Jack’s philosophy? Win today, win tomorrow…

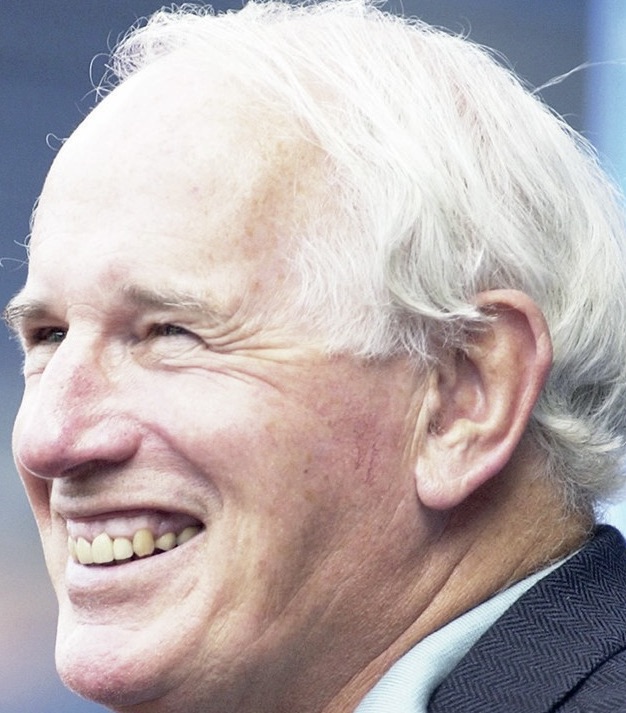

READING - SEPTEMBER 1: Bath Director of Rugby Jack Rowell looks on during the Zurich Premiership match between London Irish and Bath held on September 1, 2002 at the Madejski Stadium, in Reading, England. Bath won the match 24-22. DIGITAL IMAGE. (Photo by John Gichigi/Getty Images)