaele offensive and on Oct 3, 1917, they returned to the front where the battle station was a series of massive shell holes.

At 0600 hours on Thursday October 4, 1917 Sgt Dave Gallaher of the Second Auckland Regiment gave his men one last pep talk before leading them over the top for the last time. Within seconds a piece of shrapnel smashed through his helmet as his troop came under fire from a German stronghold named Korek situated on the highest point of Graventafel Ridge. Mortally injured he was carried from the battleground. He is buried at the Nine Elms British cemetery at Poperinge in Belgium.

Even in death his presence had reached out. An Irish priest was giving the last rites to a soldier, Edward Fitzgerald, at the Australian clearing hospital No.3 when he drew the fallen man’s attention to a stricken colleague nearby. “Do you know who that is, on the next table?” the padre asked. Fitzgerald shook his head. “That is Dave Gallagher, captain of the 1905 All Blacks.”

His team-mate and full-back from the 1905 tour, Ernest Booth, wrote shortly after news of Gallaher’s death: “Dave was a man of sterling worth, slow to promise but always sure to fulfil. Girded by great determination and self-control, he was a valuable friend and could be, I think, a remorseless foe. He would reason everything out his own way, even if it took him two pipe fills of tobacco. As an opponent in play he was merciless, wanted everything and all, but I honestly think he never meant to be anything but legitimate and fair.”

Mother Maria taught young Dave meaning of determination

Mother Maria taught young Dave meaning of determination

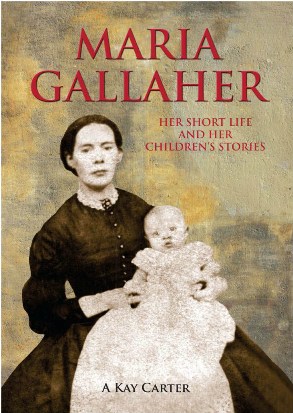

ANYBODY looking for clues as to what made Dave Gallaher the man he was should start with his Irish family and, in particular, his remarkable schoolteacher mother Maria who died of cancer at the age of 42 after bearing 13 children and supporting the family singlehandedly for much of the time after the emigrated to New Zealand.

The Gallahers were from Ramelton in County Donegal in what was then politically part of the UK but is now very much in the Republic of Ireland. They by no means lived in grinding poverty. His father James, who was 32 years older than his wife, was a shopkeeper and his wife Maria McCloskie was a highly thought of teacher.

Together they had already produced nine children, three of whom died in infancy, before they took the tumultuous decision to sign up to a much hyped colonisation programme which involved transporting 4,000 Ulstermen and women to the emerging colony of New Zealand and, in particular, the specially built townships of Katikiti and Te Puke.

It was more the spirit of adventure than anything that took over as they embarked the Lady Joceylyn in Belfast. Their project was the brainchild of Lord George Hill who intended to set up Katikiti as an antipodean depot for the Donegal Knitting company. Hill’s death six months after the Gallaher’s arrival took the steam, not to mention the finance, out of the scheme which, in any case, was over-ambitious and ill timed.

Following Hill’s death the Gallahers were left in a pickle. Their surname incidentally had been noted down incorrectly by immigration officers in New Zealand, the soft second G somehow being dropped, henceforth the family were known as the Gallahers not Gallaghers.

Dave had been nearly five when the family left for New Zealand and life became very tough from the off. Although James fathered another four children his health became very poor and Maria emerged both as the main breadwinner – being the headteacher at No 2 school at KatiKati – and the mother of nine children now.

Not resting from dawn to dusk, she manged this with determination and some style before suddenly being taken ill. Her death was widely mourned among New Zealand’s Irish community and beyond.

Strangely there is no record of Dave Gallaher visiting kinsfolk in Donegal – not even a younger brother James who as a six-week old infant had been left with relatives in Ramelton when the family emigrated – when the 1905 All Blacks spent a week in Ireland.

That doesn’t mean to say there wasn’t an unrecorded reunion as some stage – Gallaher was not as you may have gathered the type for making a fuss about personal ‘stuff’ – but the short Irish leg of the tour was also the only time on tour he was injured and it is possible he stayed on to recuperate ahead of the England Test that followed. His close colleague Billy Wallace certainly took advantage of the trip over the Irish Sea to visit, for the first time, his paternal grandparents in Derry.

The close connection was revived, however, on the centenary of that tour in 2005 when a high profile party of New Zealanders – Sir Brian Lochore, Tana Umaga, Conrad Smith, Jerry Collins, Joe Rokocoko and others – visited Gallaher’s birthplace in Ramelton, took a coaching clinic locally and were then the guests of the local Letterkenny Rugby club who had decided to name their new ground in his memory.

A memorable rugby day was had deep in GAA heartland and an important link forged by Letterkenny who now have the contacts to send promising players to New Zealand to get invaluable experience. Not to be outdone, Ramelton have now named a sculpted garden area in the town in Gallaher’s memory.