The man in Seat 54, Row U of the middle tier of the East Stand looked down on a familiar figure darting along the touchline right in front of him. Brynmor Williams knew the Welsh substitute wearing the number 21 better than any man on the planet. What the old scrum half did not know was that within seconds the young one would extend the family tradition for out-witting England.

The man in Seat 54, Row U of the middle tier of the East Stand looked down on a familiar figure darting along the touchline right in front of him. Brynmor Williams knew the Welsh substitute wearing the number 21 better than any man on the planet. What the old scrum half did not know was that within seconds the young one would extend the family tradition for out-witting England.

When Lloyd Williams dug Wales out of trouble with that deft touch of his left foot for another scrum-half, Gareth Davies, to score between the posts, his father had left his seat. He had taken off in a joyously hopeless attempt to defy gravity the way the Cuban Javier Sotomayer did more than 20 years.

“I jumped so far out of my seat that I must have got close to the world high jump record,” Williams, senior, said. “People all around were hugging and kissing me. It was lovely but most of all it was lovely for Lloyd because he executed it to perfection.”

Towards the end of a night when Wales toiled to find any space, their emergency left wing suddenly found an ocean of it. In doing so, amid the turmoil of a widely dislocated back division, England succumbed, as they have done down the decades, to Welsh nous.

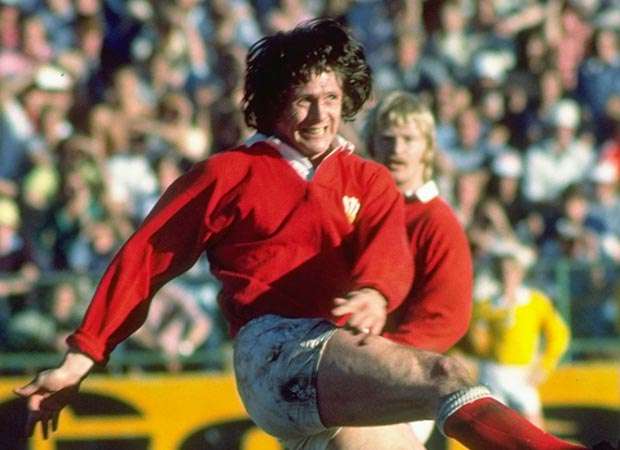

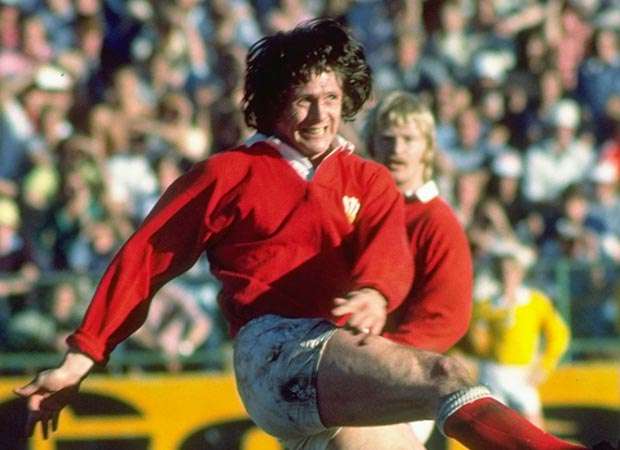

Williams’ father started the family business of putting the skids under England way back before the birth of his elder son, engineering a winning late penalty for Wales at the start of the 1981 Five Nations. He did so by luring an opposition three-quarter into an offside position with the oldest trick in the game.

His victim is rather better known today as the only British coach to win the World Cup – Sir Clive Woodward. Bill Beaumont’s England had pitched up at Cardiff Arms in mid-January for the opening defence of the Grand Slam title they had won the previous year.

They were leading 19-18 and within sight of the final bell when Williams threw a dummy from the base of a scrum in front of the posts. The pretend pass, leaving the ball firmly lodged in the back row of the scrum, caught Woodward in the trap and gave Steve Fenwick the kind of penalty he never seemed to miss.

Williams, a Test Lion while playing second fiddle to Gareth Edwards, was only doing what every scrum half did to gain an advantage. Despite that, England fans accused him of gamesmanship.

“I must have had five-to-six hundred letters from disgruntled England supporters,” Brynmor said. “But what I did was allowed under the laws of the game as they were then. Had I touched the ball that day, Wales would have lost so it was very pleasing to have played some sort of role in the win.”

The practice has long since been outlawed but at the time it was perfectly legitimate. It cost England the possibility of achieving a feat which back then had not been achieved since the Twenties.

Beaumont, now chairman of the RFU, was not amused. “Not only had we lost the game, I also felt I hadn’t played particularly well either,” he recalled in his autobiography. “We had thought we were the bee’s knees but, clearly, we weren’t and all hope of back-to-back Grand Slams had been blown right out of the window.”

The stakes last Saturday were infinitely higher, the stage widened from the confines of the old Five Nations to one of global dimension.

The manner of a win that will be talked about for as long as the game is played brought thrilling reaffirmation of an old truism – that Wales produces more instinctive rugby players than England.

And they have a knack of selling England dummies like nobody else. Ask Sir Clive.

Latest News

Pete Ryan: Bridgend’s College Pathway

Latest News

Jacques Vermeulen: I must prove myself again

You must be logged in to post a comment Login