Brendan Gallagher looks back at the players who shone on the biggest stage

Rugby World Cup has spawned many iconic moments and images and topping that list, or at least equal with the memory of Nelson Mandela in his Boks shirts in 1995 must be Siya Kolisi being presented with the Webb Ellis trophy 24 years later in Yokohama.

A black South African captain, a man born and raised in an impoverished township in Eastern Province, guiding the Boks to victory and skippering a side including six players of colour in the starting lineup and 11 in the larger squad.

This was the story, started in 1995, coming full circle. That side in 1995 had just one black player – Chester Williams – while in 2007 Bryan Habana and JP Pietersen bravely flew the flag but by 2019 South African rugby was fully integrated and seemingly free of discrimination, or as free as any sport can be of long-held prejudices. Those early pioneer players bravely helped forge the Rainbow Nation while there is a sense that Kolisi and his generation of black and coloured players are the product of that newly formed nation.

And South African rugby is much stronger as a result. The black and coloured communities had always loved their rugby even though they received precious little encouragement – indeed quite the opposite for many decades – but now South Africa was fully embracing their skills, athleticism and passion. Blend that with the old Anglo-Saxon and Boer rugby communities and you have a heady mix ready to take the world on in perpetuity.

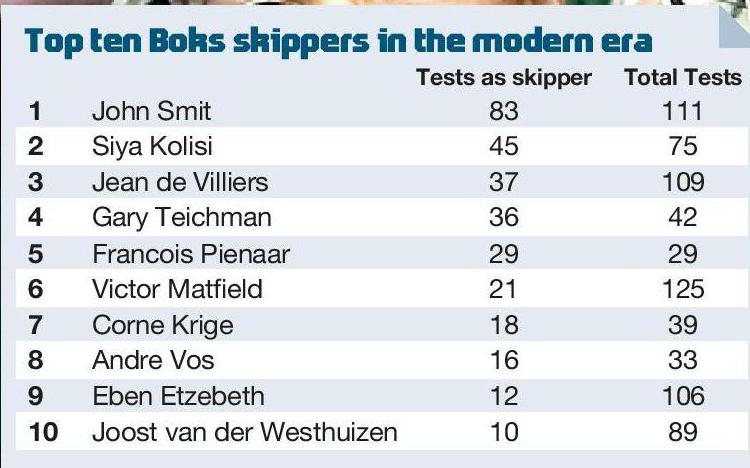

Kolisi was the understated man who made this happen, a quiet and calm hand on the tiller, a stalwart statesmanlike figure almost in the manner that Francois Pienaar was a statesman and diplomat. Both naturally think and say the right thing and represent the optimistic face of the Rainbow Nation.

Still waters run deep though with Kolisi, his serene countenance comes after a lifetime of struggle and dealing with personal issues that were largely the product of his environment. His evolution represents the reality of modern day South Africa and is worth reflecting on.

Siyamthanda – Siya for short – Kolisi was born into a chaotic household in the seething shanty township of Zwide on the north west outskirts of Port Elizabeth which has recently reverted to its Xhosa name of Gqeberha. There was rarely enough food to go around and hunger and a groaning stomach was a way of life.

His mother Pekhama was just 16 when giving birth, his father Fezakele was still at school. Pekhama was to have two other children by other partners and the young Siya witnessed much domestic abuse with his mother being beaten up by successive fathers. For much of this period the rock in his life was his grandmother Nolulamile who was eventually to die in his arms. His mother passed away in 2009 when he was 17. His experience is not unusual for post-apartheid black South Africans. Life could still be incredibly tough.

He and his mates in the township would sniff petrol to get high in the streets he witnessed murders and widespread violence – as a young boy he once stood on helplessly when a man was stoned to death in his neighbourhood – and the trauma of those years was to work through later in life when at various times he resorted to alcohol and by his own admission went through a phase when he was addicted to pornography and strip clubs. There was a heavy price to pay in the psyche of a youth experiencing the worst life could throw at him.

Like many hugely disadvantaged and frankly abused young black South Africans he could have gone off the rails – “prison or death” was the usual outcome to use his own expression – but, in an oft repeated story, he found salvation in sport and rugby in particular. He started playing township rugby as a seven-year-old and enjoyed seven years with the African Bombers, enjoying the physical release of hard, disciplined, physical combat. It was there that he chanced upon his first mentor, the club coach Eric Songwiqi.

He was a talent and, after impressing at a youth tournament in Mossel Bay, Songwiki helped Kolisi secure a scholarship at the prestigious Grey High School which is sometimes touted as the world’s most successful rugby school. They have played rugby there for over 150 years and at 1st XV level, boast a win rate of over 90 per cent during that time.

The school has spawned 45 Springboks not to mention England World Cup winner Mike Catt and the fact that the school’s 1st XV pitch is now named the Siya Kolisi Field – and the cricket pitch is the Graeme Pollock Oval – gives you some idea of the status Kolisi now enjoys.

When he arrived though, he could not speak English, not to any degree anyway, and only learned the language when he was taken under the wing of Nick Holton who became his biggest buddy and a few years later was best man at Kolisi’s wedding.

It was a struggle but a fight he won as Kolisi quickly became a schoolboy star and represented South Africa at U18 and U20 levels. He was a flanker but as usual in South Africa it’s sometimes difficult to differentiate between an openside and blindside wing forward, a process further complicated by the fact that the notional openside wears six where throughout the rest of the world it denotes a blindside flanker.

Kolisi always wears six – an openside – but has always straddled both positions. He possesses the power and strength of a traditional blindside but the dynamic athleticism and marauding instincts of an openside. He is not easy to pigeonhole and that occasionally held him back.

Take his Boks career for example. He made his senior South African debut off the bench against Scotland in 2013 – Bok number 851 – but it was three years later and a further 12 caps as a replacement before he made his first start for the national side, against Ireland in Cape Town. Versatility and reliability are great qualities but they don’t always accelerate you to prominence and stardom.

These were tricky years despite his increasing status. In 2012 he was reunited with his half-sister Liphelo and half brother Liyema who had been taken into the care system and were being fostered. The same year he met his future wife Rachel and they decided to legally adopt his siblings, a process that took 18 months. In 2014 he proposed to Rachel on a helicopter flight around Cape Town and in the same year their first born arrived.

Life was moving fast and it wasn’t always the smoothest process. He was bitterly disappointed at failing to make an impact at the 2015 World Cup – just two appearances off the bench – which sparked, by his own admission, a period of heavy drinking and feeling sorry for himself.

Rachel, who had come over with a party of wives and girlfriends, was not impressed and had her say before departing back home a week early. She urged him to take a more positive outlook on life, let the good times in and deal with the setbacks in their stride. They married in 2016 which is also when his career really took off as he nailed down a starting place in the Boks team.

Life blossomed and then came that historic moment in 2018 when Rassie Erasmus, newly appointed as South Africa’s coach, made Kolisi the Springboks captain, the first black man to captain the nation’s pride and joy. Even then some spoke of tokenism but Erasmus had seen that Kolisi was the natural leader in the new emerging group.

Yes Eben Etzebeth was injured but the world’s best lock hadn’t looked particularly at ease as skipper during the autumn tour of Europe. Your very best player isn’t always your best available captain. Pienaar was not South Africa’s best player in 1995. He was bloody good… but he wasn’t Joost van der Westhuizen or Ruben Kruger or Andre Joubert.

Time was short and South Africa had much work to do. Progress was patchy. A 2-1 series win over England in 2018; victory over the Pumas in Durban but defeat in Mendoza; a famous win over

New Zealand in Wellington but defeat in Pretoria; wins and defeats against Australia; victories at Stade de France and Murrayfield but defeats at Twickenham and the Principality Stadium. The Boks were ballpark but far from being favourites ahead of RWC2019. Cometh the hour cometh the man. South Africa, if you recall, started their campaign with a potentially dispiriting defeat against New Zealand but Kolisi, who was ever present in the tournament, had learned to take what life threw at him.

They had lost a battle but the war was still there to be won as they reeled off stress free wins over Namibia, Italy, USA and then Japan in the quarter-finals before their one tricky encounter with a nuggety Wales team in the semi-finals. Wales had won their last two games against the Boks and Kolisi and Co. had a healthy respect for them. Their pack was resilient and Wales over the years had learned how to survive on reduced rations up front.

It was desperately close and scrappy, not a game for the neutral if we are being honest, but South Africa remained cool and scraped home 19-16. It was their one poor performance of the competition, they had performed well in defeat against New Zealand, and they took heart from that and produced their very best against England in the final.

A glorious personal and collective achievement but also just a moment in time, the great fight remains and the bigger picture dominates. As Kolisi concluded in his autobiography Rise: “There’s no freedom until everyone is free, no safety till everyone is safe, and no equality until everyone is equal.”