Jones is certainly saying the right things and most punters have applauded his first stab at an England squad, but the stark truth is that, one way or another, it usually ends in tears for England coaches.

We have been here many times. Uproar, recriminations, inquests, leaks, sackings, redundancy agreements, gagging clauses. Even the new hope and energy evident at Jones’ squad announcement last Wednesday struck a familiar chord.

Jones is the 17th England national rugby coach and, of course, the first from overseas. A handful left their mark indelibly stamped on England rugby but most made virtually no impact. Some were flattered by their playing record while a couple were unlucky that exceptional wins and achievements got mysteriously overlooked.

We’ve had teachers and businessmen, former internationals and those of very modest playing ability. Almost all were appointed amid some kind of crisis – real or imagined – and departed with a degree of rancour and bitterness. Smooth transitions from one coach to another are not remotely the norm when it comes to England.

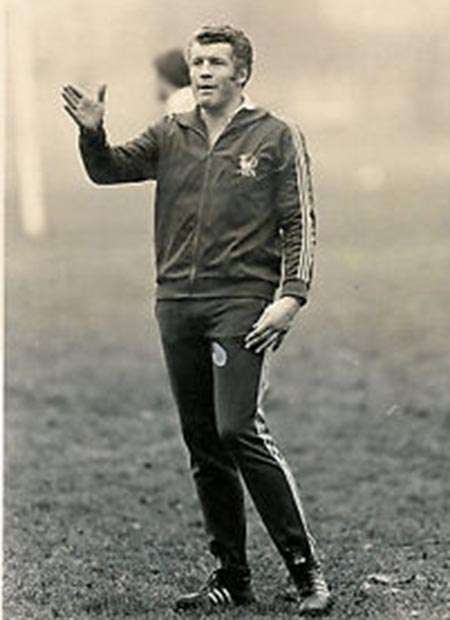

First up was Don White who was always a thinker when playing flanker and captaining Northampton and obvious coaching material if England ever decided to go down that route. The RFU’s inclination was to ignore such dangerously progressive thinking but a run of just five wins in 19 games between 1965 and 1969 caused much concern and the players themselves started lobbying hard behind the scenes. In September 1969 England finally turned to White who, at the suggestion of players desperate to record a first ever win over South Africa, organised a number of Sunday morning training sessions at Welford Road in the autumn by way of preparation.

It was all a bit a slapstick as was the story of White’s first ever session when he delivered a rousing motivational speech which he concluded by smashing fist into palm and saying, “Right let’s go to work, take up your normal positions”. At which point the England team lined up under the posts.

Remarkably, in the very short term anyway, the sessions did galvanise England who claimed a famous 11-8 win over South Africa followed by a notable 9-3 victory over Ireland when Hiller landed two towering drop-goals from just about the identical spot 45 yards out. It was downhill after that, however, with one win in the next nine games and White was soon exiting the scene, to be succeeded by John Elders whose fortunes fluctuated wildly during his roller-coaster ride.

During his 16-game tenure Elders tasted victory only on six occasions and started with the ignominy of a whitewash in the 1972 Five Nations Championship. Yet his England side hit back with remarkable Test wins on the road against South Africa and New Zealand and completed a Southern Hemisphere hat-trick by defeating Australia at home. In his final game they notched a rare victory over Wales.

It was also on his watch that England defied the ‘Troubles’ to play Ireland at Lansdowne Road. Elders, a schoolteacher, later emigrated to Queensland and got involved with the local schools union and had much to do with the early coaching of two young Aussie backs, Tim Horan and Jason Little.

The mid and late 70s were a fairly woeful time for England. The players were there – the team that won the 1980 Grand Slam were all in and out of the side for much of the era – but England under John Burgess and Peter Colston became serial underachievers. In their defence it should be recognised that Wales and France were fielding exceptional teams and that the England selection process did the coaches few favours.

The nadir for Colston was a 27-3, five tries to none, thumping against Wales at the Cardiff Arms Park in March 1979 after which the RFU took the radical step of promoting former England lock Mike Davis, above, directly from the England Schools team, where he had enjoyed much success, to the senior team. Many thought that Leicester guru Chalky White was next in line but Davis got the nod and initially had to overcome a little scepticism from those players based in the Midlands and North.

In November 1979 the North completely outplayed the All Blacks in their 21-9 win at Otley, but England declined to pick Roger Uttley or to make any attempt to persuade Peter Dixon to postpone his retirement which he announced after that game. A week later and England, without that duo, lost 10-9 while the selection of the high risk attacking Les Cusworth at fly-half ahead of the North’s Alan Old was also criticised. Davis recalls: “Budge Rogers was the new chairman of selectors and we had met with (captain) Bill Beaumont. There was a real intent to get the right team on the park. We didn’t quite do that against the All Blacks and we resolved to rectify that. I was still exhilarated after the game because I realised that we should have won, we were onto something. Bill was the same. He was very supportive and said let’s move on quickly here and not lose momentum. Let’s make sure now that we win the Championship.”

And that’s what England did with their first Grand Slam in 23 years, Davis cleverly switching his modus operandi. Whereas he used to instruct his young schoolboy stars in a head-masterly fashion, he now bowed to the weight of knowledge and experience of legendary figures such as Fran Cotton, Tony

England were on the slide again and there was nothing Dick Greenwood and Martin Green could do to stop a disappointing return to the bad old days. Inconsistent and downright bad selection, unfocussed players, poor results. Greenwood, father of Will, bowed out after the 1985 Five Nations which left Green to make his debut on a tough seven-match tour of New Zealand which predictably resulted in two Test match defeats, the second a 42-15 thumping.

Green soldiered on to 1987 but an unruly performance against Wales in Cardiff, which resulted in the banning of four England players, and a distinctly average campaign in the opening World Cup saw him depart, eventually to be replace by Geoff Cook.

The new man was very different to those who had gone before. Cooke was a decent enough player although never international class but was all over

cutting edge sports science and managerial techniques. He knew his mind and was decisive. Cook could be edgy and confrontational and England took their cue from him, generally with great success.

Cook started cracking the whip and getting England fit for purpose. His controversial selection of young Will Carling as captain was nonetheless inspired even if it was the old lags who still exerted much influence. England improved dramatically but blew a Grand Slam in 1990 before safely delivering the goods in the 1991 Championship. They even reached the 1991 World Cup final where they lost to Australia.

These were halcyon, revolutionary, days. After the 1991 World Cup England seamlessly made a major switch with Dick Best effectively coming in as the head coach and Cook becoming what we would now call a manager although that understates his continuing role and influence.

Initially England didn’t miss a beat and their 1992 Grand Slam was hugely impressive and if the 1993 Five Nations was hit and miss as a great team ran out of steam, it’s difficult to argue with a win over New Zealand in November 1993 and a 32-15 victory over the Boks at Loftus in June 1994.

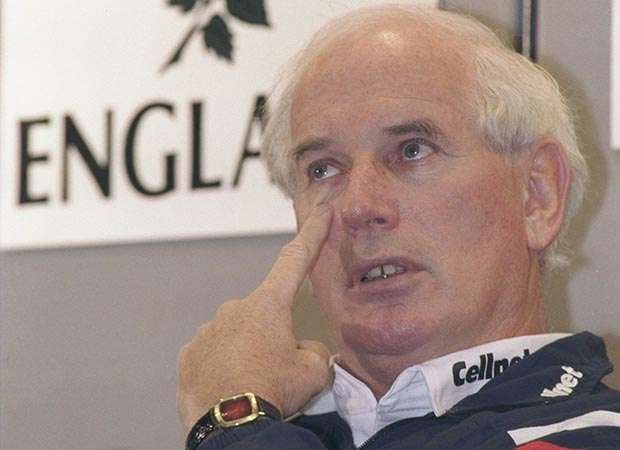

The outspoken and confrontational Best wasn’t everybody’s cup of tea and found himself surplus to requirements after that South Africa tour in 1994 when Bath boss Jack Rowell, above, took over. Harsh on Best given his record, and that Rowell could be just as bloody minded and vociferous as Best, but English rugby was in thrall with Bath rugby at the time. The feeling was that if the national team could play more like Bath they could be world beaters.

Regardless of how he was appointed, Rowell was certainly a coach who deserved to operate at Test level at some stage. England were a very solid and competitive outfit during his stint in charge even if he never got the national team playing like Bath.

Under Rowell, England won the 1995 Grand Slam and, in my opinion, had they played anybody other than New Zealand in the 1995 World Cup they would have reached the final. The axe finally fell after they finished runners-up in the 1997 Five Nations and had a 1-1 series draw with Argentina with a very makeshift team in a Lions year. The logic behind his dismissal wasn’t entirely clear but it rarely is with England coaching appointments

With Cotton and RFU chief executive Francis Baron supporting Woodward, he was allowed to make early mistakes, a middling 1999 World Cup campaign was tolerated and sympathetic noises made when three Grand Slams on the hoof were blown in 1999, 2000 and 2001. Just for once time didn’t seem to be pressing and money was, almost, no object. The result, ultimately, was a staggering run of 14 games undefeated against the SANZAR giants, world number one ranking and the World Cup trophy.

But even that ended in acrimony with the RFU unwilling to take on board even more radical proposals from Woodward who felt England needed to regenerate again, immediately, if they were to defend their trophy.

Andy Robinson, his loyal number two and successful in his own right at Bath, took over, but his reign was ill-starred. He wasn’t blessed with much luck – England were denied a vital win in Dublin by a poor offside call against Mark Cueto when he timed his run perfectly to collect Charlie Hodgson’s kick – but there were also errors of judgement. Who can forget the embarrassing subbing of Henry Paul after 25 minutes of a Test? A miserable run in 2006 saw Robinson depart and Brian Ashton come in, initially as a caretaker.

What to make of the Brian Ashton regime? He was another splendid number two who had struggled when elevated to the main job in Ireland, and England were largely unconvincing under Ashton, not least when massacred 43-18 by Ireland at Croke Park. Yet they overcame an appalling start to reach the World Cup final in 2007 ultimately giving a very good account of themselves.

The RFU weren’t sure whether to credit Ashton or the cluster of senior players who clearly roused England during the campaign. The politics began to get nasty behind the scenes and, within a year, Martin Johnson, a glorious World Cup winner but a man with zero coaching or selecting experience, found himself in charge. England do move in mysterious ways sometimes.

Johnno actually did better than he is given credit for and during his last calendar year in charge England won ten out of 13 internationals and won England’s last Six Nations Championship. Alas, all that was forgotten in the wake of RWC2011, as much for the off the field headlines as an average campaign that ended with a lacklustre quarter-final defeat against eventual finalists, France.

The leaked reports of the post tournament inquests weren’t very flattering – to players or management – but that could be said for most post mortems when teams lose. Whether there was any need for Johnno to resign is a moot point but the politics were still playing out and he wanted no part of that.

Which brings us to Stuart Lancaster who was seemingly appointed as the safe ticket, a schoolmaster to re-establish discipline within the squad and to restore English culture which was perceived, wrongly, as lacking.

Long on work ethic but short on top level experience and instinctive selection skills, there were nonetheless moments when it looked like Lancaster was turning England around – notably that home win over New Zealand in 2012. As the World Cup loomed, however, he became increasingly indecisive and confused as England’s game plan dissolved before our eyes.

Through the long lens of history all this makes for grim, sometimes incomprehensible, reading but at least Eddie can’t say he hasn’t been warned.