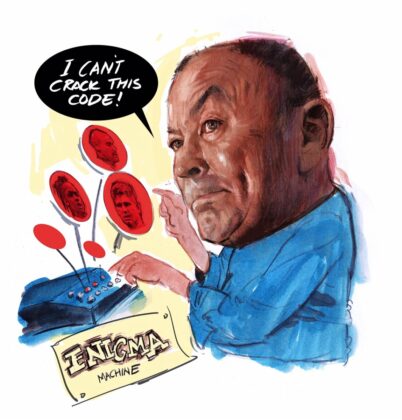

ENGLAND have become an enigma under Eddie Jones, and the signs are that the outcome at Murrayfield will not bring about an immediate change.

Enigma is the only word that describes a team that veers from one extreme to the other in the course of a year.

Consider the mood swings. Take the mind-boggling meltdown which led to the draw with Scotland almost a year ago at Twickenham as a starting point; move on to Yokohama and one of the most comprehensive dismantlings of New Zealand ever seen; wind forward a week later to the no-show against South Africa in the World Cup final at the same venue; and now press the play button on the pasting in Paris last weekend by a team of French Test novices.

My sense is that part of the reason why this England side is so hamstrung by inconsistency is that it lives in the shadow of its coach – and that while Eddie Jones may not be the biggest physical specimen, he is a forceful character who casts a long shadow.

Jones is overprotective, in the sense that while he says he encourages the England players to think on their feet and show leadership, he rules the roost and annexes responsibility for almost everything.

The most glaring example is when he gets into stuck-record mode in terms of taking responsibility when England play poorly.

Jones instantly holds up his hands and says mea culpa, usually followed by the catch-all that he did not prepare the team as well as he should have. This happened again when the head coach said he was at fault for the training camp in Portugal which left England underprepared for the French game.

The problem is that usually there is not much of an appendix, with very few details forthcoming about how and why the shortfall occurred.

While we all understand that the buck stops with the head coach, and that slagging-off players publicly is not going to reinforce team harmony or trust, there are times when this view that professional players must be protected from criticism at all costs becomes counter-productive.

At Press conferences it is Jones who holds court – Fast Eddie ready with the quips, the jibes, the thrust, the counter-thrust. This means that very often his captains, whether Owen Farrell, or Dylan Hartley before him, might just as well be cardboard cutouts.

A prime example is that we heard precious little from Farrell about what, in his view, went wrong in Paris, or, for that matter, on why England were on the receiving end of such a hammering by the Springboks that their dreams of winning the Webb Ellis trophy disappeared without trace.

What we could see in both instances was that leadership on the field was lacking, and the body language throughout the team was light-years from the bristling collective competitiveness Jones had forecast.

A look back at the World Cup final tape shows that as soon as Kyle Sinckler is injured key England players have the rabbit-in-the-headlights look of those who have seen Plan A smoked, and have no idea of how to implement Plan B as the Springbok panzers rumble towards them.

There was no sign of Farrell and his backline generals, George Ford and Ben Youngs, or any of the senior forwards, taking the initiative. Instead, they were waiting for instructions from the Jones command module – and all we can deduce is that either Jones had no Plan B, or that captain Farrell and his leadership group could not put it into practice in the 78 minutes after Sinckler was helped off.

There were similarities in Paris. England started badly, and looked as if they were spooked by Jones’ pre-match boast that they would bring a “brutality” that would leave the callow French battered.

The England forwards were tentative, to put it kindly, with most of them – with the exception of Courtney Lawes – lacking the drive and technique to win the gain-line contact. Instead, it took Ellis Genge’s arrival in the second half for us to see anything close to the controlled aggression Jones had predicted.

The only thing about England that was brutal was the contrast between Genge and the rest of the pack.

This brings us to selection, a crucial area where Jones has proved to be the enigma. In his recent book he admitted he should probably have picked Joe Marler and Henry Slade in his World Cup final starting line-up ahead of Mako Vunipola and Ford.

That apart, acknowledgements by Jones of mistakes in selection are rare. Yet, if, as he has claimed, his radar as a Test selector is almost flawless, how does he explain the anomalies as he goes into his fifth year as England coach?

The most recent of these is moving Elliot Daly back to the wing, after an experiment lasting almost two years at full-back. This has coincided with the rapid promotion of George Furbank, who won his first cap at 15 against France despite being in his first full season in the Northampton first team, and the discarding of Ruaridh McConnochie, who was included in the 2019 World Cup squad after being touted by Jones as the next bright young thing at full-back.

Then there is Jones’ refusal to bring a promising No.8 like Alex Dombrandt – who has more Premiership mileage under his wheels than Furbank – into his training squad as a powerhouse alternative to Billy Vunipola. This gives legs to the rumour that the more others champion a selection the more the coach sets his face against it, because, rather than considering it purely on its merits, he sees it as bowing to the baying mob.

And what about the stasis in selection at scrum-half, with Jones giving Youngs the chance to monopolise the position during most of his tenure, while offering virtually no encouragement to rivals like Ben Spencer and Dan Robson. The vacuum in the position now that he has demoted Youngs to the bench is entirely of the coach’s making.

Enigmatic England are a mirror image of their coach. So far, Jones has not yet been as successful as the World War 2 boffins at Bletchley Park in managing to crack his own enigma code, and, until he does, sustained success will remain elusive.

NICK CAIN