As a sportsman, you get the chance to write history every time you take part, whether in the Olympics or your local park. Every game creates its own little piece of history.

As a sportsman, you get the chance to write history every time you take part, whether in the Olympics or your local park. Every game creates its own little piece of history.

With the international game, when something extraordinary happens, like the team Martin Johnson captained winning in New Zealand and then the World Cup in Australia, or Willie-John leading the Lions in South Africa, it becomes set in the stones of history for all time.

At grassroots, players like Sam Dury with over 700 first team games for Ossett may not make it into the nation’s annals, but will forever be a living memory for their clubs.

Eddie Jones had already made history with England by being the first foreign coach; now he has added to that by leading the team to their first series win over Australia. Whatever happens next Saturday in Sydney, Jones is ahead of the game.

Another way Jones put himself ahead of the game was by arranging for the Saxons, basically the rest of the EPS not chosen for Australia plus a few youngsters, to play against South Africa A.

The usual summer for those who are left out of the senior England tour is to remain at home, train hard and keep your fingers crossed that you will be picked for the new EPS come August – but not this time.

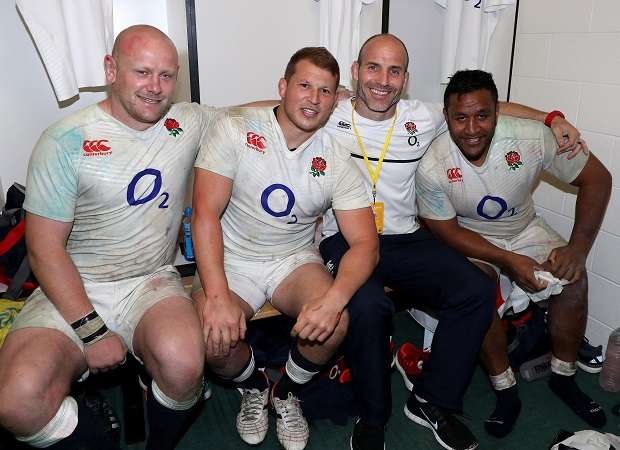

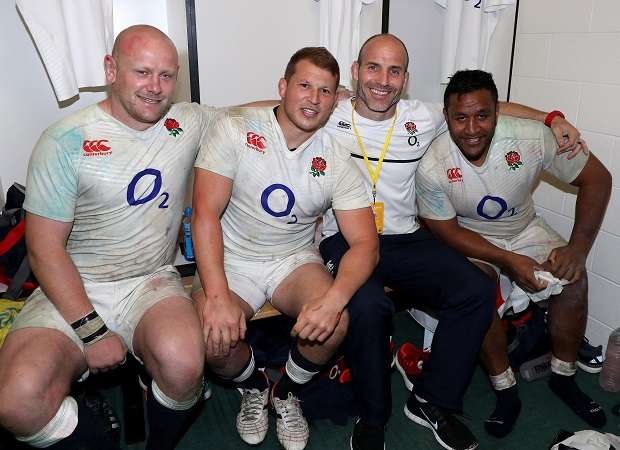

Capped players like Danny Cipriani, Semesa Rokoduguni, Kieran Brookes, Dave Attwood, Tommy Taylor, Christian Wade, Matt Kvesic and Ollie Devoto have been given a chance to show what they can do against international class opposition rather than sitting at home hoping Eddie will select them based on how they played for their club last year.

Jones, by having so many capped players involved in the Saxons tour in his first season as coach, is taking his own view of the history of those players’ selection and rejection to see how many have stepped up training and performance in their efforts to get reselected.

He has been rewarded by a two great wins in South Africa with many players showing that they very much want to be a part of his England squad and the history they will write over the next few years, including the next World Cup.

The buzz Jones has created around the England squad has spread through the whole of the professional game, with players desperate to be part of the international set-up and not just for the extra money.

There is a real sense that Jones has made a difference and that at long last the England team may be on the verge of finally achieving the potential that has been wasted for so many years.

Jones, in the space of just a few months, has achieved what it took Clive Woodward six years to accomplish, which is domination in the minds of at least two of the Southern Hemisphere big three. In attaining the success the team has in such a short time, he has created a desire to be a part of the journey ahead no matter where it leads.

With success, like the players from 2003, you will be forever a part of England rugby history and as Will Greenwood predicted at the final whistle of that World Cup match, get rich! Fail and you would still have had the journey of a lifetime with some incredible highs along the way.

I am always asked about the World Cup final I played in and why England changed the style that had won them the 1991 Grand Slam, all the matches on route to that final and the ‘92 Grand Slam that followed. The thing is, no matter the reason for the change in style, the results can never be altered and so, can never be changed.

Another bit of history that also cannot be changed is the failure of World Rugby to take action on international eligibility rules.

The promise by World Rugby’s vice-chairman Agustin Pichot to look into international eligibility, with the hope of helping to protect the South Sea Islands from having their player base decimated by predatory nations buying up all the young players to play in their leagues, is unfortunately too little, too late.

The Islands and other developing countries have had their best players taken since the dawn of the professional age – and some earlier in the days of the brown envelopes.

The reason they have suffered more than others is simply because at around half the price, it is cheaper to buy an Islander than develop your own young players. This has continued for over 20 years. Although Pichot could, if allowed by the Unions still ravaging the Islands’ academies, change international eligibility rules, it won’t help.

Most of the players are taken not to play international rugby but purely for club or provincial games, and in fact many usually refuse the chance to play for their country as it could cost them their job.

The other thing is that their children who came with them qualify to play for, and feel more at home in, their adopted country.

We now have virtually every major international team in the world with at least one of the Island players’ children. That is a lost generation of players that the South Sea Island nations can ill afford if they are again to compete at the top of the game.