When Tarw put the boot into England Grand Slam

By Peter Jackson

At some point this week, Eddie Jones could do worse than blow the dust off a classic illustration of England’s tendency to go to pieces in Cardiff.

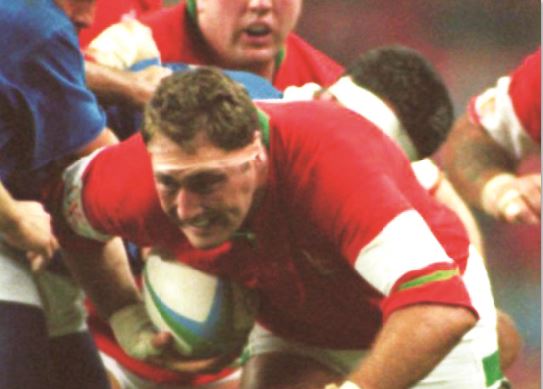

As an Aussie, there is no reason why he ought to have heard of how a bullocking flanker from Carmarthen called Tarw (The Bull) triggered the stampede that brought Will Carling’s double Grand Slam team to grief at the Arms Park.

In that event, any day now would be a good time to pull up a chair and watch it for himself. And with the captain of the beaten team now part of Team England as a ‘mentor,’ Jones only has to look in-house for someone to talk him through what went wrong.

At the very most it will take him less than a minute to appreciate what can happen when one player switches off. Doing so means winding the spool back almost exactly 26 years, to the start of the 1993 Five Nations.

After their clean sweeps of the two previous seasons, in between losing the 1991 World Cup final at home to the Wallabies, England were odds-on to keep winning as they will be against the same country in the same city this Saturday.

Instead Wales, wooden spoonists without a win in 1991 and second from bottom 12 months later, turned the table upside down. They did so thanks to a magnificent rearguard action built around the scything tackles of Scott Gibbs and Mike Hall but, most crucially of all, they did so because Tarw (Emyr Lewis) caught Rory Underwood dozing on the English left wing.

Like so many decisive moves in countless big matches over the decades, Lewis had no idea of the mayhem he would cause. Nor, to this day, does he have a coherent reason to explain why he broke the habit of a lifetime without which Anglo-Welsh history would probably have taken a very different course.

“Nobody gave us a chance,” Lewis says, chuckling at the memory. “England were red-hot favourites and rightly so. There was no-one to touch them. They were head and shoulders above any other team in the Five Nations.

“They were such a ‘professional’ outfit that I don’t think for one minute that they underestimated us. If there had been a degree of complacency, they would not have picked their strongest team.

“Did we deserve to win the match? Probably not. There were no stats back then but had they been available the figures would have been remarkable because all we did was defend for almost the entire match.”

Wales were 9-3 down approaching half-time when Lewis did something he had never done before, to devastating effect. “I’d just come up from a ruck and found myself standing outside Neil Jenkins and Ieuan Evans,” he says. “I expected Robert Jones (Wales’ scrum-half) to pass to Neil on his left.

“Instead he went the other way and passed to me. Instantly I thought: ‘Oh, no.’ There were about three England players marking myself and Ieuan. I put a chip through thinking that Underwood would pounce on it, we’d bundle him into touch and get the line-out.

“In those days forwards didn’t kick the ball. In fact I don’t ever remember kicking the ball in any match, never mind an international. In the back row I’d spent the majority of the time with my head down and arse up competing for the ball. Why I kicked, I still don’t know.”

Lewis’ delicate punt bounced behind Jeremy Guscott in the vicinity of the England 10-metre line and rolled outside Underwood who seemed unaware of any imminent danger. The kick, from his right foot, was weighted so perfectly that Evans hacked it beyond his dithering opponent and made the touchdown with full-back Jonathan Webb stranded hopelessly in his slipstream.

“Leuan was very sharp and Underwood took a long time to turn. Neil (Jenkins) converted and we were ahead by one. Incredibly, that was the last score of the game which again was almost unheard of.”

Ironically, it was a Welshman, Dewi Morris, the Lions‘ Test scrum-half in New Zealand that summer, who came closest to rescuing England. “Morris got held up above the try line,” Lewis remembers. “When you get one of those days when you’re meant to win against the odds, that’s what happens.

“There was a lot of luck involved but there was also a tremendous amount of hard work. Scott and Mike stopped everyone in their path. Their tackling at times had to be seen to be believed.”

Carling will not need a videotape to remind him of the mayhem prompted by Lewis’ speculative kick. As England’s longest-serving captain stated in his autobiography: “It was a situation Rory had faced hundreds of times in his career.

“All that was required was for him to scuttle across and boot the ball into touch. There was plenty of time. He was miles closer to the ball than Ieuan. Unaccountably, and he cannot explain to this day what went through his mind, Rory refused to hurry, only sensing the danger when it was too late.”