Brendan Gallagher delves into some of rugby‘s most enduring images, their story and why they are still so impactful

What’s happening here?

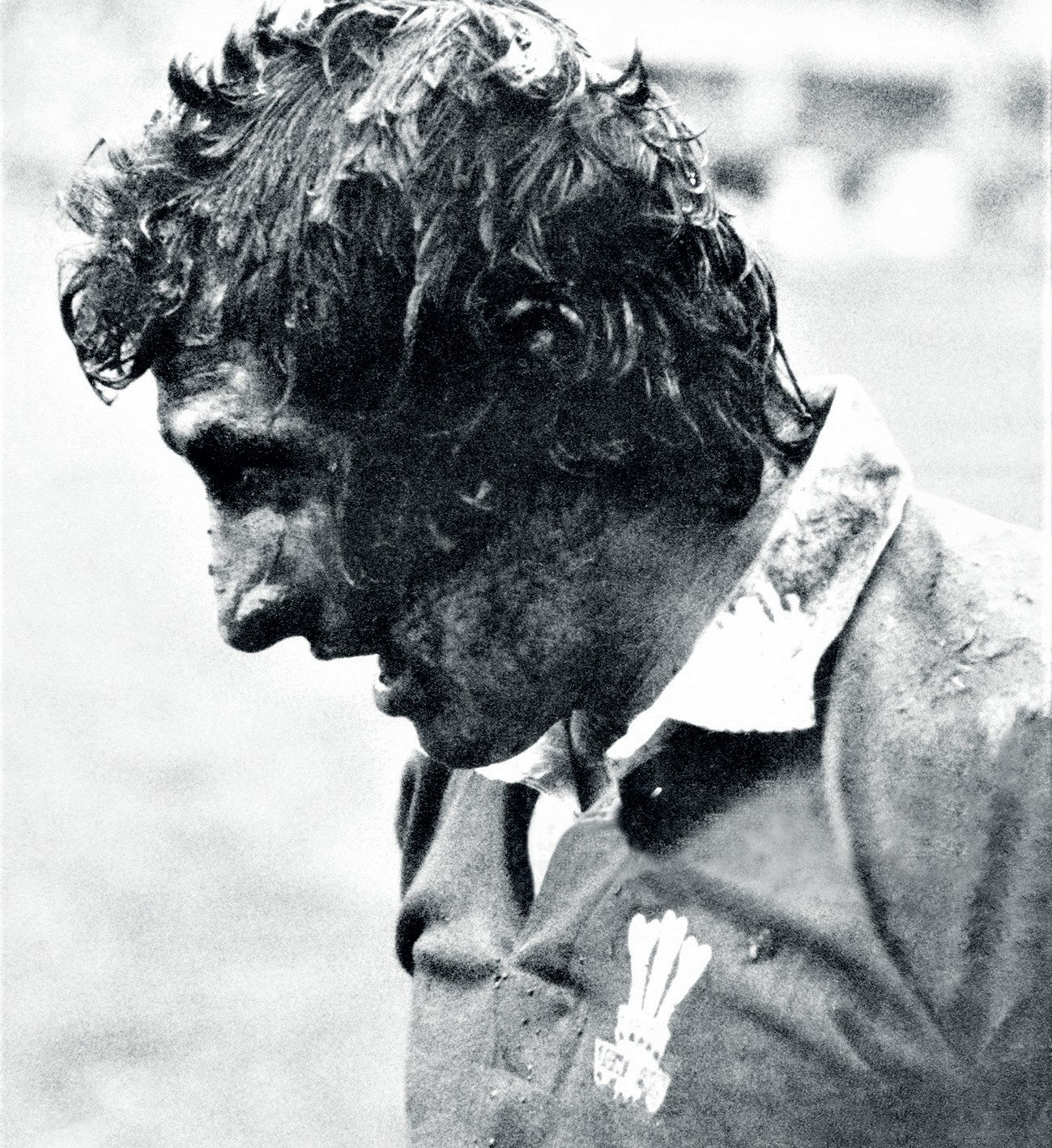

It’s February 5, 1972 at Cardiff Arms Park and Wales scrum-half Gareth Edwards is wearily, but triumphantly, dragging himself back to the halfway line after scoring his second try of the game against Scotland. He is receiving a standing ovation but the Cardiff talisman is still in a world of his own, trying to process what has just occurred.

What’s the story behind the picture?

Wales had won their first Grand Slam since 1952 the previous season but it was surely just the start for a golden generation. The Welsh public, however, had not seen them on home soil since March 1971 when they beat Ireland in the penultimate round of the Five Nations.

In the interim they had been to Paris to clinch the 1971 Slam with a 9-5 win – with JPR and Edwards combining for a sensational winner – and many of the squad had performed brilliantly with the 1971 Lions in New Zealand. There was no full internation- al in the autumn of 1971 and they kicked off the 1972 Five Nations campaign with a 12-3 win at Twickenham and now, finally Wales were back at the Arms Park. The occasion demanded something special.

What happened next?

The scoring of possibly the best and most dramatic individual Five Nations try ever.

Mervyn Davies nicked a Scotland lineout in the Wales 22 and made some ground before setting the ball back with everybody expecting a clearance kick from Edwards. Instead, with his distinc- tive feel for when an opponent might be vulnerable, he exploded out of blocks down the blindside and dismissed powerful Roger Arniel with a pile driver hand-off.

Like a true natural sprinter Edwards then found his ‘mid race pick up’ and also had the presence of mind to look back at one stage and noticed there was very little support from his surprised colleagues. He was on his own, but no matter. An expert Sevens player, he relished high speed chases such as this.

First he had to deal with Scotland fullback Arthur Brown who was still deep in defence, which he did by chipping delicately with his right foot while not breaking stride. It had to be as low as possible – too much height and the covering defence would have time to get back and swamp him – and in fact Brown almost caught it with his fingertips as he lept high.

The ball came down quickly and the only way he could continue his dribble without slowing down was to use his left foot, directing the ball into the far right hand corner of the in-goal area. Now it was ‘just’ an out and out chase and it seemed he must tire and be outdone by sheer weight of numbers with Jim Renwick, covering across on the angle, and Lewis Dick leading the chase. But no, Edwards’ favourite event was the 200 yards hurdles, which requires a degree of endurance, and he was still going like a steam train. Whatsmore he had always known how and when to dive to complete a touchdown, it was his bread and butter and it effectively gave him an extra yard.

Iconic Rugby Pictures: PART 83

Gareth Edwards after his wonder try against Scotland February 5, 1972

Timing his full-length dive perfectly, he got there just ahead of Renwick and such was the force and momentum of his lunge that after getting the touch his body catapulted forward into a somersault on to the muddy cinder greyhound track. If you look at the footage, you can see the overhanging floodlights rocking wildly as the entire stadium started stomping their feet in appreciation.

Why is the picture iconic?

Above all else this hurriedly taken snapshot on a murky, impossibly muddy February is a portrait worthy of a well worked Rembrandt or Johannes Vermeer. World class portraits are much more than just strokes and lines on a canvas. Accurately depicting what somebody looks like, they must plug into their world, convey their personality and struggles, perhaps hint at their back story and get a handle on what makes the subject different and special.

This does all of that and more. The squat, powerful, explosive, almost superhuman Celt capable of physical feats foreign to the rest of mankind; the sharp featured warrior who has just been immersed in battle and covered himself in glory as well as mud; the delicious moment of quiet reflection as he closes the world out for a few more seconds.

As he trudged back, Edwards looked back at the Scottish line on three occasions. “Did I really just do that?”

Then there is the grime and mud, the thickly matted hair, the blackened face and the subliminal image of a Welsh miner clocking off at the end of shift – Edwards was of mining stock. All that is missing is the lamp. You want to climb into this picture and hose him clean, as they did back in the day when the miners re-emerged blinking into the sunlight.

As an added bonus there is the beautiful traditional cotton Welsh shirt of the era – Wales’ best ever jersey with the three feathers proudly displayed.

Footnote: Spike Milligan, a fan in the stands that day, insisted afterwards that they should build a small chapel where Edwards had touched down. It was a modern day miracle.