Bernard Lapasset has been waxing lyrical about the fantastic growth in the popularity of Sevens this week. That this popularity has as much to do with the carnival atmosphere surrounding the sport – an unrivalled opportunity for modern ‘eventers’ to have a giant party and for regional or city governments to cash in and boost their tourist business – as it has with genuine support for the abbreviated game, seems not to have registered with the IRB’s French chairman.

Bernard Lapasset has been waxing lyrical about the fantastic growth in the popularity of Sevens this week. That this popularity has as much to do with the carnival atmosphere surrounding the sport – an unrivalled opportunity for modern ‘eventers’ to have a giant party and for regional or city governments to cash in and boost their tourist business – as it has with genuine support for the abbreviated game, seems not to have registered with the IRB’s French chairman.

What pleased Lapasset so much was that there had been tenders from 17 Unions around the world to host a round on the World Series circuit in 2015-16.

The fact that eight of the 17 are already established World Series venues, and that most of the others have traditionally staged Sevens tournaments, took some of the gloss off the IRB spin that this represented an explosion in interest in sevens.

What is of greater concern is the way that the IRB are coming out with half baked PR fanfares while, at the same time, failing to manage Sevens following its admission to the 2016 Olympics in Rio.

I have always been a keen supporter of Sevens, but, as advocated in this column previously, believe that its development should be worked out in tandem with that of the 15-a-side game, rather than it becoming a separate entity.

The warning that, in the absence of a strong IRB strategic plan ahead of the Olympic Sevens in Rio, the abbreviated code could end up as an unwanted rival to the 15-a-side game, prompting friction between the two, is now in danger of becoming a reality.

By relaxing residency regulations to an absurd degree, presenting players with a loophole to play for a second country as long as there has been an 18-month gap, the IRB are creating a special, separate playing field for Sevens.

As reported in The Rugby Paper last weekend this could enable Steffon Armitage to play for France, while former New Zealand Test wings, Joe Rokocoko and Sitiveni Sivivatu, could appear for Fiji.

Taken to its logical conclusion, it is therefore only a matter of time, it is argued, before there is a precedent for the same 18-month rule to apply in the 15-a-side game, as both games are Rugby Union and played under the aegis of the IRB.

This raises the absurd spectre that you could be playing for one country one year and, if dropped, could swap allegiance and be playing for another country the following season.

This licence to nation-hop has been compounded by the IRB’s decision to extend Regulation 9, which governs international player release, to include next season’s nine World Series tournaments.

In a nutshell, on top of the international player release windows existing already in the 15-a-side game, this allows national Sevens coaches around the world to demand the release of players from their club contracts for a further nine weeks, i.e. for the week leading up to and including each tournament.

The implications are serious for clubs in the Premiership and the Top14 in France, leagues in which promotion and relegation is enshrined.

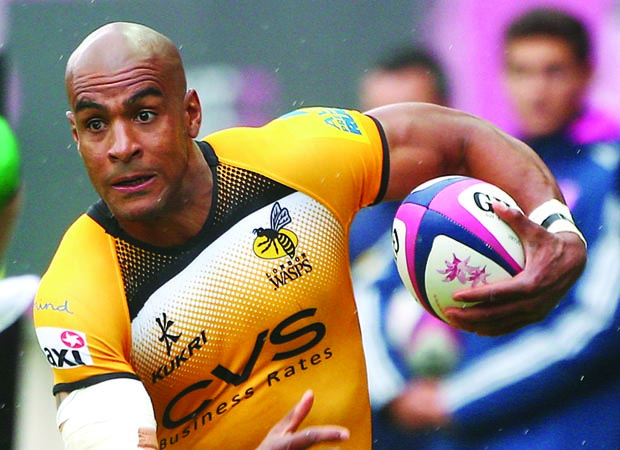

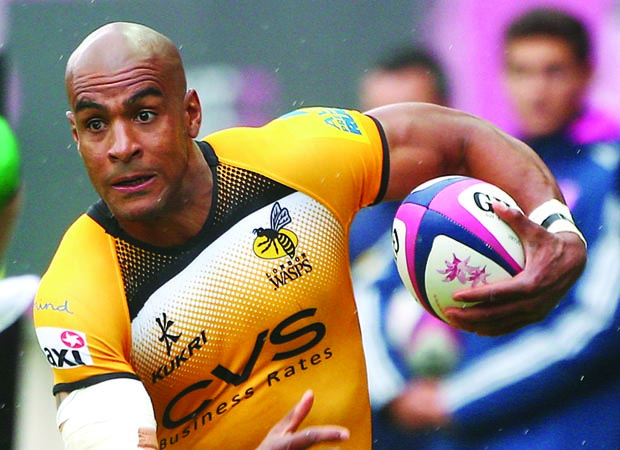

For instance, a club like Wasps would be in danger of losing their two best wings, Tom Varndell and Christian Wade, should the England Sevens coach, Simon Amor, select them. Given the implications that has for the competitiveness of the Premiership it puts the IRB, once more, on a collision course with the European clubs – and already Leicester’s chief executive, Simon Cohen, has warned of repercussions.

Ultimately, it is a conflict that the IRB are unlikely to win because the clubs, as the main paymasters of players, will probably instruct any player that they do not want to lose to the Sevens circuit to discover an injury at the appropriate time.

The Sevens structure is also in a dreadful tangle because the IRB have failed to persuade the IOC to drop their convoluted and non-meritocratic qualifying system in favour of simply using the World Series as the qualifying tournament.

At the moment Great Britain can qualify if a national team nominated as the GB representative – say, England – finish in the top four of the World Series.

However, if England were to finish fifth, and Wales fourth, because the Welsh were not the nominated team, GB would then have to select a scratch side to play in the European qualifying tournament – pitting them against France for the sole qualifying place.

Should GB negotiate this qualification maze and eventually make it to Rio in 2016, they might finally be in a position to select a Lions-style squad the best of English, Welsh and Scots competing for gold.

However, from this distance, instead of being one of the favourites, GB are heavily handicapped already.

*This article was first published in The Rugby Paper on July 6.