By Peter Jackson

Charlie Faulkner will never forget his international debut, how he stood toe-to-toe against the All Blacks and slugged it out for the full 80 minutes.

The Newport steelworker had taken time off from the blast furnace to make the Wednesday afternoon appointment and the Welsh Rugby Union showed their appreciation by ensuring that the uncapped prop went home in the same bareheaded state as he arrived.

New Zealand, then as now, represented the acid Test. The appearance of a team featuring Bryan (‘Bee-Gee’) Williams, Sid Going, Tane Norton, Ian Kirkpatrick and Grant Batty duly packed the Arms Park to the rafters, a Test match in every sense only for the authorities, in their arcane way, to decree that no caps would be awarded.

Having made a decision for reasons that the players still cannot understand five decades later, the same WRU then did a volte face and decreed that they would award caps on two occasions for exhibition games against the Barbarians.

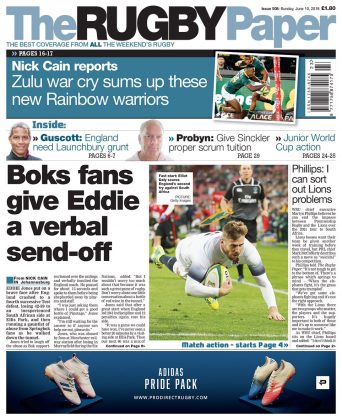

They did so again last Saturday night, declaring their Washington stop-over against the Springbok Reserves an official Test match, thereby elevating it to a status it didn’t deserve. Faulkner watched from afar in a state of rising bemusement.

It took him back a very long way, 44 years to that afternoon in late November 1974 as the newest component of what would develop into a Welsh team whose greatness can be gauged by what they won over the ensuing five years. Wales lost, as they still do to the All Blacks, not that anyone could point a finger at the new prop despite his exposure to a tighthead as powerful as Kent Lambert. Faulkner was still there at the very end because the thought of not lasting the full 80 would never have entered his head.

He had done himself and his country proud, but that didn’t prevent him from being denied the crowning glory that night of receiving his cap amid the traditional pomp and circumstance of the post-match dinner. It bothered him all the way home.

“Don’t get me wrong, I felt very pleased and relieved not to have let anyone down,” he said. “That was one of the best Welsh sides and I was proud to be a part of it. But I was concerned because although I had played for Wales, I still didn’t have my cap to show for it.

“I remember thinking to myself: ‘I hope they pick me for the next game’. There was no guarantee they would. I didn’t want to think I’d get so close and finish up as far away from a cap as when I started out.

“The next game wasn’t until the start of the Five Nations in the New Year – France in Paris. It seemed a long way off and there was always the risk of getting injured or the selectors changing their mind.”

The fact that he had served an unusually long apprenticeship may have heightened his uncertainty. The more senior players then tended to be hyper-sensitive about their age, acutely conscious that the Big Five selection panel considered 30 as not far off the knacker’s yard.

The newcomer’s official age, as stated in the match programme, put him at 29 at a time when it was not unusual for players of a certain vintage to be advised by the team’s inner circle to think about shaving a couple of years off their real age.

No matter whether he may, or may not, have been anything between 31 and 33, Faulkner’s anxiety proved unfounded. Wales picked him as one of six new caps against France in January 1975, a match famous for the Test baptism of the Pontypool front row en masse and the youngest of the trio, Graham Price, galloping 75 yards for a try in the last minute.

By the time he finished four years later, Charlie had caught up for lost time in a way he could hardly have dreamt of, his 19 caps amounting to a glittering array of trophies – two Grand Slams, four successive Triple Crowns and four Championship titles.

Now, of course, a prop is rarely programmed to last for 80 minutes. As a breed they tend to build a stack of caps from the bench, a feat performed so successfully by Ollie le Roux that the ‘Baby Elephant’ started only eleven of his 54 Tests for South Africa.

As a player during a pre-substitute age when hookers like Alan Simpson of Sale and Roy Thomas of Llanelli spent their best years sitting on international benches without ever getting a Test between them, Faulkner believes the cap has been cheapened by matches like the one in Washington.

“You can’t help feeling that sometimes they get caps without really earning them,” says the senior member of the famous ‘Viet Gwent,’ now in his Seventies. “I think they are devaluing Test rugby as we know it and I’m certainly not the only one who thinks like that. The whole thing’s being undermined.

“I think the powers-that-be should look at it and make sure that Test rugby gets a bit more respect. In my day you had the full 80 minutes to wear your opponent down and gain an advantage for the whole team.

“Now they’re able to sub one complete front row for another. I don’t like it. Scrummaging is very different now that scrum-halves are allowed to put the ball virtually straight into the second row. Some props have little or no technique.

“Gareth Edwards always said he played behind a great pack in the Seventies. Channel one ball or channel two, it made no difference. Either way we gave him a good platform to work on.

“As a pack, I don’t think we got the accolades we deserved. The backs got them all instead. They always show ‘Benny’ (Phil Bennett) scoring the try that clinched the Grand Slam against France in Cardiff but what they don’t show is the pack making it possible by shoving the French off their own ball in the 25.

“And that was some French pack, full of great players. I was up against (Robert) Paparemborde and after the match he invited me to his wedding. I wasn’t able to go but I made sure I sent him a card. I wanted to do the right thing by him because it was an honour to be invited.”

The Rugby Paper is on sale all year round! Keep abreast of the June internationals and your club’s activities in the off-season by subscribing: http://bit.ly/TRP-Sub