PETER JACKSON

THE MAN TRULY IN THE KNOW

The last time Wales selected an English prop, Colin Smart of Newport, they made the mistake of taking his acceptance for granted. Having studied at Cardiff University, the Londoner had been living in Wales long enough to qualify under the three-year residency rule and had been picked not for any old Test match but the ultimate one, against the All Blacks.

As if that wasn’t enough, there was the added attraction of playing alongside a galaxy of home superstars fresh from their exploits for the Lions in South Africa that summer. Why would anyone find such an opportunity anything less than irresistible?

That Smart politely declined the invitation shows how attitudes towards playing only for the country of your birth-cum-upbringing have changed in the 49 years since the Welsh selectors, the venerated Big Five, made their not-so-Smart move in the autumn of 1974.

The man himself loved being part of a Welsh club scene, then the envy of the world. He loved it so much that he racked up more than 300 matches for Newport in ten years at Rodney Parade and has lived not far away ever since his retirement during the Eighties.

Humbled by the Welsh approach, Smart asked for a day or two to consider the implications. No matter how hard he tried to convince himself that, yes, he might be able to pass himself off as Welsh, one fact kept jolting him back to the reality of where he came from.

He was a Londoner, born and bred within earshot of the old Arsenal stadium at Highbury. Those 21st century professionals who move between the Hemispheres to find a country to play for will probably never appreciate why that mattered.

For Smart and his contemporaries, and the generations who went before them, nationality was all that mattered. Within 48 hours of being selected, Smart had ruled himself out, not because he didn’t want to play for Wales but that he couldn’t justify it for the simple reason that he had been born elsewhere. And so he declined in suitably apologetic language: “Sorry, but it has to be England or bust. I trust you will understand.”

A cynic might assume that he used the Welsh invitation as a chance to dig the England selectors between the shoulder blades and advise them to get a giddy-up. Far from rushing to dress him up in a Red Rose lest the Welsh came calling again, it took them five years during the most barren of English decades before picking him.

“I thought my chance of an England cap had gone,” Smart said. “I was tempted to play for Wales, of course I was. I love Wales and the Welsh people but I wasn’t born there. I believed then and still do now that you should play only for the country of your birth.

“It’s ludicrous for players to be allowed to hop from one country to another. While I was thinking long and hard about playing for Wales before making my decision, I had a couple of letters saying: ‘How dare you take the place of a real Welshman’.

“Then, when I made my decision, I had another couple of letters from Welsh fans saying: ‘You ungrateful b*****d’.

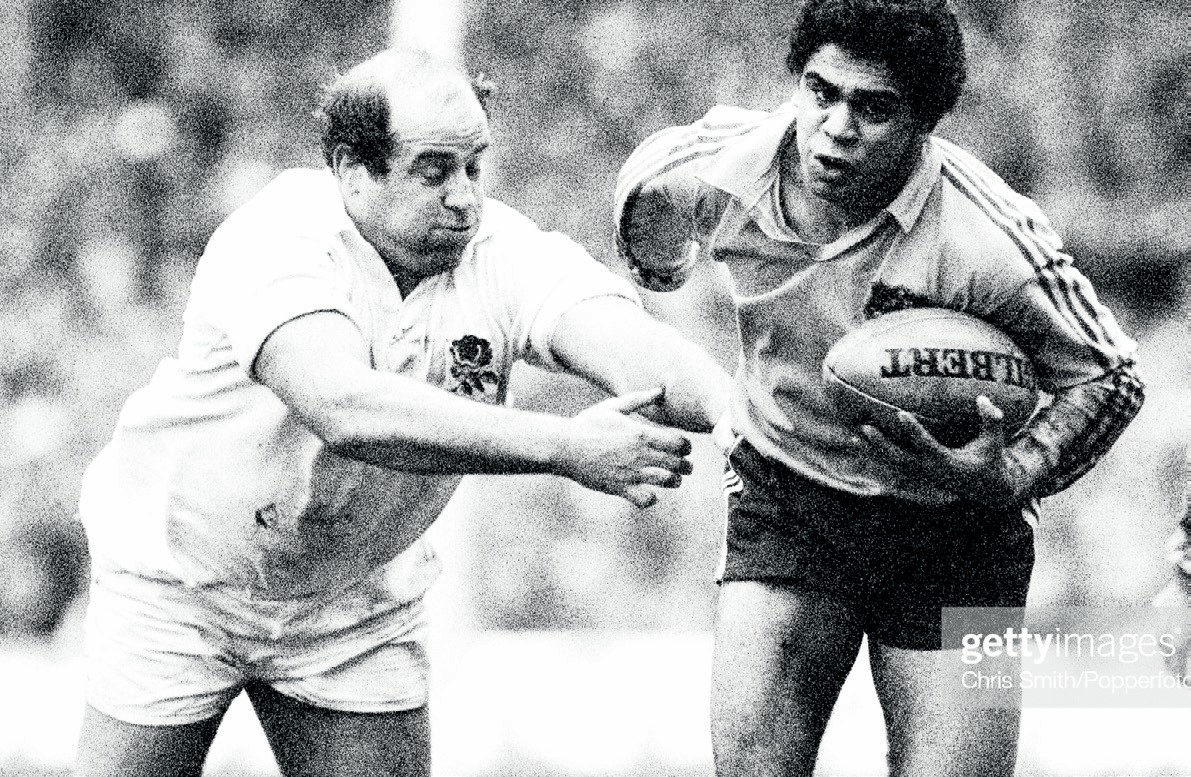

Three of his 17 internationals were against Wales: a crushing 27-3 defeat at the Arms Park in 1979, a 17-7 win at Twickenham in 1982 and a draw, 13-all, back in Cardiff the following year.

Which brings us to Henry Thomas, an English international employed in France but now en route from Montpellier to do a double which would have been unthinkable even in the earliest international era when Ireland set sail for Wales with 13 men and had to borrow a couple of players from Newport.

Thomas has played for England against Wales, at Twickenham 10 years ago. Now he is on course to play for Wales against England this summer, in Cardiff or back at HQ a few weeks before the World Cup kicks off in France.

At 31 he fits the criteria allowing him to switch allegiance with the blessing of World Rugby. One, his father, Nigel, was born in Swansea and, two, he has not played Test rugby for the last three years. In fact, Thomas has not done so for nine years which will make his gap between internationals the longest of the professional era, probably the longest since France managed without the late Pierre Dizabo from January 1950 until July 1960.

Thomas’ time on active service for England has to be measured in minutes because the sum total doesn’t add up to as long as an hour. Warren Gatland won’t give two hoots about that. What the head coach had to say on the subject hardly suggests that Thomas leapt at the chance of reinventing himself in a different cause. “He’s someone we spoke to a number of years ago about his availability,” Gatland said. “We think with his experience he brings something different.”

The World Rugby rule making it possible from the start of last year was designed to benefit Fiji, Samoa and Tonga, offering some compensation for players from all three islands discarded after a few matches for the All Blacks, in some cases as few as one.

That has enabled Charles Piutau, Israel Folau, Malakai Fekitoa and George Moala to reappear for Tonga at the World Cup along with the All Black prop Atu Moli, redundant since the thirdplace decider against Wales four years ago.

World Rugby’s failure to limit such transfers to Tier 2 nations has cleared the way for at least two of the supposed elite to help themselves. Jack Dempsey’s three-year stint as a non-playing Wallaby allowed the Australian to resurface in Scotland on the strength of a Glasgow grandparent.

Similar ancestry enabled Munster‘s utility back Ben Healy to exchange his uncapped status in Ireland for a Scotland debut, a choice which he was free to make before the most recent change to the ever more confusing nationality rules.

Such switches of allegiance are unlikely to end with Thomas’ imminent conversion from England to Wales. Having played his last match for Ireland in February 2020, Ulster scrum-half John Cooney is free to pursue his Scottish ancestry and change from green to blue.

Moral issues aside, the rule allowing such movement does nothing for certain countries who have no alternative but to grow their own, almost without exception. Why should Argentina, South Africa, Georgia and Chile be punished simply because their geographical location puts them at a disadvantage?