Jackson column: Givvons spun them a golden yarn in Oldham

Alex Givvons left home in Newport’s dockland for a distant town then mightily proud of its self-styled status as the cotton-spinning capital of Europe.

The Welsh teenager was heading towards a new life on the far side of the Rubicon, at a place humming day and night to the sound of 360 mills, one for almost every day of the year. When the last of them closed 65 years later, Givvons and Oldham Rugby League club were still together, inseparable partners in pursuit of a shared passion.

In that stretch of Greater Manchester renowned the world over for the quality of its yarn, he didn’t merely outlive every mill but enhanced the town’s reputation.

Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council decreed that old Alex’s distinctive brand of homespun yarn deserved special recognition and so they named a corner of their town in his honour.

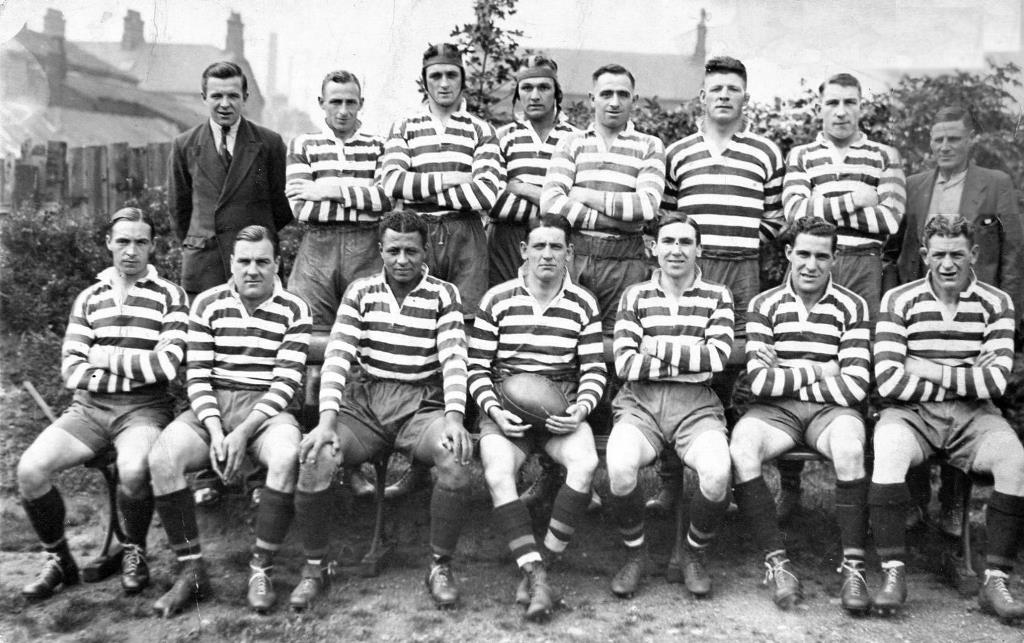

Givvons (pictured third from the left in the front row of the image above) was a frontiersman of West Indian heritage who blazed a trail for a later generation of black Welsh players like Billy Boston, Johnny Freeman, Colin Dixon, Frank Wilson and Terry Michael. Oldham’s scrum-half capture from Cross Keys would become only the second black British player to play Rugby League for his country.

Another native of Newport, George Bennett, has been accorded the distinction of being the first by a matter of months. A stand-off, he joined Wigan from Weston-super-Mare RUFC.

Regrettably, Alex Givvons has remained a prophet without honour back in Wales, just another in the long line of working-class lads ostracised by the Union Establishment for the dastardly crime of taking the northern shilling in order to make ends meet. Their condemnation into a permanent state of Purdah probably explains why few in Union have ever heard of him, let alone his story.

Givvons signed for Oldham on January 19, 1933, by pure coincidence the last day of the Ashes Test in Adelaide when all hell broke loose over England‘s ‘Bodyline’ bowling and Australia threatened to withdraw from the Empire, as it was then, in disgust.

Born in November 1913, Givvons started playing rugby as a nine-year-old at Holy Cross School in Newport. He captained Monmouthshire Schools‘ XV and began his club career at 17 with Pill Harriers, a famous nursery for Newport. Strangely, he never wore the black-and-amber jersey.

“They were very good to me at Rodney Parade,” Givvons told Oldham’s noted historian, Michael Turner. “But they always had a lot of college boys back during the holidays.

“I couldn’t afford to socialise with them and Newport were always the most amateur of clubs in terms of what they would give a player in terms of financial help. I went to play for Cross Keys and had some marvellous times there.”

During his short time at ‘Pandy-monium’ Park, the new scrum-half made an immediate impression, not least on Clem Lewis, fly-half for Wales before and after the Great War despite having been wounded during it. In a column for the Sunday Chronicle, Lewis wrote:

“One of the reasons I visited Cross Keys the other week was to see a dark-skinned scrummage worker, Givvons. Let me say at the outset that on his form against Pontypool he is the biggest discovery I have seen since the war!

“Powerfully built, he has all the attributes of an inside half. His service is a delight and he is a terror around the scrummages. I foresee Cross Keys recapturing their old glories. Chiefly, I see the 18-year-old Givvons become a much discussed figure in Welsh rugby.”

All too soon he would become a much more discussed figure among the dark, satanic mills surrounding the boardroom at the Watersheddings, home of Oldham RLFC.

The raiding party they sent to sign Tommy Egan from Aberavon discovered Givvons on the same highly rewarding weekend.

Michael Turner explains what happened next. “During their stay, the Oldham delegation took in another match, involving Cross Keys and were immediately impressed by a young man at scrum-half.

“On their return, the full committee were informed of the discovery and when they learnt that Huddersfield were also in the hunt for his signature, a decision was taken to offer terms to secure the Welshman’s services without further delay.

“What an alien environment it must have seemed for young Alec. A place where the inhabitants spoke in strange accents and, for the most part, earned their living in magnificent cotton mills with the towering chimneys that dominated the East Lancashire skyline. Even the sport was different: 13-a-side.”

Two days after signing, Givvons made his debut, against Barrow. Three years later, in tandem with his Oldham half-back partner, Norman Pugh from Swansea, the pair helped Wales beat England and France to win the European Tri-Nations’ titles.

After nine years and almost 250 matches as a scrum half-cum-loose forward which made him sound like a latter-day Terry Holmes, Givvons crossed the Pennines to Huddersfield. Six years later he returned whence he came, not to Newport but Oldham.

His work at the club as a jack-of-all-trades and master of most spanned half a century.

He lived in Watersheddings Street, literally round the corner from the old ground before its demolition and coached the A team, improving generations of players who spoke fondly of ‘a courteous almost fatherly man who demanded high standards’.

When he could no longer coach, Givvons became the kitman, always there on match days to ensure everything was as it should be, from the pressure of the practice balls to the temperature of the showers. By then, as Turner noted, ‘a trace of Lancashire had seeped into his Welsh accent’.

Givvons’ service to the club can be gauged by the town’s gradual decline from its ‘Cottonopolis’ heyday. Elk Mill, the last cotton-spinning factory built in Lancashire, had been in production for fewer than five years when Givvons arrived in the town. When it closed in 1998, he and ‘The Roughyeds’ were still a going concern.

Alex Givvons, whose son Alec, junior became a professional in his own right and a top referee, died there on June 14, 2002 in his 89th year. “Well liked, highly respected, a real gentleman,” says Turner.

How they loved him in Oldham and how they must have missed him at Cross Keys.