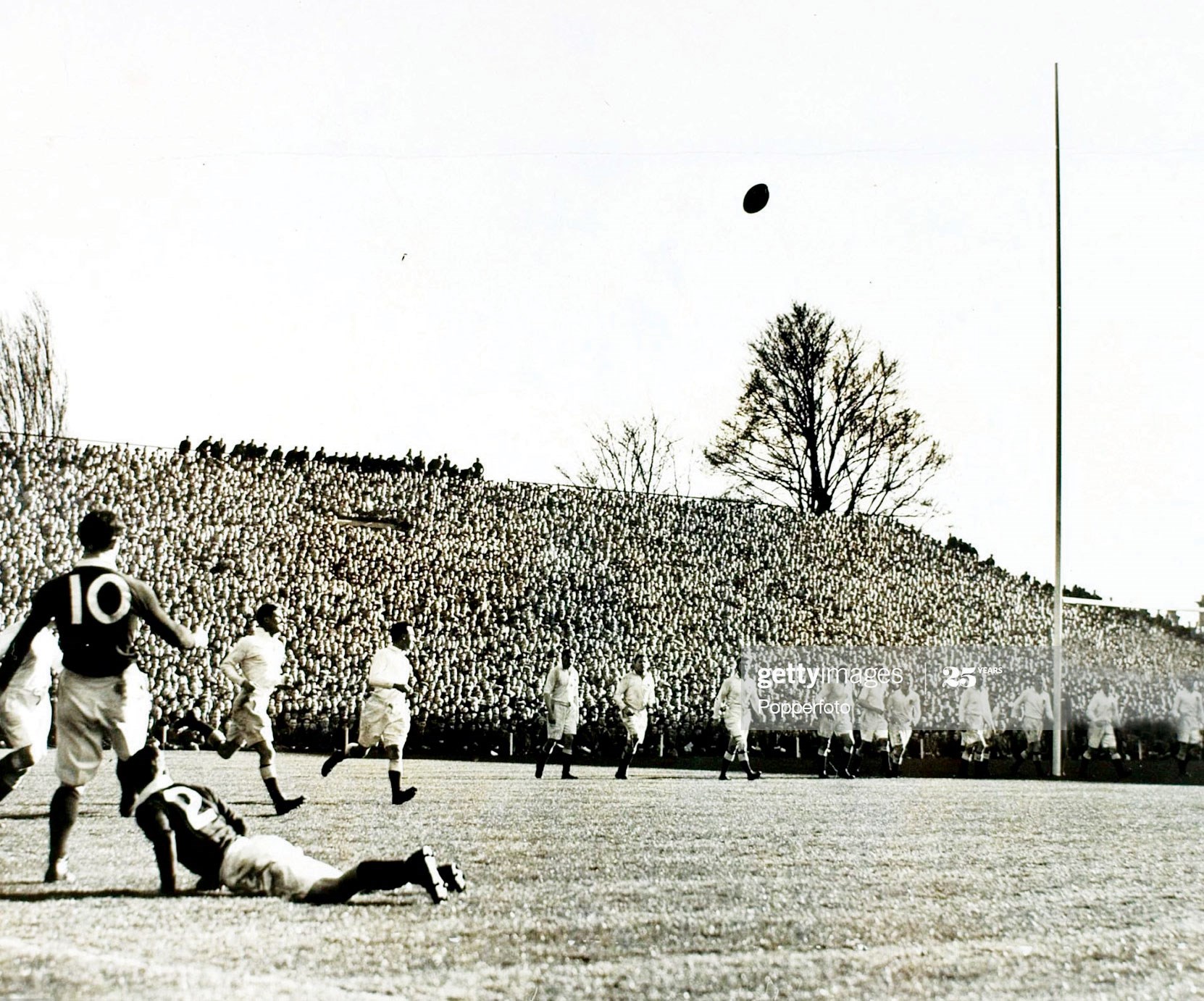

Bird’s-eye view from the old South Stand

Brendan Gallagher delves into some of rugby’s most enduring images, their story and why they are still so impactful

Iconic Rugby Pictures: PART 34

Crawford kicks for goal in famous win at Twickenham March 19, 1938

What’s happening here?

It’s March 19, 1938 and we are at a sundappled Twickenham where, in front of a capacity 70,000 crowd, Scotland are on the way to a famous 21-16 victory against England, a win which also clinched the Triple Crown and the Home Unions Championship. Their inspirational skipper and fly-half Wilson Shaw has just scored a fine try in the corner on the stroke of halftime and I believe this is flanker Will Crawford attempting a difficult conversion from the touchline. The Scots used to number their players randomly in the 30s – the full -back was usually 9 and the half-backs often 1 and 2 and the forwards could be anything – but Crawford was their designated kicker this season. The conversion sailed wide but Scotland turned around 12-9 up and a famous win seemed very much on the cards.

What’s the story behind the picture?

Scotland boasted very useful and occasionally inspired teams in the 1920 and 1930s but had only ever tasted victory at Twickenham once, in 1911, when the home of English rugby was opened. Given the incredible rivalry between the two sides, this was a festering sore for the Scots and something which needed to be rectified. They had last won the Home Unions Championship – France had temporarily been kicked out – in 1933 when they also took the Calcutta Cup, but victory that year had come at Murrayfield.

The Scots wanted to put their best foot forward at Twickenham and in 1938, with a back division including stellar players such as Shaw, Charles Dick, Bill Renwick and Duncan Macrae they were given just that opportunity in perfect playing conditions. In particular they suited the fleet-footed Shaw, a mercurial fly-half seemingly in the mould of Gregor Townsend and Finn Russell who followed decades later. He could turn a match with a moment of brilliance but also attracted much criticism when he overreached himself and it all went wrong.

What happened next?

Scotland marched to a glorious five tries to one victory in what was instantly dubbed “Shaw’s match”. Shaw himself scored two tries as did Renwick –who was to be killed in Bolsena in Italy during World War – while Dick crossed for a fifth. Four of those Scotland tries came in the first half including three in the final ten minutes before half-time. Periods of intense Scottish brilliance have tended to be a theme over the years, you think of their five first half tries in 20 minutes against France in Paris in 1999 or their second half comeback at Twickenham in 2019.

England, enjoying as much of the game territorially, could score only one try through Rosslyn Park wing Jim Unwin, but kept in touch through the excellent goal kicking of Blackheath full-back Graham Parker who landed three penalties while fly-half Reynolds also kicked a dropped goal. England trailed 18-16 nearing full time when Shaw clinched the issue with his second try of a memorable afternoon.

The Scots had not been able to convert any of their tries but Crawford did manage to land two second-half penalties which proved mighty useful come full-time.

Why is the picture iconic?

Action pics from the 30s are few and far between and although this is ‘only’ a touchline conversion it does take you right into a very famous game. You can feel the difficulty of Crawford’s kick, sense the urgency of the shell-shocked England players who are taking a beating and are thinking only of getting to half-time and taking stock.

You can sniff the crispness of a fine Spring day and smell the newly-mown lawn. The pitch is in quite exceptional condition for the era with none of the usual clawing ankle deep mud or long savanna-like grass that reduced pitches to ploughed fields or meadows. It suited Scotland perfectly.

Helping Crawford – if it is indeed the Anglo Scot from Rochester who played for US Portsmouth – with the kick by lightly holding the ball is Macrae and as there are no contemporary reports of wind one can only assume that, in these pre kicking tee days, the ground was too hard to place the ball satisfactorily and Shaw had requested that Macrae lend a hand. Macrae was another dreamy talent, a Gaelic speaker from Balmacara on the west coast, a medical student who less than two years later found himself serving as the medical officer at Stalag VIII-B in Germany after being captured during the Dunkirk retreat.

“You can sense the urgency of the shellshocked England players who are taking a beating”

The March sun is beginning to lower hence the long shadow from the West Stand which is already obscuring some of the England players and it’s fascinating to still see tall trees peering over the old South Stand where the towering Twickenham hotel now stands. We have become so used to the imposing but slightly anonymous concrete bowl of the modern era. A row of spectators sit on the back wall like attentive crows perched on telephone wires.

Twickenham looks a picture which is appropriate because this is the first rugby game the BBC ever ventured to cover live on TV with the action being transmitted to a number of cinemas in West London. Teddy Wakelam did the honours as the commentator, but it was Howard Marshall’s radio commentary that got rave reviews. For the time being radio was still king.

Footnote. Then, as now, Scotland seemed to be harshly treated by the Lions selectors. Despite clearly being the outstanding side of the Home Unions Championship just four Scots toured South Africa with the 1938 Lions a few months later. Shaw in fairness was invited – and would probably have made a big difference – but he couldn’t travel because of work commitments and with Ireland and England boasting nine tourists apiece the Scots had every right to feel aggrieved.