Paul Rees reports on why fears of crowd trouble at the World Cup in France are beginning to increase

SOUTH Africa’s impressive victory over Australia last weekend in Pretoria was overshadowed by fighting in the crowd. A few hours later in Mendoza, where Argentina were hosting New Zealand, a spectator ran on to the pitch and was tripped up by Sam Cane, the All Black captain. Rugby union has long thought of itself as a sport that does not have crowd issues.

Unlike football, it does not need to segregate supporters (those involved in the Loftus Versfeld punch-up were all South Africans), policing is far more discreet and there is no social media contact between rival fans before a match to arrange a venue for an exchange of unpleasantries.

Football’s troubles are down to tribalism and the idiocy of hatred but in rugby alcohol is the issue. It has been a problem at Wales’s Principality Stadium for some time with fights breaking out between home fans after those constantly getting up for pints of beer during the game and forcing those around them to stand up were confronted.

Last year, an 80-year old fan was injured when he found himself in the middle of a fight in the ground. Spectators have related how they have had to leave early after being caught up in drunken behaviour, soaked with beer or inadvertently struck.

One former Wales international told how he and a friend had to vacate their seats after spectators behind them drenched their seats with beer. They sat in the dry on the steps at the end of their row only to be told by a steward they had to return to where they were seated or leave. When they explained why they had moved, they were met with a shrug. They left. The clowns who were unable to hold their drink would no more have been able to identify the Wales great than they would Romania’s foreign minister.

Twickenham has had similar problems but at a time of financial incontinence, the game needs every penny, even if spending it causes such disruption to those who want to watch a game they paid so much to be at.

Rugby in Australia is fighting for its future, not that that explains some behaviour of fans in recent years. Last year, Eddie Jones, then in charge of England, had a confrontation with a fan after the series victory in Sydney. He was called a traitor and confronted the abuser.

Four years earlier on the Gold Coast, players were caught up in a physical confrontation with spectators after losing to Argentina. One fan had to be dragged away, which was just as well for him as the two players he was threatening were substantially taller and wider.

Earlier this year, three players were taken to hospital in South Africa after being attacked with broken bottles during a club game in Eastern Province. Home fans, incensed after a defeat, invaded the pitch and their club had its home fixtures suspended for the rest of the season.

“Historically, rugby creates its own problems because of the embedded drinking culture surrounding the sport,” said Supt Mark Cleland in 2017 after problems in Cardiff. “As a result, we often see poor behaviour after a match.” That is when opposing fans feel threatened rather than during a game.

Tribalism fuelled Welsh rugby in the days before regional rugby. The rose-tinted view of rugby being a sport that values friendship and the spirit of the game was not born in its early years.

The game in Wales was known for its violence on and off the field. “Amiability could be at a discount when ritual derbies provoked fighting among players, among spectators, and between both,” wrote David Smith and Gareth Williams in their history of the Welsh Rugby Union, Fields of Praise. “The referee suffered frequent abuse and assault from enraged followers, who symbolically regarded him as some sort of scapegoat for the rent collector or the whipper-in.”

Teams in the early years changed in pubs in a town rather than at a ground and players and referees had to run a gauntlet after a match. Many was the time a referee was thrown into a river and players pelted with mud and stones.

Smith and Williams recorded an event in the 1890s when Llangennech played at Tenby. “It was not a match noted for being a kid glove affair. After the game, Llangennech’s players and supporters were hounded and fought all the way to the station and into the (train) carriages, some of which were severely wrecked.

“When Llangennech, 28 years later, applied to Great Western Railway for travelling facilities to Pembroke, they were refused because the previous excursion had been the costliest on record.”

The 1892 international between Wales and Scotland in Swansea saw the English referee Jack Hodgson physically attacked after angering some in the 12,000 crowd with his decisions, including one to disallow an Evan James penalty.

Wales’s captain Arthur Gould, who was knocked to the ground in a melee after the match, ensured Hodgson reached his hotel safely following the home side’s 7-2 defeat. The response of the Welsh Football Union (as the WRU was then known) was to express its regret at the conduct of the St Helen’s crowd but it also wrote to the RFU asking it to “appoint competent men to act as referees in international matches.”

Referees seemed fair game then, but not in a more image conscious age. There was uproar when the Scottish referee Ken McCartney was kicked by a spectator as he tried to leave the Stradey Park field following Llanelli‘s defeat against New Zealand in 1989.

In 2002, seven years into the professional era, the Irish referee David McHugh was steadying a scrum a King’s Park in Durban when a burly spectator, whose South Africa replica jersey was a few sizes too small, came on to the field and wrestled him to the ground.

As his not inconsiderable bulk fell on McHugh, New Zealand’s flanker Richie McCaw intervened, along with the home captain AJ Venter, ‘rhe spectator, blood pouring from his nose, was overpowered by stewards and marched off the field, followed sewn minutes later by McHugh on a buggy holding his left arm.

McHugh suffered a dislocated shoulder. The spectator, one Pieter van Zyl, had lost his sense of reason after New Zealand were awarded a penalty try and the Springboks were denied a try because of interference off the ball. He was fined some £1,000 after admitting common assault and banned for life from matches organised by the South African Rugby Union.

After the court hearing in Durtxin, van Zyl was anything but contrite. He boasted that he had received overwhelming support from the public which he had not expected and found it overwhelming. As he spoke, his lawyer stared furiously at him and drew a finger across his throat.

Van Zyl’s just ification was that the whole of the stadium was angry with the referee and he decided to do something about it “Referees around the worid think they are bigger than the game and they’re not. Fans like me are what rugby is about”

The fact that the game would not exist without referees was lost on him and so he did not bother to consider a consequence of his actions, deterring someone considering taking up the whistle.

The incident prompted a review into how someone could get on to the field while the game was going on despite 419 stewards being present Action was promised throughout the game, but in 2021 at the Principality Stadium a spectator invaded the field of play when Wales were mounting an attack and forced Liam Williams to check his run when he was bound for the try line.

The drunk did not enjoy the overwhelming support of his compatriots. He was booed off the pitch and had beer thrown at him. It turned out he, a club player, clambered over the barriers after a £20 bet with friends and potentially cost Wales victory in a close match.

A 2007 study into the behaviour of rugby union crowds found that team success but not failure may increase aggression among supporters, and that aggression, not celebration, drives post-match alcohol consumption. Losing and drawing decreased happiness but winning did not increase it.

“Better understanding of pathways to violence in these circumstances will pave the way for more effective prevention and management strategies,” it concluded. The survey was conducted at international stadiums and the fans were all men, divided into three categories depending on whether their team had won, lost or drawn.

Crowd violence was a factor behind rugby union’s exclusion from the Olympics for 92 years from 1924. The final that year was held at Stade Colombes in Paris where France took on the United States before a crowd of 30,000. They started booing two minutes in when the home side’s star turn Adolphe Jaureguy was floored by a hard tackle and left the field on a stretcher with blood pouring from his face.

As the match went on, the French crowd threw bottles and rocks on to the field, aiming at the American players and the match officials, and fights broke out in the stand. A United States reserve, Gideon Nelson, was hit in the face with walking stick and knocked unconscious and fans invade the pitch at the end of a match the Americans won 17-3 to clinch the gold medal.

The French team protected their opponents who were escorted to their dressing room by gendarmes. At the medal ceremony, the United States national anthem was drowned out by booing and hissing. The 1928 Olympics was held in Amsterdam but the International Olympic Committee turned down rugby’s request to take part, citing its desire to include more individual and women’s events, but mindful of the battering its image took at Stade Colombes.

The World Cup is being staged in France this autumn. The tournament has not been without incident. In 2003 when South Africa played Samoa in Brisbane, a drunk Samoan supporter ran on to the pitch and tried to tackle Louis Koen around the legs as the Springbok was attempting a kick at goal. His attempt was late and as Koen kicked for the posts, he inadvertently put his boot to the head of the spectator who was knocked unconscious and led away on a stretcher.

There have been occasions when fans have been on the receiving end. The former Cardiff wing Gerald Cordle more than once reacted to fans who shouted racial abuse at him. One, at Newbridge, opted to make his way out of the ground in a hurry rather than answer to the understandably irate player.

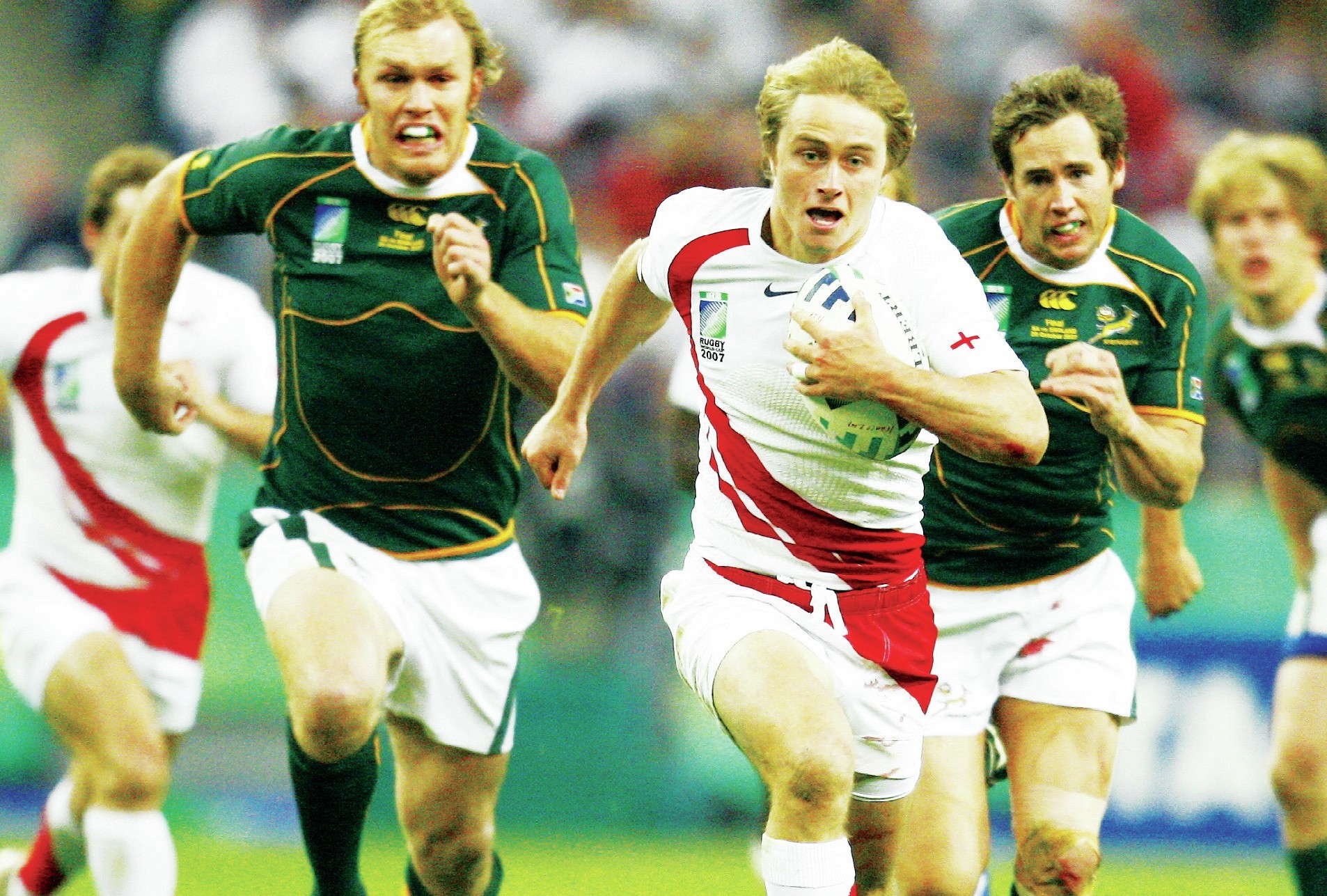

And in 2007, the Ireland forward Trevor Brennan, below, playing for Toulouse against Ulster in the then Heineken Cup, ran into the stand and assaulted an Ulster fan he claimed had been mocking the standard of the bar the player co-owned in the city. Brennan was banned for life with the punishment later reduced to a five-year suspension.

Last month, a club match in South Africa was abandoned at half-time after a visiting player was stabbed by a spectator during the interval and taken to hospital. The fan was arrested after being chased by players and club officials and the referee called off the game in Borland saying he was too traumatised to continue.

SARU’s president, Mark Alexander, was left to reflect on a third case of crowd trouble in as many months, one of which saw a referee assaulted. “This type of behaviour is disgraceful and unacceptable,” he said. “At the heart of rugby is a unique ethos which it has retained over the years.

“Not only is the game played to the laws, but within the spirit of the laws. Through discipline, control and mutual self-respect, a fellowship and sense of fair play are forged, defining rugby as the game it is. Living the values of the game both on and off the pitch is of paramount importance.”

The irony is that the fellowship Alexander referred to is built on violence. There may now be zero tolerance on foul play in a game where, not that long ago, a punch would not merit a talking-to from a referee never mind further action, but as was seen in Pretoria last weekend, physicality is at its heart and the Wallabies were smashed backwards.

Any crowd trouble is not down to rival fans clashing but, in most cases, too much alcohol. Back in the day, matches kicked off early in the afternoon and with the majority of spectators standing, there was little demand for refreshment.

Today, matches start much later: the World Cup opener in France starts at 9.15pm local time and 17 of the pool games kick off at 9pm. The sale of alcohol is important for unions because it provides income but many, including England’s World Cup winning coach Sir Clive Woodward, have complained that Twickenham has become like a giant pub with a number of spectators regularly getting up from their seats during a match to top up, or the reverse, causing friction with those who want to watch the game.

The audience is changing. In Wales, where tickets from internationals were sold through clubs, many now go on general sale. The values Alexander referred to have become diluted and the Press box at the Principality Stadium is not the safest place to be at the end of a match Wales have lost.

After England had lost to Australia at Twickenham in the 2015 World Cup, and so exiting the tournament they hosted, a fan in an upper stand let go of a full pint of beer. It landed in the Press box, close to the hooker in the 1991 final against Australia at the ground, Brian Moore. A strength of rugby union is that players are generally deferential to the referee, something that is ingrained at a young age. They set an example, one that has so far survived an age where failure can mean the loss of jobs.

Yet rugby’s past should not be regarded as a sunny upland. When Swansea played Cardiff in 1892, Smith and Williams noted in Fields of Praise that “the referee was attacked after a very rough game in which he first gave and then, upon appeals from Cardiff, disallowed a drop goal.

“Stones thrown at the referee took out the eye of a bystander. Newspaper offices were stacked for printing the ‘correct’ score. The WFU later upheld an appeal by Swansea and reversed the referee’s decision on the grounds he should not have changed his mind once made up.” It took a special general meeting to overrule the appeal.

Clubs were severely warned for not controlling the violent behaviour of supporters. Aberavon’s ground was closed for eight months in 1899 after a mob chased the referee and Stradey Park was shut for four weeks after crowd trouble.

In 1921, when Wales played Scotland in Swansea, the crowd numbered 62,000 and bulged on to the field. Play was suspended for 12 minutes and reporters noted several discreditable features, including fans who took bottles of beer into the ground, throwing the empty ones all over the place. A number, mostly women, left in a hurry after being soaked or nearly hit by a flying bottle.

The more things change……

You must be logged in to post a comment Login