Brendan Gallagher continues his series looking at rugby’s great schools

AMPLEFORTH’S ROSSLYN PARK DOUBLE OF 1989: Open: Pool: Yeovil 42-6; Malvern 42-0; RGS Guildford 37-0; John Fisher 20-10; R5: Stade 18-6; QF: Plymouth 8-4; SF: Neath 10-6; Final King’s Worcester 38-0. Festival: Pool: Kingswood 16-6; Duke of York RMS 26-0; Monkton Combe 30-8; Oakham 22-0; R5 Lord Williams 34-4; QF: Rugby 14- 10; SF: Byranton 12-4; Final Cheltenham 12-6

AMPLEFORTH’S ROSSLYN PARK DOUBLE OF 1977: Open: Pool: Chiswick 44-5; Ashville 24-7; Dover 30-0; Gresham’s 18-0; R6 Hurstpierpoint 12-6; QF: Loughborough GS 27-0; S/F: Plymouth 11-0; Final: Sherborne 16-6. Festival: Pool: St Michael’s Leeds 20-0; St Edward’s Liverpool 10-6; Hampton GS 10-6; Q/F Gunnersbury 20-6; S/F Coleraine 16-7; Final King’s Macclesfield 12-3

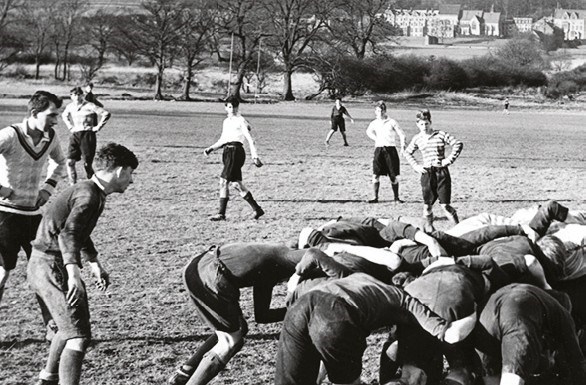

YOU only have to visit Ampleforth College briefly to appreciate that rugby is a way of life in the bracing airs of north Yorkshire.

Former pupil Lawrence Dallaglio, on his first day there, claims to have counted 27 pitches in the Ampleforth Valley while for decades the splendid Ampleforth Journal, rather than include a sports section, settled for a hefty chapter entitled “Rugby and other outdoor activities”.

If Ampleforth, founded by Benedictine Monks in 1802, wasn’t one of the foremost centres of Catholic learning in Europe you would say rugby was the prevailing religion.

Great unbeaten fifteens have dotted the school’s history for over a century or more and last season’s side, if not absolute vintage, was very promising with 12 victories in 17 games on their perennially strong circuit and a place in the National Bowl final after an outstanding 27-5 semi-final win over old rivals St Edward’s Liverpool.

Coach Will James, the former Wales lock, had high hopes for the big showdown at Allianz Park but their game against Worthing College had to be cancelled as Covid-19 brought the season to a premature end.

Ampleforth seem on the up again but what James, along with other coaches and indeed year groups at Ampleforth, have to live with is the mighty achievements of the past, particularly in the 1970s, 80s and early 90s when Ampleforth were a force of nature under the coaching of former England full-back John Wilcox and Frank Booth.

Wilcox was a fearless fullback with Quins, England and the Lions and not a man to be trifled with. He was a Sandhurst graduate and a boxing Blue at Oxford as well as a star of the XV. He arrived at Ampleforth initially to teach languages but the rugby team soon became his pride and joy.

Ampleforth became not only the fittest school side in Britain, they were probably the fittest rugby side in the British Isles bar none. It became part of their DNA.

“The fitness programme there was as hard as anything I’ve ever done,” recalls Dallaglio.

“I learned early on that the human body can be pushed very hard indeed. Not only did we play or train just about every day but the Valley covers a vast area and it was a major hike walking to and from the various grounds. Looking back, without even noticing it, that being on the move constantly was building in another extra level of fitness “The facilities, levels of fitness and coaching were incredible. The first XV would practice lineouts and penalty moves every day for 30 minutes.

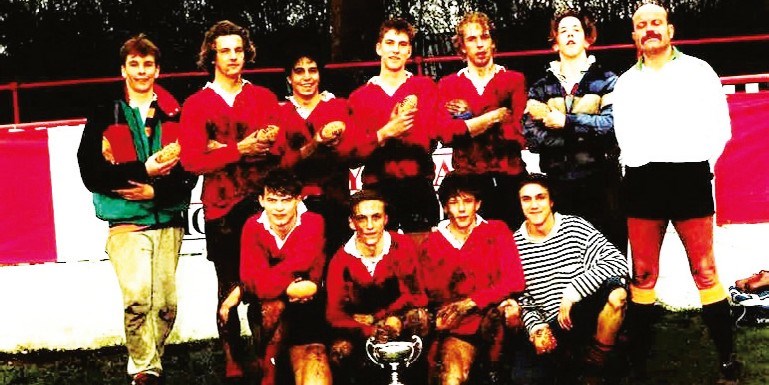

I don’t ever remember seeing them lose a lineout.” On the back of that incredible fitness Ampleforth pulled off one of the great feats of modern day rugby. During four rainy, cold, blustery days in March 1989 their Sevens side won both the Open and Festival tournament at Rosslyn Park, a test of endurance which encompassed 16 games on the bounce.

It was the occasion that Dallaglio, just 16, announced himself to a wider audience and hinted at an exceptional career ahead although he was by no means the stand out for Ampleforth.

A squad packed with talent included England schools’ caps Paddy Bingham and Richard Booth who were both born Sevens players, future Ireland scrum-half Guy Easterby and flying wing Dario Cusado who was to win a Cambridge Blue.

Other names are less well known but Nick Hughes, for example was a hooker so skilful that, when injury struck on the final day of their marathon four-day stint, he switched to fly-half without missing a beat.

Dallaglio was a newcomer to the Sevens team, a late developer who had only played a couple of First XV games before Christmas. Ampleforth were in the middle of a long unbeaten run at fifteens and just getting into their starting side was a major achievement for a lower sixth. Future international Easterby, whose younger brother Simon was also an Ampleforth product, was another who, like Dallaglio, had to be content with occasional appearances in the senior XV.

Wilcox had recognised a fastdeveloping athletic talent in Dallaglio and when the Sevens season got underway he had no hesitation in promoting him into their squad. Initially he was a reserve, but his moment came at the Mount St Mary’s competition when Wilcox, unhappy with a narrow win over the hosts in a pool game, drafted in Dallaglio. He made an immediate impact and one way or another he’s been making an impact ever since.

“The week playing at Rosslyn Park still lives in my memory,” recalls Dallaglio. “We went down a few days early and stayed at the Old National Sports Centre at Crystal Palace.

We did a bit of fine tuning there, went to watch Nigel Benn fight at the Albert Hall against some guy who he knocked out in the first round (it was Michael Cilambe) and then it started raining and hardly stopped for the entire tournament.

“My role was to win the lineouts and collect the restarts which are pretty important in Sevens. We had some fantastic, experienced, Sevens players and we were on a mission.” Ampleforth’s achievement was rightly hailed and Wilcox offered the opinion that they were the finest ever Ampleforth Seven and their 38-0 win over a strong King’s Worcester in the final of the Open was an alltime high during his time in charge. The only time King’s touched the ball in the second half was to restart after an Ampleforth try. A “tour de force” was Wilcox’s final summing up.

Remarkably though the double had already been achieved once before at Rosslyn Park. By the Ampleforth side of 1977! For some reason that trailblazing achievement always seems to get overlooked, possibly because very few of those involved went on to greater glories.

They were a brilliant team and year group in their own right and we should rectify as far as possible their omission from the Sevens Hall of Fame.

That class of 77, captained by John Macaulay, were a team that attracted almost no attention from the national selectors despite going through the regular season unbeaten.

Come the Rosslyn Park Sevens they were close to perfection with Macaulay and John Dyson running the show.

Less than 12 months later Macaulay was pulling the strings at fly-half for Quins in their John Player Cup semifinal with Gloucester but rather like his school colleagues he soon fell off the radar after that.