Talk about synchronicity. When confirmation of Jonny Wilkinson’s much-touted retirement was filtering through this week I was actually rummaging around my garage looking for a much treasured, so annoyingly lost, VHS video of the England Schools putting Australia Schools to the sword Down Under in 1997 when they won 38-20.

Talk about synchronicity. When confirmation of Jonny Wilkinson’s much-touted retirement was filtering through this week I was actually rummaging around my garage looking for a much treasured, so annoyingly lost, VHS video of the England Schools putting Australia Schools to the sword Down Under in 1997 when they won 38-20.

I’d been searching for it, on and off, since a house move 18 months ago in the sure knowledge that one day soon its footage would be worth revisiting. Now was that day.

With renewed purpose I ripped through box after unpacked box until suddenly there it was, hiding under the August 2000 Rugby World magazine from which a fresh-faced Steve Borthwick smiled beatifically, his nose unbroken, his face unscarred.

I popped the video in the player and settled down for a treat. The class of ’97 was the strongest, most star-studded, England Schools team in history and their tour of Australia that year, at the very dawn of professionalism, launched any number of notable Test and club careers.

Andrew Sheridan, Lee Mears, David Flatman, Borthwick, the Sanderson brothers, Andy Beattie, Mike Tindall, Simon Danielli, Lee Best, Iain Balshaw, Tom May, Simon Amor . .. and a certain JP Wilkinson, of Lord Wandsworth School, Hampshire.

There he was 17 summers ago, his face full of anxious concentration and focus. The smallest kid on the field putting in the biggest hits, a cruiserweight happily engaging, and getting the better, of the dreadnoughts in the Australian pack.

Wilkinson was playing centre that day alongside an Adonis-like figure with a mop of a blond hair – the young Tindall – because in those early days he was not regarded as England’s first choice fly-half. That honour befell Sedbergh’s James Lofthouse, the England captain but one of the few from that tour party to disappear into obscurity.

Lofthouse, a more than decent player who fell off the radar after a spell at Worcester, had been injured during the schools’ Five Nations when Jonny deputised and the first sign that somebody special was moving among us became evident down at Narberth RFC on April 12, 1997.

England Schools, despite their stellar line-up, were, as ever, having the greatest difficulty in despatching the Welsh to claim a Grand Slam. Deep into injury time England were trailing 17-15 and instinctively you looked around to see who was rallying England. Who wanted it the most? Wilkinson, the smallest bloke on view, was standing tall issuing instructions, demanding the ball and insisting that England could still win this.

England’s forwards rumbled right and then left before he smashed over a 35-yard left-footed dropped goal before promptly waving away colleagues and sprinting back to his half in case there was time for a restart. A man among boys even though he looked the youngest on the pitch.

Nobody in the history of rugby has worked harder at his game than Jonny Wilkinson yet, ironically, nobody has changed less as a player. I’m struggling to think of any department in which his game changed fundamentally since that day in Narberth and the Aussie tour soon after.

Jonny could always kick magnificently and tackle heroically. He could always pass deftly and, although always capable of making a half-break with a jink, he never possessed the blinding speed to ram that home and therefore had to perfect his offloading game from an early age.

Wilkinson’s career-long challenge was to harness his intensity, maximise those talents every time he walked on the pitch, to maintain an extraordinary levels of fitness in the face of potentially crippling injuries and to learn how to live with a level of fame no rugby player in England had ever experienced and, even now, probably only Jonah Lomu can truly relate to on a worldwide scale.

That’s why the most influential figure in Jonny’s career, apart from his wonderfully supportive parents, was Steve Black who makes no claims whatsoever as a rugby coach but is the shrewdest of lifestyle gurus and brain mechanics.

When Jonny arrived in international rugby in 1999 he was essentially the finished article and, if the older hands had looked to him in the last minute of added time against Wales at Wembley that March, England might well have claimed the Grand Slam.

Instead Mike Catt, a great player but no dropped goal specialist, sliced wide and a golden opportunity was lost. England and Clive Woodward, although promoting Wilkinson at the earliest possible opportunity to starting duties, were still not quite sure just how good he was. Nobody was.

Wilkinson’s maturity and sense of duty was manifest right from the start. The Sunday before that Wales game I trooped off to his parents’ house in Farnham to ghost his newspaper column with a sense of foreboding. He had taken a hellish smack in the face the previous afternoon playing for Newcastle at Richmond and there seemed no way he could start against Wales. This was going to be a futile exercise.

When I arrived he was laying down in a darkened room clutching an ice pack to the nastiest black eye – swollen grotesquely and fully closed – that I had ever seen. Despite protestations to the contrary he was clearly in considerable pain yet somehow managed to get through a 30-minute interview without losing consciousness.

He even tried to rise and make a cup of coffee at one stage although his Dad, Phil, intervened and ordered him to stay on the couch. I was flabbergasted to both see his name on the team sheet two days’ later and then to watch him line up at Wembley. Nothing was going to stop him and in the depths of his injury misery in the mid-Noughties, when many were writing him off, I often reflected on that image. He would rise again, no question. Put your life on it.

Later that autumn, during the 1999 World Cup, that determination and focus was again evident, albeit in rather unusual circumstances. I thought he had excelled against Fiji in that curious quarter-final play-off game at Twickenham – 23 points and an increasingly authoritative performance – but Woodward dropped him for the quarter-final in Paris against the Boks. He was gutted but another column loomed and en route to Paris the following day he tried to phone me at the pre-arranged time from the Eurostar.

Six times he phoned, six times we got cut off. Eventually an hour later, at the seventh attempt, we managed to get a decent line for ten minutes. I know of precious few sportsmen who would have gone to that trouble at such a moment of disappointment. Jonny had started so he would finish. There was a task to perform, an obligation to fulfil. It was then I realised his on and off the field persona were identical.

That 1999 World Cup might have ended in disappointment but Jonny was on his way, his senior career with England rapidly gathered pace. He will always be remembered for his astonishing goal-kicking but in those seasons leading into the 2003 World Cup, England played some wondrous rugby and Jonny contributed fully to that as well.

He knew when to lean on the more experienced Will Greenwood and Catt outside him while those big miss-passes he perfected often opened up much-needed space for England’s wide men. He could cut the occasional dash himself and modern-day Twickenham has seen few better tries than his chip-and-chase effort against New Zealand in 2002.

And always the tackling. No fly-half had tackled like Jonny. In fact very few flankers have even tackled like Jonny.

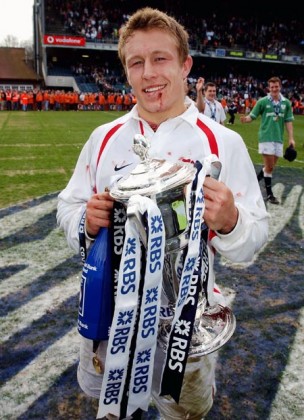

Some still argue that he wasn’t at his very best at the 2003 World Cup and there is a grain of truth in that argument. England generally weren’t quite at their extraordinary best, that was produced during their imperious Six Nations Grand Slam and those remarkable summer tour wins in New Zealand and Australia. As a team they were just fractionally over the hump but they were still good enough to hang on and win the World Cup. That’s how good England had become. When push came to shove, though, who was it who kicked all his goals in the knockout stages against Wales, France and Australia when, with the weight of a nation on his shoulders, he accumulated 62 points?

Who was inspiring colleagues with his thundering tackles and who had the bottle to do what needed doing with less than a minute on the clock in the final after missing three previous dropped goal attempts? There is a very good reason why Jonny was, and remains, English rugby’s all-time darling.

Then came the dark years, an injury list normally only associated with war. It became painful to write about, so God only knows how he coped, and it was during this introspective period he, understandably, seemed to over-analyse and answered relatively simple questions with meandering answers that, when transcribed, made no sense.

Because he was Jonny, the rugby world, via the media, demanded constant updates and ‘insight’ but frankly he just wanted to disappear out of view and only re-emerge when fully healed. He was never allowed that luxury and for a while his life became one endless medical bulletin. It was a difficult period for the most reluctant of patients.

Miraculously there were fleeting windows of match fitness which saw him tour with the 2005 Lions and contribute massively to England’s 2007 World Cup campaign when they surprised many and reached the final. But generally it was a struggle, mental and physical, and relief only really came when he moved to Toulon in 2009, the best single decision of his career, and indeed life.

At the time, though, you still feared just a tad for him. I recall one haunting Jonny sound-bite as he departed these shores: “I’ve been searching for tranquility in a world created by obsessive thoughts,” he mused but it has all worked out wonderfully.

Typically he became fluent in French before he even signed and in Toulon he discovered a heaven-sent end of career challenge to re-energise and regenerate his battered body. Wilkinson’s four seasons there have been blissfully, relatively injury-free, just the normal wear and tear you have to expect when playing elite level rugby over the age of 30.

Owner Mourad Boudjellal fully understands his worth as an iconic leader for the club and city while coach Bernard Laporte absolutely reveres him as a player as befits a former France coach who suffered so frequently against a Wilkinson-inspired England.

Toulon’s expensively gathered band of itinerants and galacticos also have total respect for Wilkinson. You can sign every player under the sun and offer them pocketfuls of gold but it takes much more than that to build a team and esprit de corps and to make a hard-nosed city like Toulon fall back in love with rugby. They needed a leader and although he never got to captain England – Woodward appointed him but injuries intervened – Wilkinson has assumed that mantle with Toulon.

His commitment to the club and region has been inspiring. His dedication to training has not lessened one iota – even a model pro like Matt Giteau happily admits that in the autumn of his own career he has raised his standards under Jonny’s influence – but Wilkinson has also taken time to occasionally smell the roses and that, too, has prolonged his career.

He flirts with Buddhism while the soothing Mediterranean air and marriage to Shelley has visibly relaxed him. Life is good, in fact, bloody marvellous.

Jonny could have retired at the end of last season but, come the moment, he was having so much fun that he signed on for another season. There was still unfinished work to be done at Stade Felix Mayol.

The Heineken Cup was in the bag, and that was fantastic, but what Toulon crave above all else is another French club championship with the last of their three titles coming 22 years ago.

The stage is set for Saturday’s game against Castres in Paris although after losing to the same opponents last year a fairytale ending cannot be guaranteed.

Of course it can’t, but whatever the result you fancy Jonny Wilkinson has finally found tranquility in a world created by obsessive thoughts.

A remarkable sporting journey is nearly over.

Pingback: jarisakti